Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

DOMINICANS AND FRANCISCANS IN MAYA LAND, XVIth CENTURY

|

Veracruz, May 2024, celebration of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the first Franciscans in Mexico, the 13th of May 1524. On the placards, the portraits of fray Juan de Palos, fray Andrés de Córdoba, fray Juan Suárez, fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, fray Luis de Fuensalida and fray Antonio de Ciudad Rodrigo

Following is the story of the extraordinary adventure lived by Dominican, Franciscan and other friars among the Maya Indians in Guatemala and Mexico, in the course of the XVIth century.

Guatemala and Mexico had barely been conquered by the Spaniards when friars appeared on these lands. The Guatemala conquest had been led by Pedro de Alvarado in 1523 and 1524. The Dominican friar Domingo de Betanzos arrived in 1529 and Bartolomé de Las Casas in 1535. The conquest of the Chiapas was won by Diego de Mazariego In 1527-1528. In 1537 the Mercedaries settled in San Cristobal. Las Casas and its Dominicans reached it in 1545. The conquest of the Yucatán was harder to win and the three Montejo, father, son and nephew only achieved it in 1543, after a twelve-year struggle. The first Franciscans landed in Campeche in 1544.

The friars left their convents in Europe and sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in order to convert the Indians of the American continent to catholicism, as they had been requested by the Pope and Charles the Fifth.

The Pope and the Emperor believed that the “Seculars” (priests and bishops) would not be able to convert the natives : the lowly priests were often poorly educated and the higher ranks of the church were filled with people from noble families who lived a luxurious life. This state of affairs was to lead later to the Protestant Reform.

On the contrary, the begging orders - the Franciscan order - which was founded by St. Francis of Assisi in 1209, or the Dominican order, established by Dominique de Guzman in 1215, had all the requisites: detachment, high intellectual level, deep-seated faith, closeness to the Spanish kings. They would have the monopole of evangelization during the several next decades.

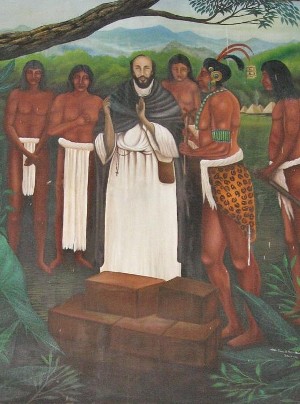

The meeting between the religious and the Guatemalan Mayas, painting by Alfredo Galvez Suarez (1899-1946), National Palace, Guatemala City

In 1521, Pope Leo X, upon the request of Charles the Fifth, gives all necessary powers to two Franciscan friars wishing to go to Mexico. Friar Jerónimo de Mendieta (1525-1604), who wrote the “Religious Indian History”, sums this story, as well as many others, as follows

Two distinguished Franciscans contact the Pope

“The first ones who wished to come here with the benediction of the Pope and the agreement of the Emperor were Friar Joan Clapion, a Flemish man, who had been the very confessor of the Pope, and Friar Francisco de los Angeles, also known as Quiñones, who was the brother of the Count of Luna and who, thanks to his great qualities, his noble ancestry, his education and his adherence of the rule as well as his great charm and capacity to deal with everyone, was one of the senior friars of the order of St. Francis, and as such was soon elected General Minister, and then became Cardinal in residence of Santa Cruz […]. And Pope Leo X gracefully agreed to their request in a motu proprio bull promulgated in Rome on the twenty-fifth of April of the year one thousand five hundred twenty-one, the original of which is kept in the archives of the convent of St. Francis in Mexico […]”.

The Pope grants them all powers in matters of religion

“By the present bull and as a consequence of it, the Pope grants power to these Franciscan friars, in these Indian regions near the ocean and sea, to preach, baptize confess, absolve from excommunication, marry and rule on matrimonial matters, administer sacraments of the Eucharist and the Extreme Unction, without any possible opposition or obstacle from any clerk, laic person, bishop, archbishop, patriarch or other person, regardless of their rank, who would otherwise suffer excommunication and eternal malediction. Such condemnation could only be annulled by the Pope himself, or the superior member of the Order. Where there is no bishop available, the Pope also grants the Franciscan friars ability to consecrate altars and chalices, to build churches and fill them with ministers, and to deliver indulgences that bishops may grant in their bishoprics; and to confirm the faithful, to practice ordination of the first-time appointed monks and minor orders. And many other precisions contained in the bull”.

