Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

walls

|

BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS AGAINST THE CONQUISTADORES

|

In 1544, at age 70, Bartolomé de las Casas was appointed Bishop of Chiapas, in order to enforce the New Laws of the Indies ("Laws and ordinances newly made by His Majesty for the government of the Indies and good treatment and preservation of the Indians", 1542).

Coming in Ciudad Real [San Cristóbal de las Casas], he got in trouble here when he preached against slave holding and forbade his priests to grant absolution to any slaveholders, unless they gave up their slaves. Las Casas not only faced opposition from the colonists, but his own clergy refused to follow his orders.

The planters wanted to keep their slaves and threatened to kill their bishop if he continued to demand their release. Things got so bad Las Casas went to the Audiencia de los Confines in Gracias a Dios but the president of the Audiencia called him a “lunatic,” and didn’t really help him.

In 1547, Bartolomé de las Casas was forced to flee in fear of his life. He never returned to the Americas.

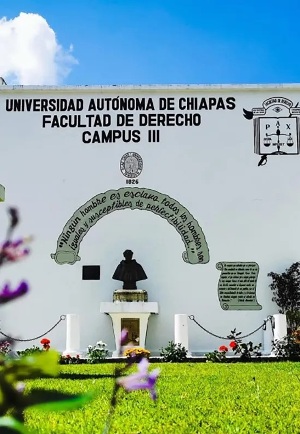

A statue of Bartolome de Las Casas in San Cristobal de Las Casas

Antonio de Remesal, our principal source about the life of Bartolomé de las Casas, relates these events:

Mayan Indians are enslaved

"[…] In the first days he was greatly affected by the trade in Indian slaves who were bought and sold like sheep to work in the fields and mines, to carry loads or work like animals and frequently treated with little compassion. This was, of course, common practice in all the Indies, and the residents of Ciudad Real did not sin any more than those of Mexico and Guatemala. Since Bartolomé de Las Casas was not responsible to God for all the sinners in the New World but only for those in his own care, he wept for them. That was much worse when a small Indian girl came to him, secretly from her masters, and said: “Father and great Master! Make me free! Look at me, I don’t bear on my face the mark of slavery, however my master bought me as a slave. Please defend me, you, my father!” And she might add a great many other words to express her grievances most vividly. […]"

Bartolomé de Las Casas refuses to absolve the Spaniards who own Indian slaves

"But it was not all words! On Lazarus Day and Passion Sunday he deprived all the confessors of the town of the right to hear confessions! From this he expected the Dean and the canon of the cathedral, but he handed them a memorandum, listing the cases he reserved for himself. The reason for restricting the number of confessors was his doubt of their adequacy and fitness for the task. […]

"When the confessions began, the two confessors refused to absolve anybody

who did not follow his commands on Indians serfdom and slavery, declared it

a special case and referred it to the Bishop. People became confused when

they saw themselves deprived of the sacraments, something which had never

happened to them; since anyone of them thought to lead a sinful life,

keeping slaves and buying and selling them. They said no Indian would any

longer do what a Spaniard ordered him to do. Practically all had their

material interests at heart and the advantages derived from the enslavement

of the Indians. If it ceased, profits from sugar would suffer and so would

that from the corn production and the gold and silver mines. Money would no

longer flow into their doffers, and pure chases and sales would shrink. They

placed these considerations above the demands of divine law, remained

adamant in maintaining the status quo, whatever the Bishop said. Let him do

what he fancies! […]"

Conquistadores and religious, reconstitution at De Soto National Memorial in Florida

The Spanish colonists complain of Las Casas

"The opposition quoted the papal bull conferring upon Castile the right to the Indies, pointing out that upon this holy document rested their right of conquest; they did not see any sin in enslaving the enemy in a just war. Las Casas replied that he had read all the papal bulls and had never found in them a single word, authorizing war or slave holding, and that the Pope had no power to tell him to grant absolution to those who sinfully kept Indians in servitude and continued in sinful behavior. This reply did not prevent them from saying the bishop disobeyed the commands of the Holy Father and ignored apostolic brieves.

