Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

Las Casas and Indian freedom

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

BARTOLOME DE LAS CASAS AND INDIAN FREEDOM

|

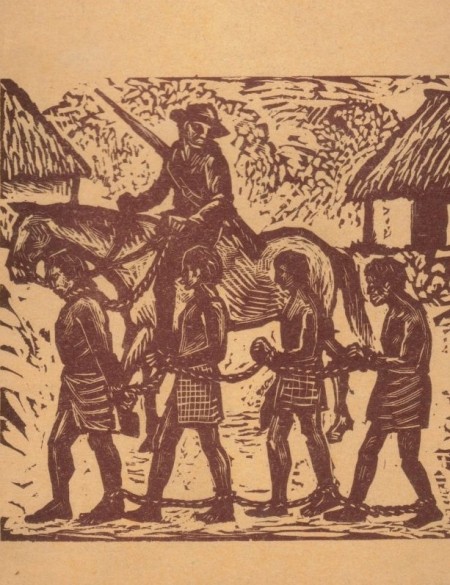

Maya Indians prisoners, in Ermilio Abreu Gómez, La Conjura de Xinum, Editorial Macehual, 1977

LAS CASAS' TREATISE ON THE SLAVERY OF THE INDIANS (1552)

Bartolomé de Las Casas resigned his office of bishop of Chiapas in 1547 and returned to Spain. Then he entered upon the most fruitful period of his life. He became an influential figure at court and at the Council of the Indies. In 1550 he came into conflict with Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, who was attempting to gain the right to publish a book approving war against the Indians (“Democrates secundus, Concerning the Just Cause of the War Against the Indians”), in accordance with Aristotelian principles. Las Casas appeared at a debate before the Council of Valladolid, where he spoke for five days straight. He influenced the committee not to approve his opponent's book for publication.

In

1552, Las Casas published several treatises to leave in written form his

principal arguments in defense of the American Indian:

"Brevisima Relación de la Destrucción de Las Indias" (A

Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

),

"Octavo remedio" (The Eighth Remedy),

"Disputa o controversia entre el obispo Don Fray Bartolomé de Las

Casas... y el doctor Ginés de Sepúlveda",

(In Defense of the Indians: The Defense of the Most Reverend Lord, Don Fray

Bartolomé de Las Casas),

"Confesionario"

(Rules for the Confessors of Spaniards who have charge of Indians),

"Tratado

comprobatorio del Imperio Soberano... que los Reyes de Castilla y León

tienen sobre las Indias" (Comprobatory

Treatise on the Imperial Sovereignty and Universal Jurisdiction which the

Kings of Castile Have over these Indies), and the treatise

"Sobre la materia de los Indios que se

han hecho esclavos",

(Treatise written at the instance of the Royal Council on the slavery of the

Indians).

From Chiapas to Panama, Indians were branded as chattels with little regard for the royal legislation that limited the practice. Two types of Indians could be legally enslaved: 1) esclavos de Guerra, or those who persisted in resisting Spanish dominion by resort to arms; and 2) esclavos de rescate, or those who had been slaves in their own native societies. But the ways in which these qualifications could be circumvented were legion, and the enterprising slave trader continued to practice his evil with little interference.

BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS

TREATISE

WRITTEN AT THE INSTANCE OF THE ROYAL COUNCIL

ON THE SLAVERY OF THE INDIANS

(1552)

"Argumento (preface) to the following treaty.

The bishop of Ciudad Real de Chiapa, Fray Bartolome de Las Casas, was pressing persistently the royal council of the Indies to consider the liberty of the Indians as the only general remedy for the Indies; and one of his petitions was, that the Indians held by the Spaniards as legal slaves, should all be given their freedom, arguing that out of their countless number not one had been enslaved justly, but that, on the contrary, all had been enslaved unjustly and iniquitously. The council having decided to set aside their other numberless occupations, and to take up this subject, charged and commissioned the said bishop to put in writing his opinions on the matter. In virtue of said royal commission and command the following proposition with its three corollaries, which like three branches of one tree, are the necessary consequences of its truth, has been established and proved. Herein is demonstrated with what justice the Indians of that New World could have been and were enslaved, and that their masters are bound to restitution."