Portrait of Leo X by Raphael, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, 2021, June

The Pope de facto gives them all power in the Americas

“And in the end, the right to do any other thing, according to time and place, which they would deem useful to spreading the name of the Lord, to convert the infidels, to expand the catholic faith and to condemn all things that are contrary to the teachings of the Fathers”.

(Fray Jerónimo de Mendieta, Historia eclesiástica indiana, circa 1596, around 1596, book 3, chapter 4)

During almost a whole century, friars would administer whole regions, in far away provinces inhabited by the Mayas. The Spaniards were but a few and were concentrated in some towns, in the midst of millions of hostile Indians. The friars would then impose their authority, learn to know the Indians better, build a great number of convents and churches, build new towns… In the midst of many difficulties: precarious living conditions, opposition on the part of the Spanish conquerors who wished to enrich themselves at the expense of the Indians, and resistance from the Indians who were attached to their customs and their gods.

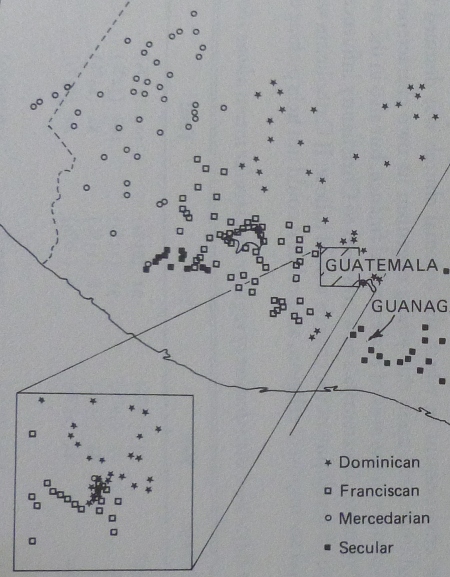

Towns administered by regular and secular clergy in Guatemala, about 1600 (Adriaan C. Van Oss, Catholic colonialism, a parish history of Guatemala, 1524-1821, Cambridge University Press, 1986)

This adventure was narrated by the friars themselves; they have left numerous stories of their life among the Mayas, three of them in particular: Diego de Landa, Antonio de Remesal and Diego López de Cogolludo.

Maya countries: Chiapas on the west, the Yucatán in the north, Petén in the centre, and the mountainous area of Guatemala in the south. The land of war or Verapaz is located on the north side of these mountains.

Antonio de Remesal describes the way of life of the Dominicans in Verapaz, Guatemala

The terrible living conditions of friars in Guatemala

“At the time [1546], friar Tomás Casillas arrived in Chiapas after returning from Guatemala. And according to witnesses, after comforting the friars in the province who were happy to see him and to listen to his wise words and spiritual exhortations, he left for the land of war. On his way he was confronted with the usual problems encountered by traveling monks, hunger, thirst, fatigue, discomfort and lack of shelter, in addition to a solitary trip, difficult terrain while climbing up and down very high mountains, with no marked path other than the one that he chose on moving ground, soaked by water coming down from the summit of the mountain; and the constant rain in this region renders the soil humid on flat ground and makes crossing the rivers so dangerous that at times, they offered their lives to God, several times a day, for His love and that of the inhabitants of these regions, our brothers…”.

Their mission is rewarded

“The head vicar and his companion, friar Alonso de Villalva reached Cobán, the centre of the province where the friars had assembled a great many of its inhabitants, and the friars who were scattered in that general area came there to meet him, each one of them followed by as many Christian Indians as they could gather, as a trophy for their efforts; and the friar vicar was amazed by the great power of the Lord, and the efficiency of His grace, and the power of His divine spirit to give orders to his ministers, when he saw that these barbaric and rebellious peoples had been converted: and he kept saying “Haec mutatio dexterae excelsi”.

A shelter for people in transit run by Franciscans, Salto de Agua, Chiapas

The Dominicans adapted to this precarious life

“He also admired how the religious people present felt comforted by our Lord; those who, having been raised in the most beautiful cities in Spain, in universities and colleges among a crowd of students, in austere convents run by many priests and attended by learned men and nobles of high spirit, were so happy in these forests under a permanent cloudy sky, with torrential rains that stopped only to become even stronger or to be accompanied by thunder that shook the earth, lightning that terrorized the land and electric shocks that burned it with giant flames”.

They live in great poverty

“The food was terrible, corn biscuits harder than stone, without taste, and a little bit of cheese that had to be brought from Guatemala; and most of the time, before reaching them, the cheese stank, had molded and rotted. The beds were made of woven reeds, and all the wardrobe of the friar was used as mattresses, pillows, blankets and bedspreads and was most of the time soaked and full of mud. It was considered a pleasure to take off one’s espadrilles before going to sleep”.