The colonists addressed to the Bishop, a formal "requirement" drawn up by a

notary public, containing arguments to support their claims, based on the

terms of the Bull of Alexander VI, and threatening, if he persisted in

refusing them the sacraments, to appeal to his metropolitan, the Archbishop

of Mexico, and ultimately to the Pope: meanwhile they would denounce him to

the King and his Council as a disturber of the public peace and a fomenter

of dissensions and troubles in the country. To this threat the Bishop

answered: "O blind men! How completely does the devil deceive you! Wherefore

do you threaten me with your complaints to the Archbishop, to the Pope, and

to the King? Know then that though I am obliged by the law of God to do as I

do, and you to obey what I tell you, you are likewise constrained there unto

by the most just laws of your sovereign, since you think yourselves such

faithful vassals to him."

Drawing then forth the new laws, he read to them the statutes relating to

Indian slavery and continued. "Not you of me, but I have a right to complain

to the king of you, who do not obey his laws." The spokesman of the city

answered that a protest against those laws had been sent to the king, and

that therefore they should be allowed to remain in abeyance until he should

have accepted or rejected their remonstrances. The bishop retorted: "Your

argument would hold good, were not these laws founded on the laws of God,

and were it not an act of natural justice to set free these Indians, who

have been tyrannically enslaved." The situation was a deadlock, for the

Bishop was immovable, neither would the Spaniards give way."

(Fray Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 6, chapter 2)

Pope Paulo III 's Bull nominating Friar Bartolomé de las Casas bishop of Chiapas, Rome, 1543, december 19, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla

The Dean of San Cristobal de Las Casas deceives his bishop

"On Palm Sunday, Easter Thursday, Sunday and Monday, the Dean admitted to holy communion various persons who not only continued to hold their Indians in spite of the Bishop's remonstrances and admonitions, but were notoriously engaged at that very time in buying and selling slaves. […] This annoyed the Bishop greatly, and he ordered his arrest and sent his alguacil and some of the clergy to bring the recalcitrant Dean before him. […]

"The comings and goings of messengers had attracted the attention of the citizens. The news of what was passing had spread through the town and a crowd of people had collected to see the Dean’s arrest. The appearance of the Dean, being conducted by force to answer to the Bishop for disobedience, provoked a demonstration in his favor. He, seeing his opportunity, began to call for help, crying: "Help me to get free, gentlemen, and I'll confess everybody! Get me free and I'll absolve all of you!"

"An alcalde began to shout: "Help in the king’s name! Help in the king’s name! Place to the justice!" By now the news of the arrest had reached everybody in the city, and the residents, fully armed, converged upon the street which began to look like a battlefield in the border. Some even tried to barricade the Dominicans’ residence to prevent from coming out to support the Bishop; others tried to free the Dean from his captors, and indeed, they did succeed and managed to conceal him. Thus, with great uproar, shouting: "Long live the king!" the mob arrived at the Bishop's house, into which a crowd forced its way with clamorous disorder.

Father fray Domingo de Medinilla and Gonzalo Rodríguez de Villafuente, a gentleman of Salamanca and resident of Villa Real, were in the ante-chamber, and they managed to somewhat calm the people. The Bishop heard the voices and left his room to speak to the intruders. Father fray Domingo, however, pushed him back into his room, but the door could not be locked. The ringleaders entered the Bishop’s room. Much argument ensued, and the man who had fired the harquebus swore he would kill him. A great deal of heat was generated in this encounter, but the storm of popular fury broke itself against the imperturbable serenity and inflexible determination with which Las Casas met and dominated it, and they left. […]"

(Fray Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 6, chapter 3)

San Cristobal de Las Casas, 1992, october 12, destruction of the statue of Diego de Mazariegos, Chiapas conquistador, in front of the Dominican Convent

Expelled from the city, Las Casas comes back secretly

"[…] The Bishop traveled throughout the night, entered the city unnoticed at dawn, and as he had no other place to rest, he went straight to the cathedral. […] So the alcaldes and regidores went to the cathedral, accompanied by all the residents. They seated themselves as though for a sermon. When the Bishop entered from the sacristy to speak to them, nobody asked for his blessing, no one rose or showed any of the customary marks of respect. The town notary rose and immediately read the "requirement" it had been their intention to present before Las Casas was admitted to the city, in which they suggested how the Bishop should behave, how he should treat them as individuals and persons of quality, that he should help them to keep their estates; if he did this, they would accept him as their bishop and obey him as their rightful shepherd. […]"

