Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect, Fray Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

A FRANCISCAN TURNED ARCHITECT, FRIAR JUAN DE MÉRIDA

|

Convent of Mani, XVIth century frescoes behind the high altar

The convents in the Maya countries (16th century)

During the 16th century, the construction of monasteries directly paralleled the route of evangelization, in Yucatán, Chiapas and Guatemala. Franciscans and Dominicans broke up the native idols, pulled down Mayan temples, and built their own buildings, often using cut stones from Pre-Columbian structures, and destroyed pyramids as foundations.

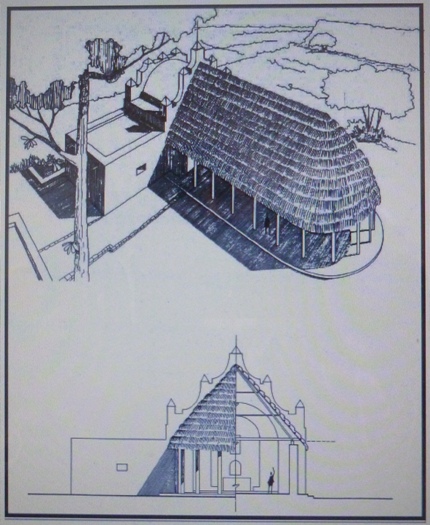

Prior to the completion of the convents, temporary pre-church and thatched roof huts were built to protect the outdoor placement of altars.

Then, the mendicant orders, with the help of native craftsmen and artists, erected hundreds of monastic complexes and parish churches across a wide space in Southeast Mexico.

Friar Juan de Mérida, a Franciscan turned architect

"The first religious name that comes to my mind, by order of seniority, is that of friar Juan de Mérida. He was one of the temporal conquistadores of this region, but he gave up what he earned from the conquest and was ordained as a lay friar in the convent of Mérida; and the first priests progressing quickly, we note from the list of participants to the first custodial Chapter that he was already professed monk and mentioned as residing in the convent of Izamal. He was an architect and this allowed God to give to the province a master capable of building temples in which His Divine Majesty could be worshipped and honoured by the new Christians who were being baptized. He built a great part of the buildings and the old church of the convent of Mérida, as well as the entire convent and church of Mani, that of Izamal, of St. Bernardino de Sizal in Valladolid, and parts of others; all of them solid and well-built constructions that attest to his competence and workmanship."

The Indians are the builders of the convent

"As it is hard to believe that he built so many convents, I wish to stress that a great number of Indians worked for him. It is said that he built the convent and the church of Mani in seven months, but that was thanks to the Cacique, lord of that territory, who provided six thousand Indians to help with the construction. This happy priest taught masonry and stone-carving to the Indians and organized the building site in such a way as to finish the work as quickly as possible. Since the Indians were many in this region and their heart full of divine grace, and the monks’ hearts were full of divine spirit, it seems that everything was done easily. Friar Juan did not, however, give up on his spiritual exercises in order to work on the site : he spent a great part of the night praying and the Lord supported him, giving him the necessary strength. He died in the convent of Mérida in the odour of sanctity and virtue."

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book 8, chapter 3, translated by Chantal Burns)

Virtual model of the convent of Maní. From the left to the right, the large open chapel (the biggest in the Yucatán) and the church façade. Behind, the cloister.

The architecture of the Franciscan convents in Yucatán

These convents may recall their European antecedents but represent a unique adaptation, by the religious who oversaw their building, to Indian habits.

The 16th century Mexican convent is usually a complex, consisting of a

large, walled atrium (atrio), a church and the convent itself. The church

was to have the traditional east-west orientation of sacred structures. The

atrium in front of the church was walled and three gateways defined

directional axes, the façade’s main portal of the church serving as the

fourth gate. At the intersection of the axes stood a tall cross.

The church has a single, concrete, barrel vaulted nave, with a choir loft

above the

West entrance.

A gilded wood retable rests beneath the

East end, behind the main altarpiece, and usually covers

entirely the wall of the vaulted apse. A side

door to the South leads outside to the atrium. The house of the monks and

the cloister were generally attached to the North wall of the church and a

porter's lodge (porteria) faced the atrium.

