Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

DOMINGO DE VICO, DOMINICAN MARTYR

|

The martyr of Fray Domingo de Vico

The statue of Domingo de Vico, on the façade of Santo Domingo church, Rosary Basilica, in Guatemala City

In 1555, despite many reports of unrest among the Christian Acalan of San Marcos, Domingo de Vico, Prior of Cobán, accompanied by a young Dominican, Fray Andrés López, returned on a mission to the village.

The location of this village is uncertain, may be somewhere west of the present village of Chisec. The province of Acalan was a poorly defined area north or northwest of Coban, Alta Verapaz. The people are sometimes called Acalan or Acala, but more frequently are referred to as Lacandon. Many were baptised, and these were gathered in San Marcos.

Don Juan Matalbatz, Indian Governor of Alta Verapaz, tried without success to persuade Fray Vico to allow him and a band of three hundred Christian Indians to serve as escort. Apparently the non-converted, angered by fear of encroachments of Spanish rule, revolted, and with the aid of a group described as neighbouring Lacandon, but almost certainly fellow Acalan, murdered the two Dominicans, captured and sacrificed on the spot a young acolyte, and slew some thirty of the Christians Indians from Alta Verapaz who had accompanied the father.

Domingo de Vico and Andrés López set out for Acalá

"The

devil took possession of the hearts of some of the principal idolaters of

the province of Acalá who were not well grounded in the faith and good

habits they had been taught. They tried to destroy that first village, which

was the gateway for the priests to others, and served as headquarters for

what was necessary for the conversion of the others. They also plotted to

kill Father Fray Domingo de Vico, and to bring this about they got together

with the Indian leaders of the province of Lacandón. […]

After preparing for the trip with long vigils, prayers, and fasts witch the

community offered to God for its successful outcome, and having the Indians

and supplies ready for travel, Father Fray Domingo de Vico chose as his

companion Friar Andrés López, a native of Castillo de Garcí Muñoz, in Spain,

son of Pedro Moreno y Ana López. He was

strong and

robust, the bravest of the brave, and stronger than any other Spaniard in

the Indies, as the alcaldes and half the population of Ciudad Real (San

Cristóbal de Las Casas) could bear witnesss, for all of them were unable to

take him prisoner in certain knife fights which he had there with a

neighbour. After having been one of

the most adventuresome soldiers in Guatemala, he took the habit of Saint

Dominic in the convent of Santo Domingo of Guatemala, on april, 24, 1551,

and had been at the convent in Cobán only a short time. The two priests,

firmly resigned to the will of God, set out with their Indians for the

province of Acalá."

Statue of Don Juan Matalbatz, by Rodolfo Galeotti Torres, in San Juan Chamelco, Alta Verapaz (Guatemala)

The life of Don Juan Matalbatz, by the people of San Juan Chamelco

"I collected narratives of Aj Pop B’atz’ from more than twenty Chamelqueños of different ages, religions, and educational backgrounds. According to the stories I collected, the exact birthplace of Aj Pop B’atz’ remains unknown. Following the Spanish abduction of the region’s former leader, a council of elders elected Aj Pop B’atz’ king of Tezulutlan, now Alta and Baja Verapaz, based on his wisdom, bravery, faithfulness, skill, and prudence. As king, he prepared his forces to resist the inevitable Spanish invasion and invoked his supernatural powers to ask the tzuultaq’a to keep the Spaniards away.

Nevertheless, as time went on, Aj Pop B’atz’ found the Spanish invasion inevitable and, rather than risking the slaughter of his people, he welcomed the Spanish peacefully to his home. Following a meeting with Dominican priests, Aj Pop B’atz’ became the region’s first Catholic, accepting baptism in a nearby river.

