Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

TWO TEACHERS, JUAN DE HERRERA AND JUAN CORONEL

|

Campeche, 2023, February, meeting of teachers

Schools in Yucatán, XVIth century

Franciscans were convinced that they could eradicate idolatry in Yucatán through education; they founded an important number of elementary schools in the convents of the province. At the beginning of 1547, Friar Luis de Villalpando persuaded Governor Francisco de Montejo that all the Mayan chiefs in Yucatán who so desired could send their children to a monastery school to learn to read and write. The response was immediate: more than a thousand children attended the first school, directed by Friar Juan de Herrera.

Some of the students reached a considerable level of education, especially those mestizos and Indians of the noble class, fluent in several languages: they could read Latin, speak Spanish and write in Mayan language. From this first school came teachers who in turn educated other Indigenous groups in Yucatán towns with monasteries or visitations.

Juan de Herrera

Juan de Herrera, Franciscan lay brother, taught the Christian doctrine and how to read and write in the castellan language, as well as Latin to the Yucatan children. He came to the Yucatan in 1544 or 1545. He had taught before to the children of the West Indies and New Spain. Herrera taught in various churches and convents of the Yucatan: in the school of the Indians of the convent of Valladolid, in the school of the convent of Tekax and in the grammar workshop established in Merida by Bishop Toral. In the year 1563, date of the auto-da-fé of Diego de Landa in Mani, he left Yucatan. After spending a few years in the city of Mexico, he was killed by the Chichimecas Indians, in the north of Mexico, around 1570.

The old San Francisco monastery in Campeche. The Franciscans missioners founded on the Indian ground of Kin Pech, one mile north from the City of San Francisco of Campeche, their first convent in 1546. From the beginning of the Spanish colonization, the Mayan inhabitants of Campeche were kept apart from the Spanish colonizers. They were settled at the entrance to the convent of San Francisco. On the blue column: "This column shows the location where the first mass was celebrated on 1517".

.

The Franciscans open a school in Campeche

"While the Father commissary was busy working on his apostolic mandate in the mountains, Fathers friar Melchor de Benavente and friar Angel Maldonado kept busy in Campeche, studied the Maya language, preached and taught the Indians what little they knew and, with the help of an interpreter explaining what they could not voice themselves, they soon received divine favour and were soon able to speak the language well. Friar Juan de Herrera, while a simple lay friar, was quite smart, wrote very well, sang plain chants and with the organ, and learning the language, was busy teaching the Christian doctrine to the Indians, particularly the children. In order to better achieve his objective, he created a school where all the children came, and their fathers showed good will and pleasure; they said their prayers and he taught many how to read, write and sing: and the Indians respected this knowledge when they saw their children meet that challenge, all the more so as they ignored this knowledge before; only children of the nobles knew the characters used in writing. The work of these early evangelical preachers was very profitable, since thanks to divine favour, the spiritual buildup of so many conversions grew so much that, in less than eight months, they christened all the Indians from the Campeche province who were called Chikin Cheles by the Indians and who numbered more than 20,000 adults, while the number of children was even bigger."

(Diego Lopez de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatan, book 5, chapter 5)

Campeche, September 2024, the church of the convent of Saint-Dominic is being prepared before the patronal feast

The convent of Campeche in 1588

"The convent of Campeche, dedicated to our Father San Francisco, is one of the oldest convents of the province, built of stone and mortar, with its upper and lower cloisters, church, dormitories and cells, but all of it very dilapidated and it leaked and was even falling down. Next to the church is the ramada and chapel of the Indians, in a patio where there are many orange-trees. There is in the convent a good garden and in it many orange, lime, lemon, pomegranate, alligator-pear, zapote, guava, coconut-trees and mameyes de Santo Domingo and some date palms; all this and the garden stuff is irrigated with salty water drawn with an anoria from a kind of pond, a short distance from the sea, in which there live many small mojarras and some turtles. Not far from this pond there is, in the same garden, a well of fresh water good for drinking. The convent is built on the very beach and shore of the sea in such a way that the waves beat on the walls of the refectory. There is at that place a very large and spacious port; however, because of its not being deep, only small boats can enter it. Next to the convent is the town of the Campeche Indians who are about three hundred tribute-payers (tributarios); it is very cool and has many trees, especially orange, guava, coconut, palm, plum and banana-trees, and some that bear a small and delicious fruit called guayas; The people of that town and the four of five others of that guardianía differ as had been said above from the rest of Yucatan in some words, but among themselves they understand each other, and having learned the Maya language, that of Campeche is learned and known with ease, and the reverse. Besides these towns the convent has another three or four of the Maya, all are devoted people and go well-dressed in their fashion.

