Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Learning the Maya languages

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

LEARNING

THE MAYA LANGUAGES

|

The most notable pioneering efforts in the study of the Maya languages can be identified with the evangelization efforts, the "Spiritual Conquest", of the region entrusted to the regular orders of the Dominicans and Franciscans. The acquisition of indigenous languages was not uninspired by a quest for knowledge, but rather as a means of spreading the gospel. The preoccupation of the missionaries was to prepare dictionaries and fundamental grammars. They also translate liturgical texts, prayers and songs, and an outline catechism. Their grammars, usually termed artes, have proved to be valuable to later scholars interested in Mayan languages, and some of their vocabularios have never been excelled.

Alta Verapaz, 2023, a bilingual Spanish and Mayan Kechki Language lesson (Association Enfants du Monde)

Many Franciscans knew the Maya language

"They did not miss an opportunity (as they say) to badmouth us during this conspiracy, going as far as pretending that the priests did not know the indigenous language, which is like saying that the mid-day sun does not shine, without any comments from anybody. Father Villalpando mastered the dialect so quickly that it seemed a miracle, and he established the grammar of the dialect, and this impressed the Indians. Father Landa, future bishop, improved it so much that, as we came from Spain, we got trained thanks to this precise and correct manual, and we are used to saying that those who do not follow it to the letter speak a coarse language. Friar Antonio de Ciudad Real, after working during forty-six years, composed the vocabulary called Calepino because of its dimension and because it covers everything, a work that represents, in its final version, more than a thousand two hundred pages. Father Solana wrote sermons for Sundays and holidays and composed a small vocabulary. Father Torralva wrote another book of sermons for Sundays and holidays. Father Coronel, who recently died, had a book of spiritual discourses and mysteries of the faith printed in Mexico, a small work that contains all the Christian doctrine, a manual of confessions for the new priests, and a simplified grammar to learn the language. All the religious men, priests and monks alike, have used these writings in order to become perfectly bilingual; nevertheless their authors came from Spain. We do know that those who entered into religion and were native of Spain have been and are great interpreters, and my good will is not enough to praise them, but the great masters of the Maya language came from Spain. I do not understand how some (who did not know the Maya language) affirmed that most of the religious men ignored the language (I did not forget a royal decree of which I spoke, and I assume that it was not published without proper motivation, as well as another one published for the clergy)."

(Diego Lopez de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book 8, Chapter 7)

(it is easy to understand Cogolludo’s indignation: in 1574 for instance, Juan López de Velasco, cosmographer-columnist of the Council of the Indies, wrote in the chapter devoted to Yucatan in his book on "Geography and universal description of the Indies" : "According to the Bishop, in the ten monasteries in existence in 1570, there were at most twelve priests friars, and four of them knew the language (Maya) and could hear confession from more than thirty or forty thousand Indians.")

« It is known that many manners of Doctrines have been composed already in this land in the languages of the naturales, … thus minor or brief Doctrines, with which children are taught and other more elder, in what more extensively adults and the more gifted can understand of our faith. Of the minor ones called Christian Doctrine, of which we here request a copy, four or five versions are in print, which contain the same substance and meaning, ever though they differ somewhat in the manner of proceeding and in different word choice.”

(Códice Franciscano, siglo XVI, 29)

Present distribution of Maya languages in Mexico and Guatemala (from: Gran Museo del Mundo Maya, Merida)

Fray Antonio de Ciudad Real:

Antonio de Ciudad Real was the most accomplished Maya linguist of this time, and his famous Gran Diccionario ó Calepino de la lengua Maya de Yucatán (so named from Calepinus’ famous polyglot dictionary published in 1502), is the work known to us today as the Diccionario del convento de Motul. He is said to have taken forty years to write this book.

The Mayan-Spanish dictionary of Antonio de Ciudad Real had already been compiled by 1604. Born in Spain, Ciudad Real entered the Franciscan monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo in 1566 at the age of 15. He arrived in Yucatán in 1573, in the company of Fray Diego de Landa. He was appointed as secretary of Alonso Ponce, Visitor of the Franciscan Provinces, for his inspection tour of the missions throughout New Spain, during five years (1584-1589). He became Provincial of the Franciscan Order in Yucatán. He died in 1617.

The manuscript of the Diccionario de Motul, in three large quarto volumes, in all counting over 2,500 pages, is not only a dictionary but a grammar and an encyclopaedia as well, for most of the 19,000 word citations are accompanied by copious examples of phrases and sentences.