His cooperation with the Spaniards’ colonization efforts led them to take him to Spain to meet King Carlos V in 1544. Aj Pop B’atz’ took with him on his journey gifts native to the region with him, including quetzal feathers, birds, and textiles. Aj Pop B’atz’ arrived at the palace during the night to find the King asleep. He lined the throne room with his gifts and awaited the King. The next morning, the Spanish king woke to the songs of the birds and asked to meet the man who had delivered them. When Aj Pop B’atz’ was presented to the King, he refused to bow to him despite court tradition. […]

Aj Pop B’atz’s refusal to follow court traditions led King Carlos V to admire his strength. Respecting his position as an indigenous king, he gave Aj Pop B’atz’ silver crosses, incense burners, and three silver bells for Chamelco’s church. King Carlos V designated Chamelco a pueblo de indios ‘‘independent Indian town,’’ giving it autonomy in governance throughout the colonial period. In 1555, he named Chamelco a royal city of the Spanish crown and designated Aj Pop B’atz’ ‘‘Lifelong Governor’’ of Guatemala’s Verapaz region. […]

Arriving once again in Chamelco, Aj Pop B’atz’ assisted the Spaniards’ efforts to spread Catholicism and settle the town center. He organized the town’s central neighborhoods, still recognized today. The Spaniards overseeing the development of Chamelco ordered Aj Pop B’atz’ to assist them in building the town’s first Catholic Church. Chamelqueños recall that he used his supernatural powers to build the church in one night, whistling the construction materials into place. […]

Aj Pop B’atz’s eventual fate remains unclear for most Chamelqueños. Many state that he spent his final days overcome with shame, seeing the changes that Spanish had brought to his town. Others state that the Spaniards, envious of his power, turned against Aj Pop B’atz’. In either case, he was treated to a cave in Chamil, where he died. His spirit, Chamelqueños say, protects the town from natural disasters and from the violence of the civil war."

S

arah Ashley Kistler, Writing about Aj Pop B'atz', Rolling College, 2015

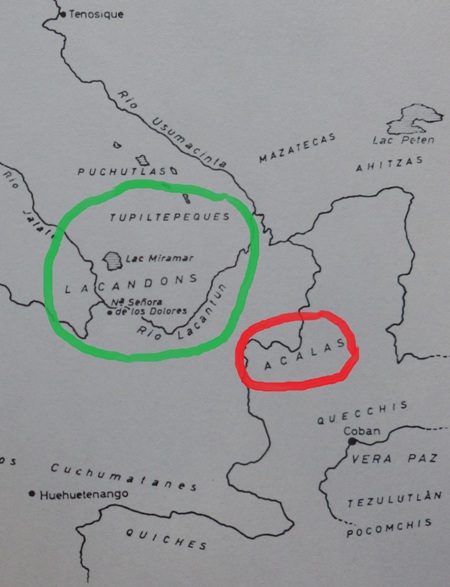

The location of the Acala of San Marcos? A localization in André Saint-Lu, Las Casas indigéniste, études sur la vie et l'oeuvre du défenseur des indiens, L'Harmattan, Paris, 1982

Don Juan tries to protect the two religious

"The Indian Don Juan, Governor of all the province of Verapaz, went out to meet him on the road and strongly plead with him to return to Cobán and not continue onward, because he was sure they were going to kill him in Acalá. Father Fray Domingo would not be dissuaded; rather, confiding in God, he continued his journey, heedless of Don Juan’s affectionate importunity. This admirable Indian, never sufficiently praised for his great Christianity and ardent zeal, gathered more than three hundred soldiers and returned with them to accompany the prior, who begged him to return and let him continue on with his own Indians. The most the prior could get him to agree was to take his men by another route and let the two priests proceed alone through the villages, preaching and appealing to those who had converted. The conspirators had their men and the Lacandónes ready, but when they saw the chieftain Don Juan, and heard about the men he had brought, they disguised their treason and hid the Lacandónes in the mountains"

Juan Matalbatz, Guatemalan stamp, 2014

Domingo de Vico orders Don Juan to leave

"When Father Fray Domingo arrived at the Christian village of Acalá, not seeing any signs of treason, he assumed the news was false, especially since he had expected to find the Indians banded together and armed. Considering that Don Juan’s army had no supplies because they had not looted the land, and as the Indians, to conceal their evil intentions, assured him they wanted to be Christians, and thinking they and others hadn’t gathered at the church out of fear of the chief and his men, Father Domingo ordered Don Juan to leave and take his men with him. The chieftain replied that the Father should think carefully about his command, because he was certain that as soon as he left those Indians would kill him. The chief could find no way to make the prior change his mind, thereby prophesying what was going to happen. Finally, with great insistence and then commands, the priest ordered him to leave and he had to obey, much against his will. After staying three more days Don Juan headed home with the men he had brought, leaving Fray Domingo, his companion, and the Indians they had brought with them alone in the village, and a few others that he left behind. In order to reassure the natives of that province and remove any misgivings, and oblige them to go to the church, Father Fray Domingo disarmed the Indians of Cobán who had stayed with him, taking them away all their swords and shields."