They know how to talk to the Indians

“The head vicar was greatly astonished to see how easily the friars had learned the local language of the region, and he read with great interest the book of grammar written by friar Domingo de Vico who had settled there very recently. It was so well conceived and organized on the model of Latin grammar that no declension, conjugation, tense, class of verbs, tense formation, nouns, verbs and adverbs was missing from it. A very exhaustive vocabulary integrating obscure and rarely used expressions was even included in it and he praised God for all this. He listened with pleasure to anecdotes told by the friars, in which shone God’s mercy for all priests and which saved them from dangers, led them when they were in doubt as to what they should do, and showed them how to talk, saved them from sin and kept them surrounded by grace. It is a pity not to have any written testimony to show the world such extraordinary work as Our Father accomplished with these new apostles”.

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, History of the province of San Vicente de Chiapa and Guatemala, book 7, chapter 14, translated by Chantal Burns)

One of the four statues of evangelists of Mexico (Pedro de Gante, Bartolomé de las Casas < present picture >, Juan Pérez de Marchena, Diego de Deza) which surround the monument of Christopher Columbus, at the Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico City. The authorities removed these statues in October 2021, after activists vowed to pull them down, Columbus being associated with the abuses commited by Spaniards against Amerindians

Principal religious chroniclers of Yucatan, Chiapas and Guatemala

|

Name

|

Order |

Area covered |

Title of work |

|

Diego de Landa (1524-1579)

|

Franciscan |

Yucatan (from the time before Cortes to 1560) |

Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan, 1566 |

|

Jeronimo de Mendieta (1528-1604) |

Franciscan |

A chapter about Yucatan, Chiapas and Guatemala (1529-1596)

|

Historia eclesiastica Indiana, circa 1596 |

|

Antonio de Ciudad Real (1551-1617) |

Franciscan |

Chiapas, Guatemala and Yucatan (1584-1589)

|

Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva Espana, circa 1600 |

|

Antonio de Remesal (1570-1639)

|

Dominican |

Chiapas and Guatemala (from 1528 to 1616) |

Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, 1619 |

|

Bernardo de Lizana (1581-1631)

|

Franciscan |

Yucatan (from the time before Cortes to 1630) |

Historia de Yucatan, 1633 |

|

Thomas Gage (1603-1656) |

Dominican |

Chiapas and Guatemala (1625-1637)

|

The English American or a new survey of the West Indies, 1648 |

|

Diego Lopez de Cogolludo (1610-1686

|

Franciscan |

Yucatan (1540-1656) |

Historia de Yucatan (1688) |

|

Francisco Ximenez (1666-1729) |

Dominican |

Guatemala and Chiapas (from the time before Cortes to 1719)

|

Historia de la provincia de Chiapa y Guatemala de la Orden de Predicadores, circa 1721 |

From : Ernest J. Burrus, Religious Chroniclers and Historians, 1973

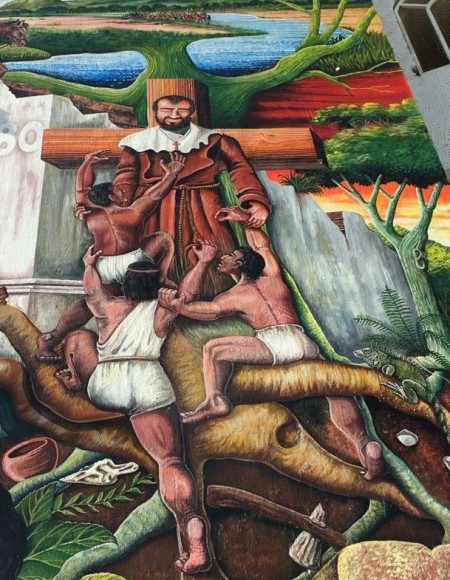

Dominicans in Chiapas (Mural "identidades" by Juan Carlos Barreiro at Villaflores, Chiapas)

Don Antonio de Mendoza, Viceroy of New Spain, to his successor, Don Luis de Velasco:

«The principle responsability which his Majesty has constantly placed upon me has been the Christianity and good treatment of the natives. The means by which I have carried out those injunctions have been the religious orders. In this work they have given me the greatest assistance. Without them little could be done and for this reason I have always tried to favor, honor and love them as the true servants of God and of his Majesty.»