A violent quarrel into the cathedral of San Cristóbal de Las Casas

"While the Bishop expressed his saintly views, trying to reach the souls of the men of Ciudad Real, Satan sowed discord by means of the imprudence of a regidor, who, from his seat and without standing up nor taking off his cap, said to the Bishop that he should know how fortunate he was in having as his sheep such leading gentlemen as those in front of him; that they greatly resented not being treated with the proper respect due to them and that they had every right to object to the way he dealt with them. The manner in which he had called them was not the way to treat the representatives of a famous city. He should go back to his quarters and return whenever they, the magistrates, called him and then explain himself.

The Bishop listened to everything the regidor said most attentively; he

realized that his own position was by no means strong; he took Moses as his

model, who had been gentle and pacific when facing a threatening multitude

but who also knew how and when to draw the sword when idolaters closed in on

him. With the authority which was his, he said to them: “Look you, sir,—and

all of you in whose name he has spoken,—when I wish to ask anything from

your estates, I will go to your houses to speak with you; but when I have to

speak with you concerning God's service and what touches your souls and

consciences, it is for me to send and call you to come to wherever I may be,

and it is for you to come trooping to me, if you are Christians.” The effect

and strength the Bishop’s words were such, and his language so severe, that

it acted like lightning. It frightened all and nobody dared to reply nor

even look him in the face. […]"

Bartolome de las Casas and the defense of Amerindian rights, by Lawrence A. Clayton and David M. Lantigua, University of Alabama Press, 2020

Another violent quarrel between the Spaniards and Bartolomé de Las Casas

"The aged Bishop was exhausted, having been on his feet all night long: he suffered from a lack of sleep and appetite, and the many speeches he had made had also weakened him. Entering his cell he could not expect to be served with a proper meal and he took just a mouthful of bread and a drop of wine. He had hardly swallowed this when rebellious citizens entered the convent and some particularly impudent men forced their way into his cell. When he saw himself surrounded by many swords and rapiers, so many shields and broadswords, he was upset and left so rapidly that he could not even swallow the crust of bread he had in his mouth, nor spit it out. He felt his last moment had arrived. So great was the noise and clamor that the friars, who sought to learn the cause of this hostile demonstration, could neither hear nor make themselves heard. […]

"This gentleman-landowner was followed by an honored resident who, taking

great liberties, oblivious of all courtesy, all semblance of respect, either

for the age or office of the Bishop, expressed himself in rudest terms. The

Bishop, listening patiently, then said: "I prefer not to answer you, sir,

and leave the punishment to God, whom you have outraged rather than myself."

(Fray Antonio de Remesal, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, Book 7, chapter 8, from Bartholomew de Las Casas; his life, apostolate, and writings by Francis Augustus MacNutt, Cleveland, U.S.A., The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1909)

Look at Las Casas' treatise on the slavery of the Indians (1552), in the page:

"Las Casas and Indian freedom"

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Saint Francis church

The point of view of the Conquistadores of San Cristobal:

"Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, bishop of Chiapas, has a passion that is as well-known as the passion of all the friars; they all know its root, but maybe they don’t and this passion could be a trick of Satan to obtain what he wants. Everywhere we hear their screams and their sound seems fair, but what Friar Bartolomé says in favour of the Indians is what we all want even more and achieve better than he could admit, by evangelizing them and treating them well. Satan seized the opportunity of their zeal to infiltrate himself and spread miserliness, jealousy and ambition to reach the goal that we all desire and that he alone professes on the public place. As he was full of what we said before, Satan managed to make him use wrong and false expedients to destroy God’s work and to lose your royal possessions. We are convinced that it will be so, if we examine what happened. This bishop does not understand, and the friars who are full of passion do not understand this either; Satan is blinding them and this is the ruse he uses and that we mentioned before. Your Majesty and Council seem to think that neither the priests nor the Bishop can stray from the right path since they pretend to unburden Your Royal Conscience, but Satan knows that he fools them to achieve his aim. We have seen and see in their behavior that they erred and keep erring every day, since they meddle in other people’s work, do not pay attention to their own work, and are obviously wrong. This sole fact should convince anyone with sound judgment of the above."