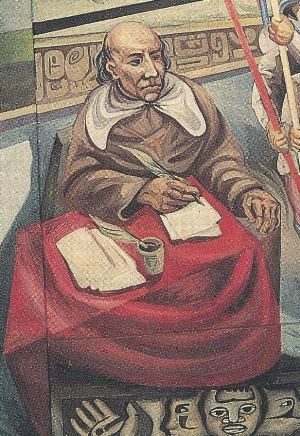

Bartolomé de las Casas, as a bishop, and Saint James, Museo de los Altos de Chiapas, San Cristóbal de Las Casas

Every Spaniard suspects the justice of the slave traffic

"Look at every Indian the Spaniards held as a slave in the New World, at least in New Spain, and in New Galicia, in the Kingdom of Guatemala, in the province of Chiapas, in the Kingdom of the Yucatan, in the provinces of Honduras and in Nicaragua, in every other area where slaves were brought from the areas cited, or acquired from others Indians, taken as taxes or as tribute, or as merchandise –leave out of consideration the Spaniards who knew what they did, we know for sure they sinned mortally- the rest suspected surely, or felt pressure to suspect the justice of their slave traffic." [...]

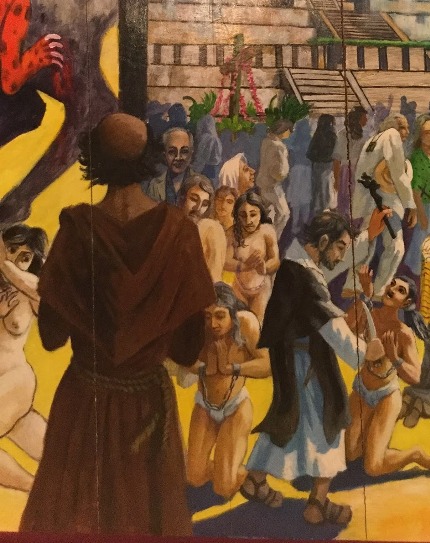

Don Vasco de Quiroga and Indian slaves, Pátzcuaro, Casa de los once patios, mural by José Luis Soto González (1979)

The Spaniards own Indian slaves ín bad conscience.

"The Spaniards who own Indian slaves, who were bought as slaves or given as barter, or given as tribute, or as gifts, or had from other Indian in any other way, these Spaniards got them knowing that they were enslaved mostly in violation of justice, of the divine and natural law, or there was a doubt, or there had to be a doubt. Therefore Spaniards who own Indian slaves gotten from Indians themselves own those slaves in bad conscience.

"The major premise of the argument is clear and no one doubts the first part of it about someone who knows. Since the one from whom the present owner received the goods had no legitimate rights to the goods, he could not transfer ownership, nor make a gift of it, nor sell it to anyone else. The reasoning is that no one can transfer more of a right to a thing than the right he has, and if he has no right to a thing, he can transfer no right at all to it. A man who knows that the goods he gets are not owned by the one who gives or sells them, the man who buys them or accepts them knowingly, becomes as evil as the one from whom he gets them; if the goods are stolen, he becomes a thief; stolen violently, he becomes a thug; run down the list of vices. That man is an owner in bad conscience.

"The reason is he is a thief and is in a state of mortal sin while he keeps hold of someone else’s goods against the owner’s will. And there is always thievery in delay. Even if the goods pass through a thousand people, they are all owners in bad conscience, as much as the first. Whoever has his hands on such goods is obliged to restitution. He is not freed from bad conscience nor from being an owner in bad faith because some laws or statute says whatever he buys on the open market he truly owns.

"The reason is that human law cannot abrogate the divine or natural law, nor work against civilized behaviour which forbids theft or the possession and retention of another’s goods against his will. The lesser authority, the king on earth, cannot set a law against the law of God who is greater than all. In laws made by lesser powers, the laws of superior powers are always understood to remain in force. The obligation to restitution is clear from a law already cited. And restitution of profits made on stolen goods, as required by the same law. The bad faith owner cannot demand back the price he paid for the stolen goods, even if law or statute should permite the opposite. The reason is the same, it is against civilized behaviour." [...]

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, 2023, August, meeting of Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (Frayba)

The Indians were unjustly enslaved

"When Spaniards bought and held slaves, they knew the slaves were unjustly enslaved, or they suspected, or they simply had to suspect, which amounts to the same. The proofs runs thusly: every Indian slave the Spaniards had from Indian masters was gotten through levies they were forced to pay, what with the litany of cruel and inhuman treatment visited on them, or gotten through the variety of deceits, unheard of, unjust, wicked deceits described earlier in the proofs of the first part of the conclusion. No human being who looked at the evidence would deny that the slaves were given and gotten unjustly and both giver and getter knew it.

"Thus the present holders of slaves are in bad conscience. They either bought them from Indians or got them through exchange – the Spaniards call it that. They used much the same methods either way. They coerced the leaders, the elders, to sell them slaves or swap them some by threatening to accuse the leaders, the elders, of idolatry –before they ever thought of being Christian- to charge them in court with adoring and sacrificing to idols. And since the chiefs did not have a many legitimate slaves as the robber Spaniard demand [...] the chiefs gave them free people from the villages. [...]