(Relación, apuntamientos y avisos, que por mandado de S. M. dio don Antonio de Mendoza, virrey de Nueva España, a don Luis de Velasco, nombrado para sucederle en este cargo (1550)

Don Luis de Velasco, Viceroy of New Spain:

"The principal thing your majesty should order to be proclaimed is the distribution [of the encomiendas] that has been suggested by the conquerors and settlers, provided only that the grants your majesty should make them would not give any of them jurisdiction, and provided the tributes were very moderate, of which the encomenderos would give a sixth or a seventh for the support of the churches and monasteries.

The friars and priests would be in charge of the administration of the sacraments and the religious instruction of the natives, giving the principal responsibility for this to the prelates and taking it away from the encomenderos. In this way you will discharge your royal conscience, do right by those who have served you, and keep the Spaniards in the country and make it secure.

Those who inform your majesty that the land can be held by friars alone, without being defended by Spaniards who have the means with which to serve and something to lose if they don’t do their duty, in my view deceive themselves and do not know the natives well, because they are not so firm in our holy faith, not have they so forgotten the evil beliefs they had in the time of their infidelity, that such great matters should be trusted to their virtue."

(Don Luis de Velasco, viceroy of New Spain, to the emperor, 1553)

The Mercedarians came to Chiapas and Guatemala before Franciscans and Dominicans. Today, May 2023, the Center Padre Varela, in Guatemale City, assists persons released from jail.

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

Carlos María Esquivel, 1862. In the Monastery of Yuste, Saint Francis Borja visits Charles the Fifth. Canvas in Sevilla cathedral, Spain.

The emperor Charles the Fifth (1500-1558), close to the begging orders, requests them to evangelize the Americas. He himself retired in a convent at the end of his life.

During a visit to Yuste by Francisco de Borja, Charles V asked him:

‘Do you remember what I told you at Monzón in 1542, that I would retire and do exactly what I have done?’

‘I remember very well, Sire’, Father Francisco replied.

‘Well you can be sure’, said the emperor, that I have told no one else except you and so-and-so’, naming a prominent gentleman [Luis de Avila y Zuñiga?].

‘Now that I have followed through, you can talk about it’.

Fray José de Sigüenza, Historia de la Orden de San Jerónimo, 1605

The Franciscan emblem, which was often times carved on the façade of Franciscan convents (Campeche, Baluarte de San Carlos).

"Two arms crossed; one, naked, of the crucified Christ, the other in its wide monastic sleeve, St. Francis’s. The palm of either hand is marked with the print of nails. It is an emblem one sees on many churches in Antigua, and indeed all over Guatemala. Here, in Central America, it seems to be the regular coat-of-arms of the Franciscan order. In Europe, the Minorites were much more chary in their use of this striking emblem. Indeed, I remember to have seen it only once outside Central America: in the archaeological museum of Aix-en-Provence. Perhaps it was only in the New World, where their power and wealth were so prodigious, that the Franciscans ventured to state the claims of their founder so openly and in such unequivocal terms."

Aldous Huxley, Beyond the Mexique Bay, 1934

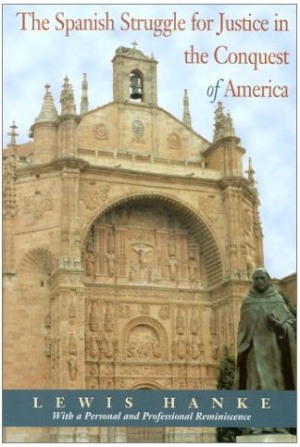

The convent of San Esteban, in Salamanca, Spain, starting point for Dominican missionaries (cover of the book by Lewis Hanke, The Spanish struggle for justice in the conquest of America, 1948)

Saint Francis of Assisi, Museo del Mundo Maya, Merida, Yucatan

Fray Pedro Lorenzo de la Nada founds the village of Palenque, Chiapas, 1567

“Fray Pedro [de la Nada] walked towards the north of the Lacandón Jungle, where he discovered many Chol families still living in small hamlets according to their ancient customs. These families he gentle invited to leave their huts in order to follow him to a new town which he had prepared for them near the river Chacamáx, at the foot of a range of hills where some ruins of singular beauty were situated. With the Indians who accepted his invitation, Fray Pedro founded, by the year 1567, the town of Palenque, giving homage with this name to the ancient “palenque” [“fenced site, fortified place, walled city”] whose vestiges he had encountered at a short distance from the new site.”

(Jan de Vos: Fray Pedro Lorenzo de la Nada, Misionero de Chiapas y Tabasco, 1980, 34)