"A quarter of a league from this convent is a town of Spaniards on the same sea-shore, of eighty residents, of whom some are encomenderos, others merchants, other seamen and boatmen, and there are a few officials; they have a parish priest who administers them the Holy Sacraments, who had also in his charge a barrio called San Roman, of Mexican Indians of those who came with the Spaniards to the conquest of this land. The Father Commissary preached at the request of the local priest to the Spanish residents there in the church of the convent the day after he arrived, and on the Day of the Nativity of Our Lady he preached in an hermitage which is on the same shore between the convent and the town, to which all the people came in procession and with the one sermon and the other, they were very happy and comforted. Three monks were living in the convent; the Father Commissary visited them and remained with them till the 8th of September."

(Antonio de Ciudad Real, Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva España. Capítulo CL. De cómo el padre comisario llegó a Campeche, y de el convento de Xequelchakán, y del de Tixchel y de la Chontalpa,1588)

Campeche, in front of the church of San Roman, meeting to celebrate the promotion of the district as "Pueblo Mágico "(2024, February)

Campeche in 1786

"CAMPECHE, San Francisco de, a town of the province and government of Yucatán in the kingdom of Guatemala, founded by the Captain Francisco de Montejo, in the year 1540. It was originally on the bank of a river, where at present stands the settlement of Tenozic. It was afterwards removed to the river Potonchán, more properly called Champoton; and, lastly, it changed its situation to the banks of the river San Francisco, being notable for the convenience of its port, which is one of the most frequented, and receiving more merchandize than any other in the same gulf. The city is small, defended by three towers, called La Fuerza, San Roman, and San Francisco; and these are well provided with artillery. It has, besides, a parish church, a convent of the order of San Francisco, another of San Juan de Dios, in which is the hospital bearing the title of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios; and, outside of the city, another temple dedicated to St. Roman; to whom particular devotions are paid, and who is a patron saint.

"In this temple there is held in reverence an image of our Saviour, with the same title of San Roman, which, according to a wonderful tradition, began, previous to its being placed here, to effect great miracles; accordingly, it is said, that a certain merchant, named Juan Cano, being commissioned to buy it in Nueva España, in the year 1665, brought it to this place, having made the voyage from the port of Vera Cruz to the port of Campeche in 24 hours. The devotion and confidence manifested with regard to this effigy in this district is truly surprising. There are also two shrines out of the town, the one Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, and the other El Santo Nombre de Jesus, which is the parish church of the Negroes.

"This town had carried on a considerable commerce in the dyeing woods of Campeche, which it used to ship, together with other articles, such as black wax and cotton; but this has greatly fallen off, on account of the distressing invasions that it has experienced. The first of these was by the English, who took and sacked it in the year 1659; afterwards by the pirate Lewis Scott, in 1678; and again by the Flibustiers, in 1685, when the principal fort was burnt and destroyed. It afterwards became a wood inhabited by birds and animals. [In the Maya language, cam signifies serpent, and peche the little insect (acarus) called by the Spaniards garapata, which penetrates the skin, and occasions a smart pain.] Between Campeche and Merida are two very considerable Indian villages, called Xampolan and Equetcecan. The exportation of wax of Yucatán is one of the most lucrative branches of trade. The habitual population of the town is 6000.] Lat. 20°. Long. 90° 25’."