"The situation was so lawless, so rotten –and everyone knew it- like a ruckus, it had come to Your Majesty’s attention. And you had to send notice that in no way would you condone anymore the swapping. There were some chiefs, some Indians who sold themselves into slavery of their own will. But it is certain that they were few who did so. But buyers knew the sale was suspicious, and if they didn’t they ought to have, and therefore their traffic is slaves before examining the facts of enslavement closely makes them, then and now, owners in bad faith. They took, they take slaves, they held, they hold slaves in bad conscience.

"The conclusion is certain. The Spaniards knew that a huge number of Indians had been unjustly and wickedly enslaves, and that those who might have been enslaved justly were so few, so difficult to single out they could not be known for sure. Therefore the Spaniards had to cease from this traffic until they could be sure the slaves were justly enslaved. No one can put their soul in danger of hellfire for the sake of some worldly gain. [...]"

The friars release Indian slaves (mural by Miguel Angel Polanco, Museo Nacional de Antropología, San Salvador, 2011)

To be a slave of the Spaniards is life in hell

"It is not at all the same thing to be a slave of the Indians or a slave of the Spaniards. We proved that in the second premise. To be an Indian and a slave among Indians is to have a freedom a little less than the freedom of sons in the household. The life a slave leads under his owners, the treatment he receives, is gentle and kind. The life of a slave under the Spaniards is life in hell, there is no relief to it, no stop to it, no time to catch a breath from it. The standard treatment is durance vile, and at the end of a difference between being an Indian slave to Indians, and an Indian slave to Spaniards, and given that the Indian-to-Indian enslavement is according to law and custom, just ones in this case, and thus valid in matters of slavery and freedom, it is clear, from both givens, that Indian owners cannot hand over to the Spaniards greater rights over slaves than they themselves have.

"If the Spaniards use the Indians slaves given them by Indians with such uncontrolled cruelty –even if they knew for sure the slaves were gotten in a just war originally- that the end result of this bestial servitude is certain death, then it is absolutely clear the whole thing is robbery and the Spaniards must make restitution. It is beyond measure, the cruelty the Spaniards inflict constantly on their slaves, they destroy them this way utterly.

Juan O' Gorman, Retablo de la Independencia de México, 1960, Museo Nacional de Historia, Castillo de Chapultepec, México

"We know from experience that no law, no argument, no rule would be enough to make the Spaniards moderate the harsh treatment they habitually mete out to their slaves, so they would not use more power over them than did the Indians who handed them over. Therefore, when someone is discovered among the Indians to be a slave legitimately, he should not to be left in the hands of a Spaniard, not with any justice. It is rather the judgment of good men that the Indian should grant him only that right which the seller or giver had and could sell or give, separating him carefully from all that excess which the owner has no right or power to demand from him unless unlawfully.

"When the master of a household denies the necessary food to a legitimate slave, denies it so there is no escape in a time of sickness, so that the slave is doomed, from that moment on, according to human laws, the slave regains his freedom completely. How much more reason there is for the Spaniards to lose his right to the little service the Indian who spoke of owes him? And for the slave to be freed from a great evil? He would perish inexorably in that terrible state. A lesser evil is the one we describe, i.e., the legitimate slave should pay the owner in other ways, and the slave should begin to know what freedom is. [...]"

(Bartolomé de Las Casas, Tratado sobre la materia de los indios que se han hecho esclavos, 1552, translated by Francis Patrick Sullivan)

Look at the page:

"Las Casas against the conquistadores"

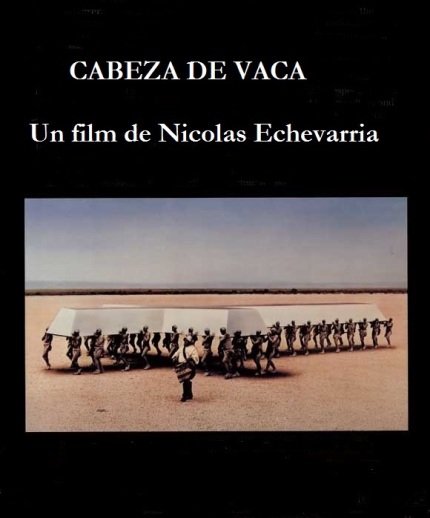

Indian slaves carrying a gigantic cross; last sequence of the mexican movie "Cabeza de Vaca", 1990

Letter from Bartolomé de Las Casas to Prince Philip (afterwards Philip II)

"In this city [...] there is a large number of Indians held unjustly as slaves; they kept many Indians imprisoned after the order was given for their release, some being hidden and others taken into the country and elsewhere. I have even been told by a man who knows—to clear his conscience—that there was a great deal of bribery and corruption among wicked people, who used three or four or ten ducats to outrage God, stealing the liberty of the Indians and thus leaving many in perpetual slavery: they also hid the truth by threatening the Indians who showed themselves and by other means [...]