The Indians of Acalá rebel

"The wounded spirit of those perverse men wanted nothing more than to see themselves in control of the settlement. Immediately they began to shout, take up arms, and call the Lacandones. In less than an hour they were all gathered in the village, screaming loudly, all traces of obedience and respect gone. Father Fray Domingo, watching this, and knowing for certain what he had long been warned about, withdrew with his companion to a house they had there, and spent the night in prayer. Near dawn, seeing all the Indians quiet, Friar Andrés asked the prior for permission to leave and rest for a while. He replied that it was a good time to do so, but that he would remain there to pray. As dawn was breaking, a brave Cobán Indian came to the door of the house and shouted: “Father, the house is on fire, though it burns slowly because the leaves are green; but it will eventually go and you will have to leave it if you don’t want to be burned alive. Give me the sword you took from me which is under your bed, and come with me, and I will give you my word I will get you and Friar Andrés out of here and free you from more than a thousand Indians who are waiting for you.” The priest told him that he must free himself, and that if God wished, he and his companion would be saved by Him. The Indian tried a second and a third time, and finally the prior gave him a sword and shield, saying, “Take this and free yourself, and go back to your land.” With the shield on his arm and the sword unsheathed, like a lion on the loose he broke through the middle of the rebel force, a rain of arrows falling on him. He finally got away, wounded by some of the arrows, though not very seriously."

The martyrdom of several religious killed by Indian archers, in Historia Eclesiástica Indiana, by Gerónimo de Mendieta (1596)

Domingo de Vico is fatally injured by the Indians

"When daylight came Father Fray Domingo went down the steps that led to the plaza where the Indians were and walked through their midst, preaching. For some time the Indians made way without approaching him, because they had the pagan superstition that if they got too near a priest they would die afterwards. That did not stop the multitude from shooting at him, although no arrow wounded him at that moment. Having entered the church, he knelt down and fervently commended himself to God, praying for the conversion and enlightenment of those blind idolaters. Seeing that the church was afire and the roof was falling, he went back outside among the Indians and asked them in a loud voice what evil he had done to them and why they wanted to kill him. The answer was a rain of arrows which fell fast and furiously. One of them hit him in the throat, and feeling the wound, he cried out “Jesus!” in a loud voice and fell to the ground. At that moment Friar Andrés woke up, and going to see what happened, as he walked out the door of the house an Indian shot an arrow at him which stuck in his beard. He lost a lot of blood but he merely yanked out the arrow with one hand and wiped the blood with the other, and ran full speed to help his beloved companion who was bleeding from his terrible wound. Taking him up in his arms with the help of two acolytes who were with Father Fray Domingo, and defending himself with his cloak and scapular from the arrows falling around them, they carried him to the house; bracing him against the wall, Father Andrés, on his knees, attended him at his moment of death, even though he himself was bleeding a great deal from his wound."

Murder of a Franciscan friar during the 1680 Pueblo revolt

An Indian boy tries to save the two friars

"The idolatrous barbarians did not stop pouring arrows on them, even though one was dying and the other near death. One of the Indian acolytes, with a shield he happened to find, protected them from the arrows. One of the Lacandón leaders shouted out angrily, “Is there no one who will dare to go there and bring me that boy who is foiling our attempts?” One who had more courage than the others (not because there was either defence or offence on the part of the priests to fear, but because of the superstition of evading the priests to avoid death) knocked down the acolyte and took him to the archers, who immediately tore open his chest and took out his heart, sacrificing him and offering it to the sun which the Lacandones and Acaláns adored as their god. Proud of this sacrifice, the idolaters stopped shooting and a large group of them went to kill the horses so the Christian Indians whom the priests had brought and whom Don Juan had left -who were still alive, although some of them had already died- would not escape. Meanwhile, father Fray Domingo de Vico died, offering his life as a sacrifice and in thanksgiving for the immense favour of such a death, on Friday, at seven o'clock in the morning, eve of glorious Saint Andrew’s day."