(Antonio de Alcedo, Diccionario geografico-histórico de las Indias Occidentales o América: es a saber: de los Reynos del Peru, Nueva España, Tierra Firme, Chile y Nuevo Reyno de Granada. Madrid, 1786/89)

The Franciscans open another school in Mérida ; the Indians are wary

"The happy Father commissary then asked [1547] all the caciques and important Indians to send their children to town (since he could not be present in all the villages) in order to teach them the Christian doctrine, how to read and write as the Spaniards did, since they already knew that those in Campeche had done so and the benefit they had gotten from such teaching. They replied that they would do so and the Governor sent them away and they went back to their villages. Even though they had given their word, many of them did not follow up, because the devil pushed the pagan priests to convince the children’s parents that it was not to educate them, as the fathers said, but to sacrifice and eat them, or enslave them. As they knew that the fathers interred their dead in the church of the convent, they persuaded many of them that they were witches, that during the day they appeared in the shape that everyone was used to seeing them, but at night they changed into foxes, owls and other animals and that they dug out the bones of the deceased. Since the Indians were confident in the Fathers, they became appalled by such tales and the Fathers lost credit in their eyes. Many of the caciques sent their children, without the hope of seeing them again, and others hid them and sent slaves in their stead. Later on, they were sorry for their actions because those who attended school became good writers, readers and singers and were more skilled than those who stayed at home. They found jobs in the government of their villages, and the children who had been hidden lost all power, as allowed by his divine majesty as punishment for the parents’ spite."

The Franciscans reassure the Indian children

"This erroneous thought, which the pagan priests had instilled in the minds of the Indians was not hidden from the saintly Father Villalpando, and he looked for a remedy to this grave mistake, and discussing ceaselessly and in a saintly way with them, he tried to erase from their minds these lies which they believed in. He spoke to them in such an efficient and conciliatory way that in the end, he assembled more than a thousand children from the town, many of them helped the priests to teach their fellow Indians and became preachers and teachers. The happy friar Juan de Herrera understood these children and put them at ease and showed them love so that they could like the priests, and feel less isolated among these people of a different race, being far away from their parents."

(Diego Lopez de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatan, book 5, chapter 6)

A franciscan teacher (engraving by Francisco Moreno Capdevila, in Joaquín García Icazbalceta, Opúsculos y biografías, Imprenta Universitaria, México, 1942)

Juan de Herrera leaves for the north of Mexico

"After fifteen years of doing such work, it seemed to him that in this province of the saint gospel [central Mexico], he could better employ the gift bestowed to him by God, since there were a lot of people living there. He came to Mexico around the year 1560 and remained in that province for a few years, working and providing a good example, religiously serving the priests who were many at the time and knew well the Indian languages and it was not necessary for them to have the lay friars help them evangelize the Indians. At that time took place the expedition mentioned above, led by the Governor Francisco de Ibarra to the land of the Chichimecas; the provincial man, knowing the spirit of friar Juan de Herrera and his zeal to convert the unfaithful, sent him there with friar Pablo de Acevedo, and they both settled in the village of Zinaloa."

The Chichimecas Indians rebel

"A perverse and mean mulatto lived there, as I said, and he was responsible for the death of friar Pablo by the Indians. He was in charge of collecting the debts that the Indians must pay to their masters and, while doing so, mistreated and upset them greatly. After enduring this mistreatment, all the Indians agreed to kill the mulatto, but were reluctant to kill him while friar Pablo was alive, since they saw that he used him as an interpreter and he made them believe that everything he told them or ordered them came from the priest, who was his chief. After having killed friar Pablo, they threw themselves upon the mulatto and killed him in the presence of friar Juan de Herrera, and with his death he paid for all the misdeed that he had done and the situation he had created, causing the death of friar Pablo."