An open chapel (capilla abierta or capilla de Indios) abutted the church

façade on one side or the other. The construction of churches, rapid though

it was, failed to keep pace with the thousands of converts who filled the

existing buildings to overflowing. The monks erected small chapels, large

enough to shelter the altar and so constructed as to render it visible to

great numbers of Indians outside. As the years passed, many parish churches

arose until there were enough to serve the people. The open chapels were

gradually abandoned or enclosed and dedicated to special uses.

A thatched shelter, called ramada, was built in front of the open chapel

Description of a ramada by Antonio de Ciudad Real (Tizimín, Yucatán, 1588):

"In the grounds or patio of the convent of Titzimin (which is square and paved with mortar with a chapel in each corner, and with many orange and other trees laid out) is built a ramada of wood, covered with guano which are leaves of certain palm-trees, very large, wide and long, holding many people, and very curious in that in all of it, there is neither nail nor rope, and withal it is most strong; it has no walls, by reason of which it is entirely open and the air enters from all sides, but only forked poles, posts or columns of very strong wood upon which it is built, all tied with vines, which are (as has been said) like willow, very pliable. In that ramada the people gather to hear sermon and mass, which is said in a large chapel at the entrance of the same ramada. The Indians assist from the choir, which is at the side of the chapel, in which also there is usually the baptismal font and on other side is the sacristy. Thus it is in all the towns of the province where there is a convent as well as where there is none, for it is necessary because of the excessive heat there, although in some few towns the baptistery is in the same chapel and in others it is in a special room and place."

(Antonio de Ciudad Real, Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva España, Vol II, Chap CXLIII, Translated by Ernest Noyes, in Fray Alonso Ponce in Yucatán 1588, The Tulane University of Louisiana, New Orleans, 1932)

Another unique trait of 1,500s Mexican Christian architecture is the posa chapel. Relatively small edifices and open on two sides, these were placed at the corners of the atrium and usually used as processional passageways during mass.

Beside Fray Juan de Mérida, few records exist of professional architects working in southeast Mexico during this early period. Mostly the convents and churches were conceived by friars who held little if any formal architectural training. They oversaw the constructions but placed the actual labour in the hands of the local Indians.

Many of the early convents actually resemble medieval fortresses. These awe-inspiring fortresses certainly aided in dissuading attacks, although their battlements appear to have been largely decorative instead of defensive. The bare surfaces of massive walls were a necessary result of untrained labour and of amateur design.

The church façades of the 1,500s appear sober when compared to the ornately Baroque that was to come in the subsequent two centuries. The Latin crosses and the cupolas represent later additions to 16th century churches, and abound in 17th century Yucatán, Chiapas and Guatemala.

In their architecture, the Franciscans tended to adhere to a humble simplicity, intrinsic to the nature and teachings of their founder; the Dominicans were at times grander in their constructions.

A rough territorial division of labour existed, the Franciscans expanding throughout the Yucatán, while the Dominicans focused their efforts in Chiapas and Guatemala.

Devastation of the indigenous populations by plagues and secularization of the parishes by the Catholic Church brought the most intense period of monastic architectural construction to a close some years before the end of the 16th century.

Maní, 2024, March

The convent of San Miguel Arcángel in Maní

The monastery of Maní, Convento San Miguel Arcángel, work of Fray Juan de Mérida, was constructed towards 1549, with the help of about six thousaVillagend Indians of the Mayan dynasty of the Xiues.

Maní was the site of the famous "Auto de Fe" of 1562, when Bishop Fray Diego de Landa burned Mayan manuscripts and codices.

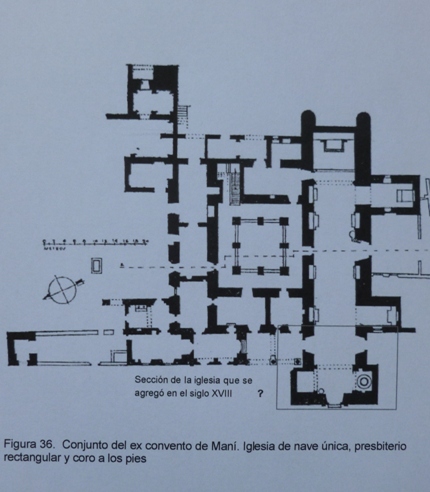

"The convent of Mani is the third oldest among those in the province since the first custodial capitular assembly of 1549. Its church has a vaulted nave and an additional one for the Indians, both dedicated to San Miguel Arcángel. From there, the church of the village of Zán is administered, as well as those of Saint Mary Magdalena of Tipikal and Saint Peter Apostle of Chapab. The first Fathers created a hospital in Mani, with the hope of obtaining an annuity and care for the poor Indians, but to no avail. The building still stands (in 1688) and its chapel is used by the brotherhoods of the Virgin of the place and the village of Tipikal. Other hospitals have been built, and were later abandoned for the same reason and I will not talk about them here."