Orozco's painting, "Cabeza flechada" (Head shot through with arrows, 1947), showed at National Museum of Art in Mexico, exhibition "Constellations of memory. Stories and counter stories of the conquest", 2021, November

Andrés López also is killed by the Indians

"When Friar Andrés López saw that he had died, and that the Indian archers had stopped shooting, he rose and went to his room, which was not yet on fire, and taking his breviary and a little corn in a cloth, praying and commending himself to God, he left and started out on the road to Cobán, though still bleeding from the wound he had received. He had gone only a short distance when he met a large group of idolaters who filled him so full of arrows he looked like a porcupine as he fell dead on the road. Those cruel barbarians did the same thing to thirty other Indians who had stayed, and who had not extricated themselves and were fleeing along the Cobán road."

(Fray Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, Book 10, Chapter 7)

Four years later,

in 1559, Don Juan, the Indian governor, and

a Spanish

force entering from Comitan, led

an expedition against the Acalan

to revenge the deaths

of Fray

Domingo de Vico and his companion Fray Andrés López.

The Indian

leaders supposed

to have been involved

in the deaths

of the friars were hung, and

180 prisoners were taken. The

royal decree sanctioning these

invasions had declared that prisoners should be sold

as slaves.

The

intercession of the fathers stopped this killing and punishment

of the Indians. Since their own

lands were

a three-day journey from the other Christians, they brought them

to the

city of Cobán. Here they remained, although against their will.

These events put

an end

to the experience of Verapaz peaceful

evangelization, undertaken

by Bartolomé de Las Casas.*

* Refer to Juan José

Guerrero Pérez's essay: De Castilla y León a Tezulutlán-Verapaz. La sobrehumana

tarea de construir un país autónomo en el Nuevo Mundo del siglo XVI.

Guatemala, F&G Editores, 2007.

A Lacandon, "the priest", by Raúl Anguiano, in Expedición a Bonampak, Diario de un viaje, Instituto de Investigaciones estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Imprenta Universitaria, 1959.

The punishment of those of San Marcos

"The ruler, who we said was of San Juan, when he returned [home], feared for [the friars] and sent some Indians to see the prior and learn how he was. They found on the road the alarming spectacle of Father Friar Andre. Returning from their confrontation, they advised him of the disgusting find left by the enemy Indians. Some Spaniards in the entourage of the Spanish governor of the Verapaz followed the trail of those of San Marcos and arrived at the site, where they found the mutilated body of Friar Domingo without [his] head and they sent it to the convent. All the fathers came to receive it and greeted it with many tears. They buried their bodies before the major altar of the church of Cobán.

"Continuing in the pursuit, the Spaniards captured many Indians, suspended them from trees, and killed them from below with arrows. The incident, and the fear of punishment, depopulated all these lands of San Marcos. […] We saw the old sites of the settlements that were there before the death of Friar Domingo; and even after many years, columns of the church, the altars, and the stairs of the high altar were still standing at the site of those of San Marcos."

(Friar Gabriel Salazar, “Brief description of the Manché: the roads, towns, lands, and inhabitants”, 1620; translated by Lawrence H. Feldman, in “Lost shores, forgotten peoples: Spanish explorations of the South East Maya Lowlands”, Duke University Press, Durham, 2000.)

Ocosingo, Chiapas, Lacandon monument. The present Lacandon are not the direct descendants of the Indians responsible for Domingo de Vico's death. They migrated from the Yucatan peninsula to the rainforest during the XVIIth century to escape the Spanish

Juan de Villagutierre:

"When Don Juan Cacique, Governor of Verapaz, found out about the cruel barbarity of the idolators he took upon himself the revenge of the two religious' deaths, and [...] he stated publicly, and especially to the priests of the Santo Domingo convent in Cobán, that his heart would not rest, nor would he find any respite, until he had rooted out all the Acaláns and Lacandones in satisfaction and revenge for the deaths of Prior Domingo de Vico and Fray Andrés López, his companion, so great was the love he had for the prior, and so great was the sorrow he felt over the treacherous fate dealt by those barbarians.

