Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Grouping together the Indians

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

GROUPING TOGETHER THE INDIANS

|

The missionaries and Spanish officials pressed for relocating the Mayan populations from their dispersed settlements into clustered villages. The process, called reducción ('reduction') or congregación ('bringing together'), made it easier to perform rituals, indoctrinate the Indians, and collect tribute from them.

The beginning of the effective organization of the reductions dates to 1531, according to the instructions communicated to the second Audiencia of New Spain. In each reducción de indios there was required to be a church staffed by a priest.

Another Spanish edict of 1578 describes the purpose as follows: “In order that, as the rational beings they are, they may be able to be truly Christian and political, it is essential that they be gathered and brought into settlements and not live scattered lives on the mountains and in forests.”

Mayas leaving their ancient habitations, Museo de la Cultura Maya, Chetumal, Quintana Roo

Antonio de Remesal depicts the urbanistic work of the Dominicans into Chiapas and Guatemala:

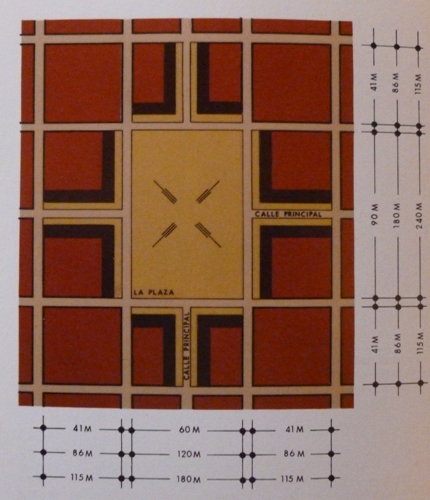

The Dominicans design towns in the shape of a square

[…] "The Fathers began by trying to regroup the Indians, and to organize their society as a social republic, so that they would go to church and sermons more easily, as well as anything else related to their government. They therefore designed a map to build everything in a uniform way. The church, whether big or small depending on the number of inhabitants, got the best spot. Next to it they decided to build the house of the Father, and in front of the church a very big plaza, distinct from the cemetery, across from the town hall building that would be next to the jail and nearby the inn or common house where foreigners would stay. The rest of the village was designed in a most square manner, with straight and wide streets running North-South and East-West, and shaping the village as a square map (cuadras)."

Hunucmá, Yucatán, in the main square the Virgen feast (2024, January)

The Indians refuse to move

"This being done, the essential part was still missing, i.e. would the Indians want to move, since these people love their huts, cling to their habits, love their mother mountain, the ravine of their childhood; and even if the area to which the Indian is used is unsanitary, dry and sterile, it is extremely difficult to remove him from that place. The Fathers began very progressively and with much prudence to talk to them about moving away from their dwellings, and precisely about regrouping people and houses; and since it was impossible to do so with the use of strength and stick, the Fathers had to make sure that their proposal was agreeable to the Indians. Some villagers said yes, understanding thanks to the Fathers arguments that it would suit them. Others, who could not make up their mind whether they liked this idea or not, were convinced because of their love for the Fathers and because they were sure that the Fathers had only their well-being in mind. Others, just like courtesans, said a timid yes but never had in mind that they would move; on the contrary they were all strongly determined not to leave their old house full of smoke, which they loved more than the most magnificent and golden palaces of all of Africa or Europe. And for the same reason, others frankly said that they did not wish to move and abandon the houses in which they were born."

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 8, chapter 24)

The friars have their own method to move the Indians

"The method used by the Fathers to move the villages was as follows : First, they and the caciques and the personalities examined and measured the new spot ; and if the representatives of one of the old villages found it suitable to the regrouping of all the other villages, they so decided. First, they began to cultivate the nearby fields and while corn was growing and became ripe, they built the houses and let them dry; and when the corn was ready to be picked from the fields (milpas), they all moved to the new place on that very day with celebrations and balls that lasted several days so that they forgot about their old dwellings. And the priests became such masters at building new villages and moving the Indians there that his Majesty requested, by royal decree sent to Valladolid on 21st November 1558, secretary Francisco de Ledesma, renewed in Elvas on 15 December 1580, secretary Antonio de Erazo, and in Madrid on November 8, with the same secretary, the President and the Auditors of the Audience of Guatemala, that they gather all the prelates and main priests to examine together the move of some villages, and after receiving their opinion and advice thereon, they communicate them to him."[…]

Grouping together the indians, by Federico Fernández Christlieb and Pedro Sergio Urquijo Torres

The work has to be redone again and again

"But who will say how much the Fathers of our saintly Order worked and suffered to establish these villages, build the houses, create churches and all that was required for the founding of a republic ? They were the ones pulling the strings, measuring the streets, deciding where the houses would stand, supplying the materials, and even though they were not professional architects, they became great masters at construction. They cut the reeds, shaped the raw bricks with their hands, shaped the beams, laid down the bricks, started the lime ovens, and were sure to adjust to learning how to perform every possible new job, including the lowest ones. They suffered from so much fatigue, perspiration, worries and upsets to create these establishments and oftentimes, after having set them up and once the Father was gone, the inhabitants returned to the woods, and they had to be gathered again, called again, pampered and installed in their new houses while the old ones were demolished and the places of their old beliefs were destroyed; all the while they had to study the manner in which to talk to them and to treat them with love and affection, peace and charity, to make them understand that all of this was done for their own good, without any other consideration."