(Letter to the King of Several Conquistadores and First Colonizers, 20 March 1551, translated by Chantal Burns)

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, 2024, October, hundreds of women, adolescents and girls demand new Mexican government end violence and inequality in Chiapas

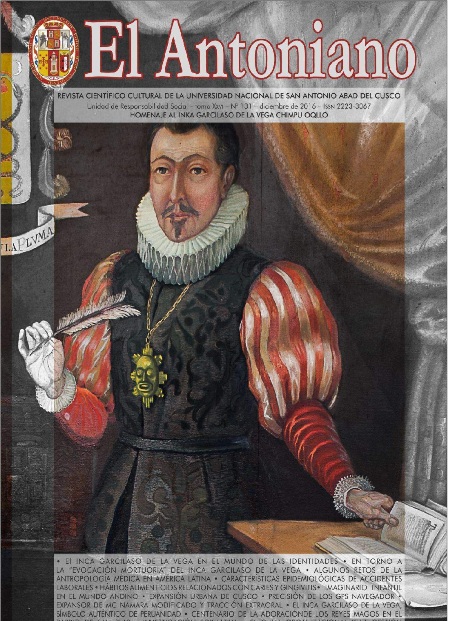

The opinion of Garcilaso de la Vega el Inca, son of a conquistador; hostile towards Bartolomé de Las Casas:

"Laws and ordinances established at the Court of Spain for the Government of both Empires of Mexico and Peru.

"Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, having arrived in New Spain in the year 1539, and having appeared in Madrid where the Court was held, started right away to claim, not only during his sermons, but also in his common discourses, that he was a great defender of the Indians and that he applied great zeal for their common good. But even though he said things that seemed themselves good and saintly, their tone was nevertheless full of a rudeness very difficult to pinpoint, which made these things difficult to implement. He proposed them before the Great Council of India and they were rejected […]. This did not stop him from persisting and he kept his objectives secret until the year 1542 when the Emperor Charles the Fifth returned to Spain from a very long trip through France, to the Netherlands and to Germany. This great Prince, who was very zealous, quickly accepted what the Friar proposed and told him that his conscience dictated to him to apply the new Laws and Ordinances that were for the common good of the Indians. Her Imperial Majesty, having heard this priest, ordered a meeting of his counselors and of prelates who had a great capacity and integrity at the same time. The proposal was made and a debate followed to such a level that the request of Friar Bartolomé took place. This was done against the feelings […] of these excellent men, whose long experience had made them capable of the most important negotiations regarding the Indies (and which) went against the new ordinances. Nevertheless, the Emperor signed them in Barcelona on 20 November 1542."

(Garcilaso de la Vega el Inca, Comentarios Reales, 1617, edición de 1722, Segunda parte, Libro tercero, capítulo XX.)

"These people became more and more imprudent, and told a thousand tales against those who had advised to establish the new ordinances. They were particularly angry at Friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whom Diego Fernandez adds to the list of those old conquerors of the Indies, as they knew he was the one who had planned and requested the creation of these laws.

"Diego Fernandez said that the Emperor made him Bishop of Chiapas, located in Mexico, but that he never dared take possession of this bishopric, because of the great disorder he was responsible for in the Indies. I remember that in the year 1562, I met him in Madrid and he gave me his hands to kiss after hearing that I was born in the Indies, but he did not talk much to me when he learnt that I was from Peru and not from Mexico."

(Garcilaso de la Vega el Inca, Comentarios Reales, 1617, edición de 1722, Segunda parte, Libro cuarto, capítulo III, Nuevas leyes y ordenanzas que en la corte de España se hicieron para los dos imperios de Méjico y Perú, translated by Chantal Burns)

Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca, on the cover of a review in Cusco, Peru (2016)

Aware of the imminence of his death, Bartolomé de Las Casas writes two epistles in 1565, short and sharp, restating the principles that had guided all his endeavors. One of the letters is to the Royal Council of Indies:

“First, all the wars usually called conquests were and are unjust and tyrannical.

Second, we have illegally usurped all the kingdoms of the Indies.