The Motul dictionary created by Antonio de Ciudad Real

"The Reverend father Antonio de Ciudad Real, born in the town of the same name, son of the convent of S. Juan de los Reyes of Toledos, arrived in Yucatan with the mission group led by Bishop Diego de Landa who came back after being ordained. He was a chorister, and an authority on Latin and a philosopher, and he learnt the language of the Indians with such perfection, that he became the greatest master of the language in the whole region. Thanks to his gift, he was able to preach, teach and write sermons for the saints’ days and for every day of the year, with the greatest elegance requested in that language. Not only did he create the vocabulary, one of which begins with the castellan language, but he also created a remarkable piece of work that was called Calepino, from the Yucateca or Maya language, because of its exhaustive character. Calepino is derived from the Yucateca or Maya language. This work contains six volumes of writings, with two hundred pages each, and it helps in solving all difficulties encountered in learning the language, and in it are found all about the various locutions, which are many, with none missing as the work is so complete. This occupation kept him busy for 40 years, and if the language had not been proper to the region but applied to other regions as well, it would no doubt be one of the most famous works published in these kingdoms."

Calepino Maya de Motul, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1984

His trips through Mexico and Guatemala

"It was not his sole occupation, since the provincial people often took him along and used him as secretary, knowing that he was very competent and interested in Government matters. He accompanied the most reverend father Alonso Ponce from the saint province of Castile, fifteenth general commissary of New Spain, in all his trips, arduous tasks and exiles, as told by Father Torquemada in his Monarquia Indiana (and that I omit since it is not linked to my narration). When he was his General Secretary, he wrote a curious treaty on the greatness of New Spain and the events that took place, with an in-depth knowledge of the subject. He went with the most reverend Father general commissary to Castile, and the general commissary having died, he decided to return to Yucatan to use his perfect knowledge of the language for the good of the Indians. He travelled with the priests of the mission that Father Pablo Maldonado led in the year 1592. The Franciscans of the province rejoiced when they saw the return of a man so indispensible, and later on he was elected Provincial of Yucatan, as I already said."

The trip of Antonio de Ciudad Real in Yucatán may be found in the section on :

"The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century"

His great human qualities

"He loved the Indians with great affection, as he had a merciful character and extraordinary indulgence. He acted with much maturity and prudence, getting advice before starting any undertaking . As he showed some resistance to the haste shown by the Governor of the region, D. Carlos de Luna y Arellano, in dealing with his affairs, there arose between both of them some conflicts that were later reported. During the whole time of his peregrinations, and during his stay in Spain, he never stopped his work on what I called Calepino, and this is confirmed by Father Lizana who heard it said many times. After providing priests and lay people alike an example of a most commendable life as a prelate and as a subordinate who was well-known as a fervent priest, he left his earthly life in the convent of Merida on 5 July 1617, at 66 years of age, of which 51 years were devoted to the church."

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatán, book 9, chapter 16, translated by Chantal Burns)

A translator of Mayan languages

A, preposiçion: ti. Vt: a,

preposiçion por çerca: tacan; nedzan.

Aa .l. ee: assi que esso pasa. es como admiracion.

Aha: no lo dezia yo .l. no os auia yo de coger.

Abadesa: ix

kin; v cħun v than.

Abahar: ouox.t. ouoxte u kab ca kinlac: abajate las manos, &.

Abalançarse: pic cħin ba; pul ba; çithpom.

Abarcar entre los braços: mek; hol mek.t.

Abarcar entre las manos y la tal abarcada: lot.

Abarca, y qualquier calçado de cuero: keulel xanab,

Abarrajar barro en la pared arrojandolo: pak cħin.t.; pak pul.t.

Abarrer o arrebañar: volmol: haymol. Ala de aue: xik.

Alabar y alabança: ticħ anumal; nachcunah pectzil; nohcinah; titzcunah. lo contrario de esto vease desacreditar.

Alabar alguna persona diçiendo bien de ella: vtzcinah pectzil.

Alabarse: vide: jatarse.

Alabastro: çac yeel bach; çac yeel becħ.

Alacran: çinaan.

Alagar: vide infra: al hagar.

Al amor del agua: tu pul haa; tu hah haa; tu kak haa.

A la otra parte: citan tu pach.

A la postre: tu pach.

Alarde: v kukum tok; v kukum katun.

Alargarse algo: chauachal.

Alargar anssi: chauaccunah.

An extract of the maya dictionary of Motul (1590?). At the time, dictionaries were presented in the Spanish-Maya form, since monks used the alphabetical list of the Spanish-Latin dictionary by Antonio de Nebrixa (1492) as a basis for work.