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vincente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 8, chapter 25)

Tecpatán, Chiapas: the Dominican monastery

The convent is an enormous mass dominating the townscape today, as a physical symbol of the new order, both religious and civil, which the friars had imposed on the Indians.

The establishment of Rabinal, Baja Verapaz, Guatemala (1538)

“Father friar Bartolomé de Las Casas and Father friar Pedro de Angulo, who had been living since the beginning of the year in the villages of the Cacique Don Juan, talked to him about the most efficient way to evangelize the whole province. And they did not find a better idea than to regroup the Indians in new places, and took them away from the mountains and the caves where they lived, scattered in poor hamlets that did not have more than six houses, separated by a distance of at least the range of a musket. They wondered which villages to tackle first and discovered that those of Tococistlán and Rabinal were the best ones. Don Juan started to negotiate with sound arguments; but the Indians brought forward better arguments and got ready to point their arms toward him, horrified as they were by the idea of leaving the valley where they were born. The Fathers came back to pursue their discussion with the Indians, who got so angry that the Fathers were ready to stop loving them. But the saintly preachers avoided antagonizing them further and, thanks to their patience that helped vanquish the greatest difficulties with the help of our Lord, they slowly managed to regroup almost one hundred houses under the same name of Rabinal, not where the present village stands, but a mile further down. They built the churches and the Indians enjoyed the communal life, were happy to hear mass every day, to listen to the sermons of the Fathers, to participate in the discussions and to learn new techniques that seemed wonderful to them since they had limitations in that field. They invited each other and the Indians of Cobán discreetly came down to observe this new way of life that their neighbours from Rabinal enjoyed.”

(Friar Juan Bautista Méndez, Crónica de la provincia de Santiago de México de la Orden de Predicadores (1521-1564), Book 2, chapter 4)

Rabinal. On the church, the black and white Dominican emblem

The churches are more or less well built

"Once the Indians had settled in their new towns, churches were built as well as the houses of the priests, and after seven or eight years, many of them were completed and covered, and were as beautiful as those in the villages of Spain. Afterwards, our Lord provided the province with a lay priest named Friar Melchor de los Reyes, a great stone carver, such an expert in his field of work that at least six Indians were required to bring him all the materials he needed. He died in the year 1577 and we missed him much, since afterwards a few visiting Fathers tried to build, thinking they were capable, without any help from craftsmen and masters of this specialty; they spent a lot of money and the churches have today crumbled, such as that of Saint Luc near the town of Santiago; and others are about to crumble because they were built higher than what the foundations can bear, and the frame has been designed according to metaphysical considerations, such as the church of the Zacatepeques, which looks scary once we are inside. The church of Chimaltenango looks very original and curious, nothing like it can be found anywhere else in all the Indies, as the water from one side of its roof runs towards the Ocean sea, or North sea, and the water from the other side of the roof runs towards the South sea."

The fountain of Chimaltenango. Built on the continental divide, this fountain has half of his waters flowing to the Atlantic Ocean and half to the Pacific Ocean

The decorations become richer and richer

"The decoration of the churches was poor at first and the altarpieces and sculptures were rather plain, because of the lack of craftsmen; time went by and thanks to the Fathers’ actions, the Indians began to show an interest in these things and were very generous to offer them to God, and they should be thanked all the more since the land of Guatemala is less rich than others in the Indies. There is not one church that does not possess at least ten or twelve statues or more, each with its banner that the Indians, helpers and friends of the donor carry during processions. Each one of them kept these statues at home on a well decorated altar, with things belonging to those who offer them. This procedure was found to be wanting, and the Fathers had the statues brought back to church, and in Xocotenango, Father friar Victor de Carvajas was upset about this as he understood faster than anybody else what was going on, zealous as he was. The ornaments already given and being given every day are abundant since some Indians and some villages competed in these gifts as they were encouraged by the inhabitants. To give a complete idea of the vastness of these gifts, when I left for New Spain, I started an inventory of the silver and ornaments belonging to the villages I crossed, and their number and quantity reached such a level that a very thick book would have been necessary to register them: in Zumpango only, ministered by the Father friar Juan de Ayllón, an Indian had given silver and ornaments of a value of 5,580 tostones ; and I will dare affirm that in the sole region of Zacapula, the Indians have been more generous than all those ministered by the other Orders in the whole province of Guatemala, Chiapas and Zoques. And yet there is no possible measure or comparison, as the other regions have many advantages since their inhabitants are wealthier."