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book 4, chapter 20)

Map of the convent of Maní. The part of the church in the square was built in the 18th century. (From: Marisol Ordaz Tamayo, Arquitectura religiosa virreinal de Yucatán, Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2004)

The Father Commissary Fray Alonso Ponce visits the convent of Maní (1588)

"Thursday, September 22nd, the Father Commissary left at two o’clock in the morning, by the road from Oxkutzcab, and travelling the three leagues by the same road which he had taken on going, arrived before day at the said town, where he found at that hour all the people assembled, and they were waiting for him with dances and many ramadas and music. They made for him even a greater fiesta than before and he entered the convent where he waited till dawn and then continue his journey, and travelling two leagues of fair road arrived early at the town and convent of Maní. At the end of the first league there was a large ramada with provisions, in which were many important Indians, set up to attend any of the friars who might need breakfast; all along during the other league he met Indians from Maní and other towns of the guardianía, afoot and on horseback, who came out to see and receive him and with these the corregidor of that province came out. From the entrance of the town to the gate of the convent patio there were many ramadas and on top of each one of four or five of them was a chapel of Indians choristers, singing motets in canto de organo; the others had a very comic puppet-show, and on the last were many crosses, andas and banners, and in all of them a great multitude of Indian men and women. Afterwards the chief Indians came with presents of many turkeys, melons, pitahayas [dragon fruits], iguanas, candles and sticks of white wax, honey and bananas and other fruits.

"The town of Mani is the largest of that province; it had more than three thousand tribute-payers (tributarios), and there are in it many gentlemanly people (gente ahidalgada) and in breeding and intelligence it seems to excel the others. They of Mani have been and are very devoted to our state, very gentle and obedient to our friars; these people of Mani were the first who sent to offer peace to the Spaniards, and who received them in peace when they entered Yucatan. [...]

Maní, Magic Village, 2023

"The convent of Mani (dedicated to San Miguel) is finished, with its upper and lower cloister, dormitories, cells and church; all is of stone and mortar, and the church vaulted, with its chapel of the same, and lattice-work (algunos lazos de cantería): it has a good garden, in which are many orange, banana, guava, alligator-pear, plum and some coconut-trees, and it is irrigated with the water drawn by another anoria in the same garden. The Indians have a very large and handsome ramada, more than two hundred feet in length and more than eighty feet in width; in this they have, against the convent, their chapel, made of stone and mortar and vaulted, with bonded stones, and this they call San Francisco. For many year two birds called guenqueqbac (ah-cencenbac) in that language, and sometimes only one, have been lighting on this ramada just before nightfall and wait for the bats, of which there are many in that country, to come out and one seeing one of them they fly down and dart and seize it without fail; these birds greatly resemble falcons. That ramada is within a square patio, in which there are many orange-trees in rows, and four chapels, one in each corner. In this patio, next to the church, is the school for the Indians, the best in the whole province, from which more and better singers come, because they have funds for the masters and fiscales, and thus great care is taken in all things. A lay brother, called Fray Juan de Herrera, very able and good bearing, put this school in order in times gone by, and taught many Nauatlatos our Castilian language and who, desiring to die a martyr, afterwards went to Mexico and from there to the Chichimecas where those barbaric infidels killed him. For the service of this school, there is another anoria in it, from where water is conducted in canes (encañada) to a stone trough in the patio of the church, in order that the people may drink at Easter-time and other solemn feasts when there is a concourse of Indians. Four monks were living in that convent; the Father Commissary visited them and remained with them four days. All the Indians of that province are Mayas."

(Antonio de Ciudad Real, Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva España, Vol II, Cap CLIV, Translated by Ernest Noyes, in Fray Alonso Ponce in Yucatán 1588, The Tulane University of Louisiana, New Orleans, 1932)

You can find the relation of Fray Alonso Ponce's trip through the convent route of Yucatán, in the page "The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century"

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The cloister of the convent of Maní. Thick and heavy walls distinguish the convent architecture, like as in Maya buildings.