Merida, Yucatan, national anthem contest in Mayan language, 2024, June

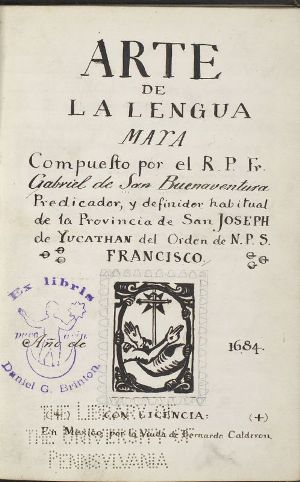

Gabriel de San Buenaventura

Born in Seville, Spain, he was a friar of the Franciscan order, and spent many years in Yucatán, where he was still living in 1695. He wrote "Arte de la lengua Maya", printed in Mexico, in 1684. Only a few copies of this work are known. It has been reprinted, though not with a desirable fidelity, by the Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg, in the second volume of the reports of the Mission Scientifique au Mexique et à l’Amérique Centrale, Paris, 1870. San Buenaventura was also the author of a "Vocabulario Maya y Espanol," containing descriptions of the medical and botanical products of the country, which, at the beginning of the 19th century, was in the Franciscan convent of Valladolid, Yucatan, but is now lost.

PRIMERA CONJUGACION

Indicativo.

Presente

[Singular]

nacal in cah yo subo

nacal a cah tu subes

nacal v cah aquel sube

Plural

nacal ca cah nosotros subimos

nacal a cahex vosotros subis

nacal v cahob aquellos suben

Preterito Imperfecto

[Singular]

nacal in cah cuchi yo subia

nacal a cah cuchi tu subias

nacal v cah cuchi aquel subia

Plural

nacal ca cah cuchi nosotros subiamos

nacal a cahex cuchi vosotros subiades

nacal v cahob cuchi aquellos subian

An excerpt of "Arte de la lengua Maya" by fray Gabriel de San Buenaventura (1684)

Vocabulario comparativo de los idiomas mayas de Guatemala, Nora C. England, OKMA 2003

The first Maya grammar by Luis de Villalpando and Diego de Landa (in the 1540s)

"As soon as this Landa saintly man arrived in our region, he showed signs of what he was to become, as Friar Luis de Villalpando said. Villalpando taught him the Maya language and the grammar that he had created. He became, as well as his other companions, such an expert in the Yucatan language that within a few days, he spoke and preached in that language as if it were his mother tongue. His master, Friar Luis, had drafted the grammar without any outside help and some important rules had been omitted from it : the happy Friar Diego Landa added them and improved other rules. I believe that none have been added since then, none have been suppressed, whether wrong of defective ; and they are nevertheless numerous and very difficult to understand. In a short time, these multiple rules have been simplified and summed up in such a way as to explain all sentences and phrases and to make them very easy to learn. It is a mystery that the religious men coming from Spain are able to learn perfectly the grammar within two months and preach to the indigenous people a few days later; and they are sometimes better at it than the indigenous people born here. There is no doubt that those who learn the language with the help of grammar are better able to master it than those who learnt is naturally, by being born here and by speaking it since childhood. It is a language so rich that it is never quite mastered, and so logical in its peculiarities that all the words, verbs and nouns alike, find their origin in local phenomenon that apply only to them. Some say that the Yucateca language is barbaric but it is because they themselves are barbarians and they judge colours like blind men."

(Friar Bernardo de Lizana, Historía de Yucatán y Devocionario de Nuestra Señora de Izamal, 1633, Part II, Chapter VI)

The Municipal Academy of Maya language of Merida holds Maya Yucatec language classes. At present the Maya language is in danger of disappearing because of globalization and social mobility. The people who speak Maya are in the range of 40-50 years old. Young people less than 25 years of age do not use it as a primary language.

Some brief and short Rules for the better learning of the Indian tongue, called Poconchi or Pocoman, commonly used about Guatemala, and some other parts of Honduras (1655).

"Although it be true that by the daily conversation which in most places the Indians have with the Spaniards, they for the most part understand the Spanish tongue in common and ordinary words, so that, a Spaniard may travel amongst them, and be understood in what he calleth for by some or other of the Officers, who are appointed to attend upon all such as travel and passe through their Towns.

"Yet because the perfect knowledge of the Spanish tongue is not so common to all Indians, both men and women, nor so generally spoken by them as their own, therefore the Priests and Fryers have taken pains to learn the Native tongues of several places and Countreys, and have studyed to bring them to a form and method of Rules, that so the use of them may be continued to such as shall succeed after them.

"Neither is there any one language general to all places, but so many several and different one from another, that from Chiapa and Zoques, to Guatemala, and San Salvador, and all about Honduras, there are at least eighteen several Languages; and in this district some Fryers who have perfectly learned six or seven of them.