The church of Sumpango, painted onto a giant kite, during the "Giant Kite Festival" of the town

The friars are able to pacify the region

"Commendable is the way in which the Indians, once installed in the villages, took up music, songs as well as instruments, particularly in Chiapa and among the Zoques, because they communicated more with the masters of New Spain; among them, those from Cinacantlán stood out, and also those from the very village of Chiapa. This played a big part in totally appeasing and pacifying the region, as when the priests entered the province of Chiapa, there were many Indians at war who had rebelled against the bad treatments from the Spaniards and who saw that the Fathers favored and defended the indigenous people and set up republics where they could live in peace, and therefore the Indians took shelter there voluntarily. Following the information that the Fathers had transmitted to the Counsel, his Majesty issued a royal decree promulgated in Valladolid on 9 October 1549, secretary Juan de Sámano, told the Audience that no Spaniard should go and conquer the Indians, only the priests could go toward them with the word of predication, because they were expected to pacify them in this manner, as was done in Verapaz."

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 8, chapter 25, translation : Chantal Burns)

The church of Saint Lawrence in Zinacantán. The Tzotzil village of Zinacantán is located 11 kms from San Cristóbal de Las Casas. There was one of the first dominican convent in Chiapas (2023, June)

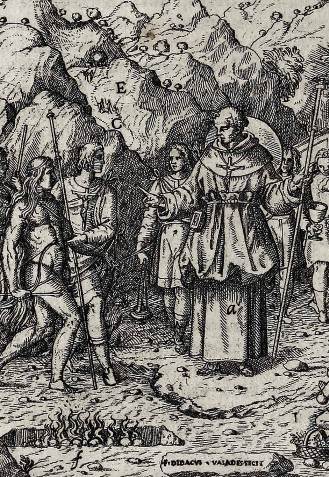

Diego Valadés, Indian republics

"I promise to provide examples of the successes of the Indies, among whose inhabitants we not only lived, but we were also in charge of them; we believe that this not only served their enjoyment but that it was also beneficial, for ultimately they clearly appreciated the principles, the development, and the practical application of rhetoric, as Cicero attested when he said “There existed a time when men, in the manner of beats, roamed the earth and struggle for life, and they had neither justice nor virtue of reason but only force. None were legitimate nor knew with certainty who were his children. Then, an excellent man, impelled by some higher motive to unite the men dispersed across the plains and hiding in the woods, converted the fiery savages into peaceful and gentle men”. I say that the admirable effects of this influence are nowhere more clearly apparent than in the pacification of the Indians of the New World of the ocean sea."

Fray Diego Valadés, Rhetorica Christiana, preface, 1579

Francisco Solano, Historia urbana de Iberoamérica - La ciudad iberoamericana hasta 1573, Comición nacional del quinto centenario, Madrid, 1987: the "cuadras" established by the Ordenanzas de descubrimiento by Felipe II

Samples of congregation:

"To Chaul [Chajul] in the sierra of Zacapulas were brought the settlements of Huyl, Boob, Ylom, Honcab, Chaxá, Aguazap, Huiz, and four others, all of which were associated with smaller, dependent settlements; this was undertaken at the request of the [Dominican] fathers who founded the monastery [of Sacapulas] and by the order of Licenciado Pedro Ramírez de Quiñones […] To Aguacatlán [Aguacatán] and Nebá [Nebaj] were brought together the settlements of Vacá, Chel, Zalchil, Cuchil, and many others upward of twelve in number. To Cozal [San Juan Cotzal] were brought together Namá, Chicui, Temal, Caquilax, and many others […] The town of Cunén was also formed by congregating many smaller settlements."

(Fray Antonio de Remesal, Historia general de las Indias occidentales, libro octavo, capítulo XXV, Algunos pueblos mayores a que se juntaron otros)

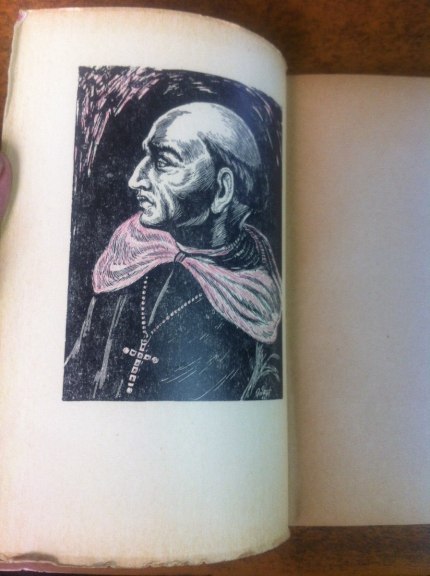

Las Casas' portrait (in Agustín Yáñez, Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, el conquistador conquistado, SEP, Secretaria de Asuntos Culturales, Cuadernos de la lectura popular, México, 1966)