In front of the school Fray Juan de Herrera, at Herrera del Duque, Badajoz, Spain

They kill Juan de Herrera

"And since an incident is usually followed by a worst one, these fierce homicides, not only happy to have killed friar Pablo and then the mulatto, and aware that if friar Juan remained alive he would testify against their heinous crime, and God would remember their meanness, they were of the opinion that they should also kill friar Juan (even though they held him in high esteem as he was a father to them), they executed their plan and killed him, and at the same time they killed all the Christian Indians and friends whom the Fathers had brought from somewhere else to serve the church and the house. They left the bodies in the fields and took refuge in the mountains where the Chichimecas Indians had their retreat. The Spaniards from around there were apprised of these facts and searched for the bodies in order to bury them, but they had been devoured to the bones by the coyotes and jackals (because in that region they proliferate and are even able to unearth corpses), except for the body of friar Pablo de Acevedo which they found whole and untouched by the animals. But it was so dry and so shrunken that it looked like the body of a child, while alive he was a stout and plump man. My opinion is that our Lord wanted to show that He had kept the body of his servant friar Pablo intact and whole to have his innocence proven, even if it was not as obvious as that of friar Juan de Herrera, whereas the reasons that pushed the Indians to kill him, believing that he was hostile toward them and approved of the mulatto’s harassment, as the mulatto made them understand, etc." Father Torquemada narrates in this way the last days of the happy friar Juan de Herrera.

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatan, book 6, chapter 13)

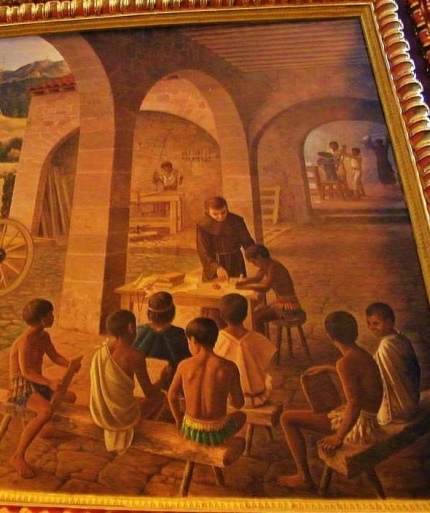

A Franciscans' school (painting in the temple of Guadalupe, Morelia)

"Friar Juan de Herrera, saintly lay friar, of whom I already spoke, was part of the two hundred men that friar Jacobo de Testera brought to Mexico, and of the twenty men who came to Guatemala with the saintly Father friar Toribio de Motolinia, and of the five men whom the saintly apostolic friar Luis de Villalpando brought to Yucatan; even though he was a simple lay friar, he was so ingenious and so saintly, he taught thanks to the former quality and preached inspired by the latter quality. This saintly man taught the Indians how to sing, the first one to put Spanish texts in their hands, to teach them how to read and write, and he taught them catechism in Latin. Afterwards, he worked in such a way as to be able to be ordained priest. He helped a lot with evangelization and was a very saintly man. He was posted in Mexico and from there he accompanied the saintly martyr friar Pablo de Acevedo to Copala where he was going to convert idol worshippers. Once there, he was tortured by the idol worshippers and gave his life for the faith of his Redeemer, after spending twenty-six years in saintly and commendable work and having converted a great number of wild idol worshippers to Christian faith."

(Bernardo de Lizana, Historia de Yucatan y Devocionario de Nuestra Señora de Izamal, 1633, part II, chapter VII, translation: Chantal Burns)

Canek said:

“Luis de Villalpando, Juan de Albalate, Angel Maldonado, Lorenzo de Bienvenida, Melchor de Benavente and Juan de Herrera were the good friars of San Francisco who came to this land long ago to preach goodness and to root out devil. They fought not against the Indians, who received them with innocent souls and gave them welcome in their hearts and in their huts, but against the white men who were hardhearted and deaf to spirit. Let us say the names of these good men like we say a prayer.”

In low voices, the Indians repeated the names: Villalpando, Albalate, Maldonado, Bienvenida, Benavente, Herrera.