"The Dominican religious of Chiapas silenced all that was being said, but informed the Council of the Indies of the Lacandón atrocities, because they did not want it to appear that they were motivated by personal interests to revenge, especially over the deaths of the prior and his companion, but rather for the common good and Christian peace of those provinces, and the ending of evils, robberies, and sacrileges that those barbarians, pagans, and apostates were constantly commiting - destroying villages, burning churches, despoiling images, venerating idols, sacrificing children, profaning altars, capturing Christians and forcing converted Indians to apostatize - all kinds of crimes and evil, horrible, and detestable sins."

(Juan de Villagutierre Soto Mayor, Historia de la conquista de Itzá, 1701, Book 1, Chapter 10)

Today, several families in Lacandon Maya communities have become tourism entrepreneurs. Here, a Lacandon guide in the ruins of Bonampak

The miraculous (and illusory) conversion of the Acala Indians

of San Marcos

"While

the religious walked towards Acala, the Indians were conducting a very

solemn sacrifice to the principal god of their land. The man who was to be

sacrificed was present, and the blade was about to strike him to cut out his

heart. The demon began to speak from the mouth of the idol, saying: Stop,

stop. Sacrifice to us no more, now that our time has passed, and our days

has over. So awestruck were the Indians by these words that they let the

man go, and waiting for something else to happen they did nothing else. It

was then that the fathers arrived, and Friar Domingo de Vico preached the

faith to them with much spirit, and as always in these sermons condemned the

adoration of the idols and the sacrifices they made, particularly the

inhumanity of sacrificing men. They were told what happened with the idol a

few days before they arrived. The fathers were impressed, and added to this

similar stories from other priests.

"Father Domingo

de Vico was quite successful with his sermons, and Our Lord favored the

Naturals with his grace and many of them received the faith, and gave up the

idols with all of their hearts, and they collected a great number of them,

and they publicly burned them."

(

Cobán, 2023, September, police in San Marcos district. After the murder of Friar Domingo de Vico, the Domicans brought the Acalá Indians of the village of San Marcos to that place.

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

Cobán: Convent of Santo Domingo de Guzmán and cathedral, starting point for Domingo de Vico (these buildings date from his time, the cathedral undertaken by Fray Melchor de Los Reyes in 1543, the convent by Fray Francisco de Viana en 1551; the cathedral had to be rebuilt in 1741, 1799 and 1965, because of successive earthquakes

Instituto agroecológico Fray Domingo de Vico, funded in Santa Maria Cahabón, Alta Verapaz, by the Dominicans

Domingo de Vico (1485-1555), a manuscript of "Teologia Indorum en lengua quiche"

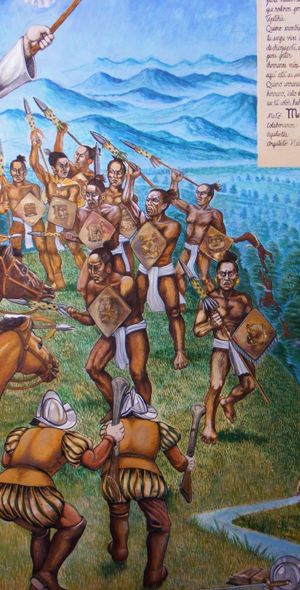

An Indian resistance, fresco by Manuel Suasnávar Pastrana, 1988, Palacio de Gobierno, Comitán, Chiapas

By the turn of the eighteenth century, Dominican Friar Francisco Ximénez,

wrote that the majority of Domingo de Vico’s works could still be found among the Mayan leaders:

"[I]t is a lot to note those first fathers that wrote, who at least some writings can still be found, those of the venerable father [Vico] have not all been lost, whereas before only some of his are saved by the Indians, holding on to them with a veneration as if it was a rich treasure; reading publically in the church on the days which they gather, and it is a very dignified thing I recall that there are some very obscure old writings that today that seem to have been updated a great deal from the ancient languages as in every successful language, of this venerable father [Vico] they are clear for all that appear in the same language that is found today".

(Francisco Ximénez, Historia de la Provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la Orden de Predicadores, circa 1701)