Bartolomé de Las Casas’ point of view on religious constructions

"The prelates of the cathedral and parish churches, and those of the Orders have the obligation to put just and God-fearing persons in charge of giving an estimate of the buildings, churches and convents, as well as of the funds used for their construction and the amounts charged per day and for the materials provided by the Indians, so that they are reimbursed. The proof of this conclusion is that the land and the buildings erected on it belong to the Indians and that we seized them by no other means than violence, as I have already mentioned. These thieves have therefore the obligation to restitute them, and I include as thieves those who manage the churches. But since they are dedicated to God, they cannot be used for lay purposes nor can they changed their objective; their value must therefore belong to the Indians, as well as the value of the land on which they were built as well as the cost of the work. Such is the opinion of Saint Augustine and Saint Gregory, who tells the story of Jews who had complained to him that their synagogues had been confiscated from them, on the order of a bishop, to turn them into churches. He requested right away an estimate of their cost and that payment be made to the Indians, not believing that their demolition was necessary for justice to be rendered.

"I said that this was the business of the prelates and other superiors, since it is their essential duty to obtain restitution of a wrongly obtained asset.

"I will add that they use things that do not belong to them, against the will of their real owners, which is a real robbery ; that they deny justice to those who have been wronged ; that they give a bad example to the leaders who think that they are de facto allowed to keep what they stole by seeing prelates and priests quietly enjoy churches and monasteries built on stolen land, which the Indians have paid with their blood ; and that they conclude they have no more obligation than the others to give back what they took ; on the contrary, if they saw the clergy men give back to the Indians the land that was taken from them to build churches and convents, they would probably follow their example ; at least we can assume that they would not live with such great indifference and that their salvation would not be so seriously exposed."

(Reply of Don Bartolomé de Las Casas to the questions posed to him on Peru’s affairs in 1564, Tenth conclusion on the fifth doubt, Translation : Chantal Burns)

Morelia, Monument "The Builders" (the sculpture depicts a Spanish friar ordening a half-naked indigenous to cut a block of stone; indigenous activists demolished the monument, considering the work racist, in February 2022)

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

San Cristobal Verapaz, Guatemala: a rectilinear street leading to the lake

In 1573 the King of Spain, Philip II, decreed an extensive set of rules for the building of towns and cities in the Americas. These ordinances confirmed that all new towns must have a central plaza surrounded by important buildings with portales or arcades, and from which the principal streets, laid out in a grid pattern, shall begin.

"Phillip II: Ordinances for the discovery, the population and the pacification of the Indies , dated in the Woods of Segovia, the thirteenth of July, in the year fifteen hundred and seventy-three

"110. Having made the discovery, selected the province, county, and area that is to be settled, and the site in the location where the new town is to be built, and having taken possession of it, those placed in charge of its execution are to do it in the following manner. On arriving at the place where the new settlement is to be founded - which according to our will and disposition shall be one that is vacant and that can be occupied without doing harm to the Indians and natives or with their free consent - a plan for the site is to be made, dividing it into squares, streets, and building lots, using cord and ruler, beginning with the main square from which streets are to run to the gates and principal roads and leaving sufficient open space so that even if the town grows, it can always spread in the same manner..."

A map of the town of Antigua (Guatemala), in front of the convent of La Merced

"The Dominicans not only gave the Mercedarians jurisdiction over Indians in the city [of Guatemala]; they were also given jurisdiction over Indians outside [the capital] in the towns of Quiché and Zacapula [Sacapulas]. All that is nowadays [1615] administered by the [Mercedarian] monastery of Xacaltenango [Jacaltenango] witch was formerly under control of the Dominicans. Friar Pedro de Angulo and Friar Juan de Torres, along with other Dominicans, were responsible for the hard work of bringing together Indian families of many different tongues who lived in scattered, outlying hamlets […] The town of Yantla [Chiantla], which lies at the foot of the mountains, belonged to the [Dominican] Order […] The towns of these mountains, as far as Escuyntenango in the district of Comitlán [Comitán], including Cuchumatlán [Todos Santos Cuchumatán], Güeguëtenango [Huehuetenango], San Martín, Petatán, [and] Güista [San Antonio and Santa Ana Huista] […] were, without doubt, congregated by the Dominican fathers who built in them houses and churches that are still standing today."

(Fray Antonio de Remesal, Historia general de las Indias occidentales, libro tercero, capítulo XIX, Los partidos que en Guatemala administra la Orden de Nuestra Señora de la Merced)

Rabinal: the market

(Diego Valadés, “Didacus Valadés Fecit”, 1579, Rhetorica Christiana)