"Neither in any place are the Indians taught or preached unto but in their Native and Mother-tongue, which because the Priest onely can speak, therefore are they so much loved and respected by the Natives.

"And although for the time I lived there, I learned and could speak in two several tongues, the one called Chacciquel, the other Poconchi or Pocoman, which have some connexion one with another; yet the Poconchi being the easiest, and most elegant, and that wherein I did constantly preach and teach, I thought fit to set down some Rules of it, (with the Lords Prayer; and brief declaration of every word in it) to witnesse and testifie to posterity the truth of my being in those parts, and the manner how those barbarous tongues have, are, and may be learned.

(A new survey of the West-Indias: or, the English American his travail by sea and land: containing a journal of three thousand and three hundred miles within the main land of America. By the true and painful endevours of THOMAS GAGE, preacher of the word of God at deal in the county of KENT. Second Edition, enlarged by the Author, and beautified with MAPS. LONDON, Printed by E. Cotes, and sold by JOHN SWEETING, at The Angel in Popes-head-alley, M. DC. LV.).

Merida, Yucatan, 2023, January, Mayan languages digital activism summit, to promote Mayan languages in digital spaces

Friar Gerónimo de Mendieta:

"The blessed doctors, Saints Jerome and Isidore, wrote special tracts in which they informed the faithful of the ecclesiastic authors of the early church. Following in their footsteps I felt that I should devote a special chapter to this theme, which would demonstrate how much we owe to the pioneers of the Church of New Spain, God’s vineyard, who not content with clearing the ground, tilled and watered it with the sweat of brethren, and made it possible and easier for those who followed. They achieved this by employing the native language (language being the most essential element in the preaching of the Holy Gospel) and by their instruction in the Christian life. We owe those who compose and translate tracts into Náhuatl and other native languages an enormous debt, for like the blessed Apostles, they were inspired by the Holy Spirit. Their mastery of these languages is an example of devout application and human diligence; they became linguistic experts."

(Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta, Historia Eclesiástica Indiana, Libro IV, Capítulo 44, De lo mucho que escribieron los religiosos antiguos franciscanos en las lenguas de los indios)

San Felipe Ecatepec, Chiapas, 2023, December, incorporation of Tseltal and Tsoltsil interpreters in the hospital to facilitate communication with the indigenous

An adventurous translation:

"As to the last words of Jesus of Nazareth, when expiring on the cross, as reported by the Evangelists, Eli, Eli, according to St. Matthew, and Eloi, Eloi, according to St. Mark, lama sabachthani, they are pure Maya vocables; but have a very different meaning to that attributed to them, and more in accordance with His character.

"Well, this is exactly the meaning of the Maya words, HELO, HELO, LAMAH ZABAC TA NI, literally: HELO, HELO, now, now; LAMAH, sinking; ZABAC, black ink; TA, over; NI, nose; in our language: Now, now I am sinking; darkness covers my face! No weakness, no despair. He merely tells his friends all is over. It is finished! and expires."

(Vestiges of the Mayas, or Facts tending to prove that Communications and Intimate Relations must have existed, in very remote times, between the inhabitants of Mayab and those of Asia and Africa, by Augustus Le Plongeon, New York, 1881)

Photograph of Augustus Le Plongeon's discovery of the Chacmool sculpture in the Platform of Eagles and Jaguars at Chichén Itzá (1875)

|

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

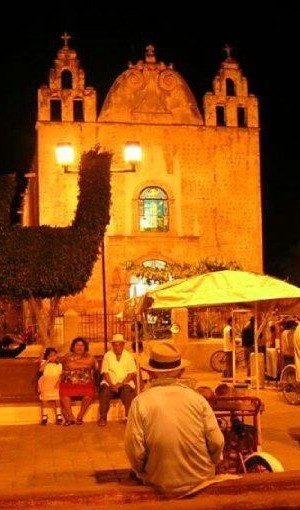

The convent of Motul, where they found a manuscript of the diccionario de Motul, preserved today in the Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island (Motul, patronal feast, 2022, May 16)

Convent of Ticul, night, 2022

This convent was founded in 1591, its first construction made in 1624, then another completed in the year 1640. A partial reconstruction took place in 1897. It has suffered subsequent modifications during the last century : especially the change in the floors led to loss beautiful tombstones. Into the convent they discovered a Mayan dictionary, writen around 1690.

.

Mérida, Yucatán, 2024, June, Maya language song and composition concourse uk'aavil in kaajal (the song of the people)

Fray Gabriel de San Buenaventura "Arte de la lengua Maya" (Mexico, 1684),