Third, all encomiendas or repartimientos are iniquitous and tyrannical.

Fourth, those who posses them and those who distribute them are in mortal sin.

Fifth, the king has no more right to justify the conquests and encomiendas than the Ottoman Turk to make war against Christians.

Sixth, all fortunes made in the Indies are to be considered as stolen.

Seventh, if the guilty of complicity in the conquests or encomiendas or repartimientos do not make restitution, they will not be saved.

Eighth, the Indian nations have the right, which will be theirs till the Day of Judgment, to make just war against us and erase us from the face of the earth.”

(Bartolomé de Las Casas, Memorial al Consejo de Indias, 1565)

Badajoz, Spain, the statue of Pedro de Alvarado, conqueror of Guatemala, smattered in red paint with the inscription: "Desangramiento de América", "He covered America with blood" (2020, October)

A critical view, by Friar Motolinia:

"I am amazed that your majesty and those of your councils have been able to bear for so long with a man so vexatious, unquiet, importunate, argumentative and litigious, in a friar’s habit, so restless, so poorly bred, insulting, prejudicial and troublemaking. […]

"When he came as a bishop and arrived in Chiapas, seat of his diocese, the citizens received him, as being sent by your majesty, with much love and all humility; they took him to his church under a canopy of honor, and lent him money to pay the debts he brought from Spain. Then within a very few days he excommunicated them, imposed fifteen or sixteen laws and conditions for confessions, and left them and went his way. Referring to this, Betanzos wrote him that the sheep had turned into goats and that he was such a good carter he had put the cart before the oxen. […]

"One of the things in this whole land that arouses the most compassion is the city of Chiapas and its province, which since Las Casas went there as bishop, has been destroyed in ehe temporal and the spiritual, he so inflamed everything. Please God that it not be said of him that he left his souls in the hands of the wolves and fled. […]"

(Fray Toribio de Motolinia, in Tlaxcala, to the emperor, from Tlaxcala, 2nd of January, 1555, in James Lockhart and Enrique Otte, Letters and people of the Spanish Indies, Cambridge University Press, 1976)

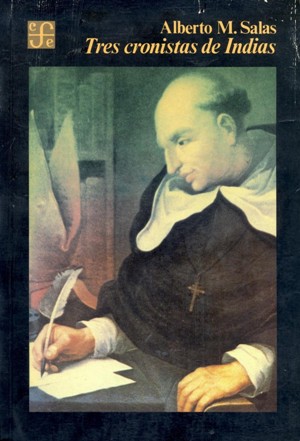

Friar Toribio de Benavente Motolinía in a Spanish stamp made for the 5th century of the discovery of America, 1991

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

Bartolomé de las Casas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Chiapas, San Cristóbal de las Casas. "Ningún hombre es esclavo, todos los hombres son iguales y susceptibles de perfectibilidad".

Licenciado Alonso López de Cerrato, President of the Audiencia de los Confines en Santiago de Guatemala,1548-1554:

« There was no doctrine among the Indians, nor friar or religious who dared to preach it or enter into the villages to do so, because they [the encomenderos] said that it was not necessary for the Indians to know any other “doctrine” except to serve their masters and to pay them their tributes. And in all the ways they could they prevented the Indians from knowing that there was justice or anything else except to serve and pay tribute to their encomenderos. And if some friars or religious went to preach to them [the Indians] or to indoctrinate them, they [the encomenderos] threw them from the village and did not consent. And it happened that while a friar was preaching to the Indians their encomendero (or one of his slaves) entered, and with slaps and blows took the Indians out of the church so that they might serve their master and not hear the doctrine. »

Residencia of Cerrato, Archivo General de Indias, Justicia 301.

The convent Santo Domingo in San Cristóbal de Las Casas (Ciudad Real), today

A stele in San Cristobal de Las Casas

The cathedral of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Here, in the former parish church, Bartolomé de Las Casas joined the inhabitants of the town.

Alberto Mario Salas, Tres cronistas de Indias, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1986. Bartolomé de Las Casas (Seville, 1474 - Madrid, 1566), Dominican, writing one of his works ("Historia de las Indias", "Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias", "Apologética Historia"...).