Ermilio Abreu Gómez, Canek, History and Legend of a Maya Hero, 1940

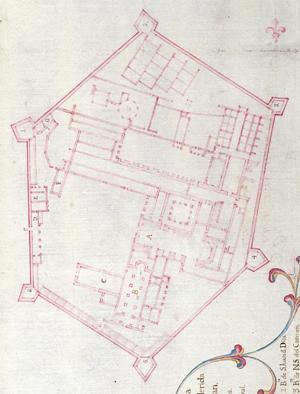

The convent of San Francisco in Mérida (destroyed convent), model in the Museo de la Ciudad of Mérida

The Monastery of St. Francis was erected in the years 1547 to 1600, upon an important Mayan structure, in the eastern part of the city. This convent was the headquarters of the Franciscans in Yucatan, it had two great churches and harboured within its walls no fewer than 200 friars. In 1668, it was enclosed in a fortification, the "ciudadela de San Benito", built for protect the city against the British pirates. In 1820 the Friars were driven out and the citadel used later as a prison. The buildings were destroyed at the end of the XIXth century to give place to the market San Benito.

Juan Coronel

Born 1569, in Spain; died 1651, at Mérida, Mexico. He made his academic studies at the University of Alcalá de Henares, and joined the Franciscans of the province of Castile. He was sent to Yucatán in 1590, and there so familiarized himself with the Maya language that he was able to teach it, the historian Cogulludo being one of his pupils. He wrote a Maya grammar (Arte) that was printed in Mexico in 1620 by Cornelio Adriano César, in the press of Diego Garrido, and of which, however, nothing else was known until the beginning of the XXth century. It was rediscovered in New Orleans by Juan Martínez Hernández who published it in Mérida in 1929. Coronel wrote a cathechism in Maya: "Doctrina cristiana en lengua Maya", which was published at Mexico in 1620, and in the same year there appeared in print, also at Mexico, "Discursos predicables y tratados espirituales en lengua Maya". Father Coronel was one of the foremost teachers of the Indians of Yucatán in the seventeenth century. He was a strict Observant for sixty-seven years, always travelling barefooted. His great austerity impeded his election to the office of Provincial of the Franciscan Order in Yucatán.

Church of Torija, Spain, birth place of Friar Juan Coronel, a slab commemorating him and his brother Francisco. "La villa de Torija a Fray Juan Coronel, misionero franciscano, Fray Francisco Coronel, misionero agustino, 1492-1992"

Juan Coronel educates the Mayas of Yucatan

"The R. and venerable friar Juan de Coronel was from the town of Torrija in Alcarria, and his parents sent him to the university of Alcalá de Henares to study, when God called him to our saintly Order, the saintly habit of which he received in the convent of S. Diego in that town when he was fifteen. Once professed, he came to Yucatan in order to save the Indians. Yet I was not able to determine with which mission he came, whether it was with the one of 1593 led by the Father friar Pablo Maldonado, or with the previous one of 1584. He studied the indigenous language with such regularity that he was able in a short time to preach to them with great ease and eloquence. Once ordained priest (he had become a chorister) he became one of the most zealous ministers of Indian Christianization of that time. God cared for him and we looked up to him, as he ceaselessly insisted that the mission priests coming from Spain learn right away upon arrival the indigenous language with assiduity. To ease their learning, he summed up the grammar and made it simpler and taught it for a long time as he was in charge of that course, and I was one of his disciples when I arrived from Spain and when he left the convent of Mama (of which he was the guardian) to come to the convent of the Mejorada in Merida, to teach us the Maya language. He had his abridged grammar printed in Mexico, a confession manual, a handbook of all the Christian doctrine and a book on spiritual talks, all of them in the Indian language."

Merida, Mejorada monastery (2024, September)

He behaves like a saint

"He was a very observant and exemplary priest, a recluse, who came out of the mission convents only to give the sacraments to the Indians, and when he lived in Mérida, only rarely and for religious business. He was so chaste that never he was heard saying anything contrary to the purity of such virtue. He never wore fine fabrics, except for his underwear, walked barefoot until old age and ailments forced him to wear shoes, and for years he suffered from a bad fracture that put his life on the line. I saw several times the flesh coming out of his wound to such an extreme that we doubted we could put it back in place, and he endured his suffering with remarkable patience. He loved his saintly poverty, but with discretion since as he was the guardian, he could not appear miserable, tending as necessary to the needs of his subordinates, although he restricted himself as if he were very poor."