They are daily treated worse and worse by those who call them slaves and dogs. [...] I have seen what I state ever since I came here. Your Highness would both laugh at and abominate the spice dealers of this city, who barter spices for Indians and for gold (as it is they who mostly own them), and their fierceness in making war on the Indians, that makes them to seem like dummy lions, painted. What I wish Your Highness would do to protect all such Indians as are left neither slaves or freemen and all who are bound in any way, would be to oblige their owners to exhibit a receipt of the sale: because it is clear to every one, save to those whose perceptions God has allowed to be weakened by their malice, audacity, and ambition, that there has never been a war in all the Indies for which there was any real authority given by His Majesty or by his royal predecessors. The royal instructions on this point have never been heeded, as I have seen and on my conscience affirm, and as all those violaters admit.

Consequently, as there was never just cause, it follows that all the wars were unjust and that no Indians could have been justly enslaved: all the more so since the Spaniards attacked them intime of peace and captured millions of them. This being thereal truth, Your Highness should order that all such owners be obliged to prove the title of him who sold any such Indian, and soon back till the first one who stole or treacherously captured him is unearthed. In the meantime the Indians should be taken from them and placed as above indicated, all of which should be done within a limited time, so that the legal proceedings would not last eternally; and when they are finished the said Indian should be declared free."

(Fray Bartholomew de Las Casas, Bishop of Chiapa, 20 th april 1544)

Mexican heros, Benito Juarez and Bartolomé de Las Casas, painted on chairs (Casa de los Venados, Valladolid, Yucatán)

Bartolomé de Las Casas: Confesionario (1552)

"Fourth, if the penitent holds any Indians as slaves, by whatever way, title, or manner he might possess them, then immediately and at once he is to grant them irrevocable freedom, without any limitation or condition. Also, he is to ask pardon for the injury he did to them in making them slaves, usurping their liberty, or in helping, or in being part of whatever might have been done; or if he did not make them [slaves], [he is to ask pardon] for having purchased, possessed and served himself with them in bad faith. For this much is certain, and the confessor must know it, there is no Spaniard in the Indies who acted in good faith, concerning four things: the first concerns the wars of conquest; the second concerns the fleets that were assembled for the Islands in Tierra Firme in order to bring assaults and robberies to the Indians; the third concerns the enslaving and buying of Indians that had been sold as slaves; the fourth concerns the carrying and selling of arms and merchandise for the tyrant conquistadors, when they were actually engaged in the conquest, violence and tyranny mentioned above. Thus it shall be ordained that repayment be made to these Indians for what the penitent gained through their enslavement, for each month or each year, all that the discrete confessor might judge to be fitting recompense in light of their work and service and the injury done to them."

(Confesionario: Avisos y Reglas Para Confesores, by Bartolomé de Las Casas, A Translation by David Thomas Orique, O.P.)

Bartolome de las Casas and Indian slaves, Trinidad, Cuba

Motolinia, Franciscan friar opposed to Bartolome de las Casas:

"After what I said above, I saw and read a treatise that Las Casas composed on the subject of the Indians enslaved here in New Spain and on the islands, and another one concerning the opinion he rendered on putting the Indians in encomiendas. He says that he composed the first on commission of the Council of the Indies, and the second by your majesty’s order. No human being of whatever nation, law or status could read them without feeling abhorrence and mortal hate and considering all the residents of New Spain as the most cruel, abominable and detestable people there are under the sun. This is the effect of writings that are done without charity, that proceed from a spirit alien to all piety and humanity. […] May God pardon Las Casas for so gravely dishonoring and defaming, so terribly insulting and affronting these communities and the Spanish nation, its prince, councils, and all those who administer justice in your majesty’name in these realms."

(Fray Toribio de Motolinia, to the emperor, from Tlaxcala, 2nd of January, 1555. In James Lockhart and Enrique Otte, Letters and people of the Spanish Indies, Cambridge University Press, 1976)

Mexico city, Motolinia's street

Matías de Paz, Bartolomé de Las Casas' precursor.

"Whether Our Most Christian King may govern these Indians despotically or tyrannically.