The convent of Mani, three centuries later:

"Toward evening we strolled over to the church and convent [of Mani], which are among the grandest of these early structures erected in Yucatan, proud monuments of the zeal and labour of the Franciscan friars. They were built under the direction of Friar Juan of Merida, distinguished as a warrior and conqueror, but who threw aside the sword and put on the habit of a monk. According to Cogolludo, they were both finished in the short space of seven months, the cacique who had been lord of that country furnishing six thousand Indians. Built upon the ruins of another race, they are now themselves tottering and going to decay.

"The convent had two stories, with a great corridor all round ; but the doors were broken and the windows wide open, rain beat into the rooms, and grass grew on the floor.

"The roof of the church formed a grand promenade, commanding an almost boundless view of the great region of country of which it was once the chief place and centre. Far as the eye could reach was visible the great sierra, running from east to west, a dark line along the plain. All the rest was plain, dotted only by small clearings for villages.

"My guide pointed out and named Tekax, Akil, Oxcutzcab, Schochnoche, Pustonich, Ticul, Jan, Chapap, Mama, Tipika, Teab, the same villages laid down in the ancient map, whose caciques came up, three hundred years before, to settle the boundaries of their lands ; and he told me that, under a clearer atmosphere, more were visible."

(Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, Vol 2, by John Lloyd Stephens, Frederick Catherwood, illustrator, 1843)

R. Flores Guerrero, Las capillas posas de México, Enciclopedía mexicana de Arte, México D. F., 1954

The convent of Mani in the times of Caste War

"We found a building two stories high, containing 14 rooms in a state of ruin, surrounded by grounds which had at one period, been highly cultivated if we may judge by the many conveniences which we encountered for the purpose of irrigating, and the pretty accomodation of flowerbeds and vases. The only person who put in an appearance was an old indian woman. We asked for something, but could not even obtain tortillas. The place was so picturesque that we loitered half an hour to examine it. Many small huts formed a village. These were occupied by the servants of the farm, who, in this case, pass the greater part of the time doing nothing. This state of ruin is partly owing to the indolence of the people and partly to the indian war. When they invade, they burn, destroy, rob what they can carry, and clear out leaving desolation behind them. The people make no attempt to put things right again."

(Alice Dixon Le Plongeon' diary, 19 may 1875, published with title "Here and there in Yucatan")

Mani, the convent circa 1930, still half ruined. The open chapel was closed by a wall and re-employed.

El incendio de Maní (abril 1848) durante la Guerra de Castas

"La fuerza de Cecilio Chí que había salido de Tinum con destino á nuestras fronteras, cayó repentinamente sobre el pueblo de Maní, cuyos habitantes vivían desprevenidos, por la confianza que tenían en los convenios de Tzucacab, y con cuyo motivo los invasores no encontraron ninguna clase de resistencia. Pudieron cebarse, pues, en aquella poblacion indefensa, y además de haberla reducido á cenizas, asesinaron á mas de doscientas personas en sus casas, en las calles y en el mismo templo. Un sacerdote que pudo escapar casi desnudo de aquella horrible matanza, fué el primero que llevó á Oxkutzcab la triste noticia, en los momentos que comenzaban á hacerla sospechar las columnas de humo que levantaba el incendio. […]

Rotos de hecho los tratados de Tzucacab con los dos sucesos que acabamos de referir, Jacinto Pat comenzó á hacer sus preparativos para emprender la campaña con nuevo vigor. Don Miguel Barbachano se regresó á Mérida y el general Llergo comenzó á dictar medidas para evitar otra sorpresa como la de Maní."

(Eligio Ancona, Historia de Yucatán desde la época más remota hasta nuestros dias, Parte cuarta, La guerra social, Capítulo VII, Mérida, 1880.)

Portada del libro de Severo del Castillo, Cecilio Chi, Editorial Club del Libro, 1949

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

The convent of Maní, in the Yucatán, built by Fray Juan de Mérida. To the left, the large open chapel. In the foreground, the church façade. The façade belongs to the 18th century and its style is considered as sober baroque. The main access has a half point arch with an unadorned moulding. A stone statue of the Archangel Saint Michael complements this austere façade.

Convent of Maní. The open chapel. This open chapel calls the attention due its size that competes with the size of the temple. It is a simple vault that has flute as the only decoration in all the arch and the jambs.

Maní Convent. Saint Michael

The church of Maní, 2023