Merida, demonstration for the climate in the district of la Mejorada (2021, August)

He refuses all promotions

"In all the convents where he was a guardian, he cared greatly about the divine ornament, and improved greatly the sacristies. He was a guardian several times and a definer of the province, but he was not able to become provincial as he seemed too rigid, when in truth he was very zealous about monastic observance and wished that it would be preserved with the flourishing integrity it had when he came a long time ago, and which allowed this province to be renamed with a saintly name. During the celebration of the chapter in 1655, he withdrew in the convent of Merida since his infirmities did not allow him anymore to be useful to the Indians, but he preached there to the Indians of San Cristobal (who are under our administration) as often as he could. Although he retired and had no intention of accepting any other assignment, his obedience made him accept the post of guardian of the convent of strict observance of the Mejorada, on the occasion of the congregation of 1636. But as soon as he could, he went back to his primary wish to recommend himself to God in the quiet role of subsidiary. He was again interrupted by the vacancy of the post of guardian in the convent where he stayed, and was appointed Chief guardian. He then requested to be exonerated from this task in order to remain quietly in his cell."

He dies as a mystic in the convent of Mérida

"He lived there until the year 1651, suffering from several diseases almost all of the time, which forced him to stay in bed, but without using any sheets, except cotton covers which he used as sheets. He accepted all his maladies with patience and submission to the divine will. At that time, I heard him as penitent, heard his confession, and I never entered his cell (as I often visited him) without finding him reading a book of worship, or praying, or seemingly in contemplation with such a noble face and his eyes up to the sky even though he was in bed, and I was able to discover him in such a state as he was somewhat deaf and did not hear me when I came in. His diseases progressed and after receiving the Sacraments with much devotion, he went to eternal life on 14 January 1651, and he was buried in the convent of Mérida, leaving behind him the reputation of a perfect being totally respected by people of all strata of the society. He lived until the age of 82, of which 67 years were devoted to religion, sixty-two years in the province, and more than forty-eight years ceaselessly devoted to teaching the Christian doctrine to the Indians."

(Diego Lopez de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatan, book 12, chapter 18, translation: Chantal Burns)

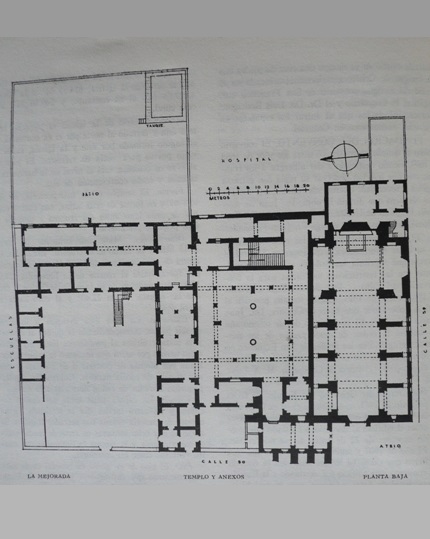

Map of the convent of la Mejorada (Catálogo de construcciones religiosas del estado de Yucatán, Recopilación de Justino Fernández, Talleres gráficos de la nación, México, 1945)

The convent of the Mejorada in Mérida

“We have in the town of Mérida another convent called the Mejorada. Its founder was D. Diego Garcia de Montalvo, who wanted to use it as a retreat and gave the land for its construction. The Fathers who knew the country were opposed to this idea, and warned him of the difficulties ahead, today proven, that would represent the maintenance of the convent in such a small town, as there already was another convent there. It would be an additional burden for the superiors to find persons to tend to it and indeed, it was, when the priority was to ensure the evangelization of the Indians, in a province where there were few priests […]

"The church has a modern appearance. It is one of the most beautiful and impressive churches in our region. It has a large transept in front of the altar, covered with a half moon cupola, above which is a lantern used as keystone. The building itself has on each side four vaulted chapels facing each other, with beautiful altars surrounded by superb golden gates. The tribune and the cupola of the apse are covered with frescoes, remarkable paintings by the same master who painted in the main convent of Mérida. The altarpiece of the main altar is a sculpture in the Doric style that covers a whole section of the wall of the main chapel. The decorations of the sacristy altars go beyond anything we have in our country and could look stunning in richer countries. All those who see them cannot but approve and admire the manner in which the Father friar Pedro Navarro spent so much money. When he visited that church last year, in 1655, D. Francisco de Bazan, who had just arrived to be the governor of our country, said : "I feel as if I were seeing the church of doña Maria de Aragon in Madrid."