"Answer: It is not just for Christian Princes to make war on infidels because of a desire to dominate or for their wealth, but only to spread the faith. Therefore, if the inhabitants of those lands never before Christianized wish to listen to and receive the faith, Christian Princes may not invade their territory. Likewise, it is very convenient that these infidels be requested to embrace the faith.

"2. Whether the King may exercise over them political dominion.

"Answer: If an invitation to accept Christianity has not been made, the infidels may justly defend themselves even though the King, moved by Christian zeal and supported by papal authority, has waged just war. Such infidels may not be held as slaves unless they pertinaciously deny obedience to the prince or refuse to accept Christianity.

"3. Whether those who have required heavy personal services of these Indians, treating them like slaves, are obliged to make restitution.

"Answer: Only by authorization of the Pope will it be lawful for the King to govern these Indians politically and annex them forever to his crown. Therefore those who have oppressed them despotically after they were converted must make appropriate restitution. Once they are converted, it will be lawful, as is the case in all political rule, to require some services from them -even greater services than are exacted from Christians in Spain-, so long as they are reasonable to cover the travel costs and other expenses connected with the maintenance of peace and good administration of those distant provinces."

(Matías de Paz, De dominio Regum Hispaniae super Indos, 1512)

Branding an Indian slave (Mural by José Chávez Morado, 1955-1966, Museo Regional de la Alhóndiga de Granaditas, Guanajuato)

Peter Martyr D'Anghera

, from the Council of the Indies:

"We plan to publish new regulations and to send out new administrators to apply them. The future will show what more we have to do. To say the truth, we hardly know what decision to make. Should the Indians be declared free, and we without any right to exact labour of them, without their work being paid? Competent men are divided on this point and we hesitate.

"It is chiefly the monks of the Dominican order who by their writings drive us to the adverse decision. They maintain that it would be better and would offer better security for both the bodily and spiritual good of the Indians to assign them permanently and by hereditary title to certain masters. [...]

"It may be shown by many examples that we should not consent to give them their liberty. In fact these barbarians have plotted the destruction of the Christians, whenever they could, and have carried out their plans; and although the thing has been often tried, liberty only conduces to their destruction. They only wander about, idle and ignorant, and return to their ancient rites and abominable ceremonies."

(Peter Martyr D'Anghera

, De Orbe Novo, The Eight Decades, Seventh Decade, chapter IV, 1524)

John Kenneth Turner, The slaves of Yucatan, Fondo de Cultura económica, Mexico city

With his book Barbarous Mexico, John Kenneth Turner introduces the reader to the brutal conditions on the henequen plantations of Yucatan. In 1908, impersonating a potential investor, he gained access to the landowners that lorded it over the Maya peasantry.

"Slavery in Mexico! Yes, I found it. I found it first in Yucatan.

The planters do not call their chattels slaves. They call them "people," or "laborers," especially when speaking to strangers. But when speaking confidentially they have said to me: "Yes, they are slaves." But I did not accept the word slavery from the people of Yucatan, though they were the holders of the slaves themselves. The proof of a fact is to be found, not in the name, but in the conditions thereof. Slavery is the ownership of the body of a man, an ownership, so absolute that the body can be transferred to another, an ownership that gives to the owner a right to take the products of that body, to starve it, to chastise it at will, to kill it with impunity. Such is slavery in the extreme sense. Such is slavery as I found it in Yucatan.

The masters of Yucatan do not call their system slavery; they call it enforced service for debt. "We do not consider that we own our laborers; we consider that they are in debt to us. And we do not consider that we buy and sell them; we consider that we transfer the debt, and the man goes with the debt." This is the way Don Enrique Camara Zavala, president of the "Camara de Agricola de Yucatan," explained the attitude of the henequen kings in the matter. "Slavery is against the law; we do not call it slavery," various planters assured me again and again."

(John Kenneth Turner, Barbarous Mexico, chapter I, The slaves of Yucatan, 1910)

2024 "Friars and Mayas"

|

Bartolomé de las Casas, "Retratos de los españoles ilustres". Engraving by Tomás López Enguídanos and José López Enguídanos (1801)

Bartolome de Las Casas, mural at Santa Maria de los Angeles church, Managua, Nicaragua, Sergio Michilini artist, 1985

San Cristobal de Las Casas, Bartolomé de Las Casas' monument

José Alonso in a Mexican movie by Sergio Olhovich Greene, "Bartolomé de Las Casas", 1993

Indian Freedom: The Cause of Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484-1566. A Reader. Translations and Notes by Francis Patrick Sullivan (Sheed & Ward, Kansas City, Missouri, 1995).