"On 22 January 1640, the sacraments were set up inside it, with great fanfare and the help of the inhabitants of the town. Preaching was conducted during the Octave of its consecration. To commemorate this event and in order not to forget it, an engraved marble plaque was affixed inside the door leading to the cloister; it reads "In the year 1640, on 22 January, this church of the Dormition of our Lady was dedicated, the pope being Urbano VIII, Philip the Fourth being king of all Spain and friar Juan Merinero being general of the whole (Franciscan) Order."

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatan, Book 4, Chapter XIV, Del hospital de San Juan de Dios: de nuestro convento de la Mejorada y otras hermitas, translation: Chantal Burns)

A Franciscan teacher in central Mexico, Fray Pedro de Gante (statue in Mexico city, Plaza Fray Pedro de Gante, sculptor Albert Desmedt, 1976)

"New Spain’s first and only seminar for every kind of trades and crafts […] was the chapel called San José, where the most venerable servant of the Lord and famous brother Fray Pedro de Gante lived for many years; he was first and foremost a teacher and an industrious tutor of Indians. He endeavored to have the older boys learn the Spaniards’ trades and arts, which their parents did not know, and improve those that were used before. For this purpose, at the back of that chapel, he set up some rooms where the Indians were gathered, and he had them first practice the most common trades, such as that of tailor, carpenter, painter, and others of the kind, and, afterwards, more sophisticated vocations […] in that way, and before long, many more [Indians] than our officials would have liked had learned these trades. Some enterprising craftsmen, newly arrived from Spain, had at first a monopoly, but the Indians very soon upset them with their patent astuteness, their ingenuity and quest for perfection."

(Jerónimo de Mendieta. Libro cuarto de la historia eclesiástica indiana, Capítulo XIII, De cómo los indios aprendieron los oficios mecánicos que ignoraban, y se perficionaron en los que de antes usaban)

|

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

The convent of San Roque or San Francisquito in Campeche during the walking tour "Vive La Leyenda" in the city centre, 2019, December

The San Francisquito Convent (San Roque) is today the Cultural Institute of Campeche. It was built in the 1700s as a refuge for friars whose monastery to the north was threatened by pirates. The church safeguards a beautiful altarpiece of Salomon columns, the predominant style of late baroque in Mexico after 1740. The Cultural Institute was once the Franciscan Hospital of San Roque.

The most celebrated Franciscan school for Indians in the XVIth century: the Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in Mexico City

Monastic Orders in Latin America today: The Colegio Motolinia in Mérida, Yucatán

Map of the citadel of San Benito in Mérida "Plano de la Ciudadela de Mérida de Yucathán" Archivo General de Indias (Sevilla, España, 1751)

“The citadel, or castle, stands on a level spot of ground (as the country is in general); as you enter the town, from the eastward, it is of no consequence, being originally built to protect the Friars from the insolence of the natives: it at present incloses a monastery of the Franciscans beforementioned; it is in form a hexagon, with salient angles; with light pieces about four and six pounders mounted, some brass, some iron. The wall about ten yards high, has no ditch, or out-work. […]; 'tis by no means in a condition to defend itself against any foreign enemy that have artillery.”

(Remarks on a passage from the river Balise, in the bay of Honduras, to Merida, the capital of the province of Jucatan, in the Spanish West Indies, by Lieutenant Cook, in February and March 1765.)

A courtyard in the Franciscan convent of La Mejorada in Mérida. The convent building served at different times as a women’s jail and a soldier’s barracks, and in 1970 was donated by the State government to the Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (UADY) and now houses the School of Architecture

The nave of the church of La Mejorada