Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

IN THE YUCATÁN, A CHURCH IN EVERY VILLAGE

|

Uman, Yucatan

The Franciscans built hundred of churches in the Yucatán

Transversing the Yucatán peninsula, especially the lesser highways north or south of the motorway between Mérida and Valladolid, one passes through dozens of local churches originally built in the sixteenth century. Many of these structures preserve the original sixteenth-century components.

The amount of work that the Franciscans did was truly prodigious. By the end of the sixteenth century, only seventy years after the Conquest, there were three hundred churches and monasteries, built by the brothers (and above all by the Maya Indians), scattered throughout the Yucatán.

By the end of the century, churches had been built on nearly every former holy site in northwestern Yucatán, forming a network in which no guardiania or visita was more than a day’s walk apart in any radial direction.

All of this came from a strong political will, expressed in numerous texts among which is the following dating back to the period when the Yucatán was under the rule of the Audiencia de Guatemala (Antigua Guatemala):

They demand that the Indians learn how to build churches

“At the same time, I request and order that all the villages of these provinces and their inhabitants build in the villages good churches in adobe and stones, with elaborate details as required by divine worship, and I request that this should be done in the next two years, and that everyone should work on building the churches and that no one should be exempt from it. And I also request that there should be no more than one church per village for the use of the villagers, for this is good for the peace and ease of the inhabitants. And no cacique, no nobleman no other person should feel free to erect or build a church, a chapel or a hermitage. If this was ever done, the building should be demolished and if anyone dared to do so, he should be whipped one hundred times. And there should be no more than one principal church where all should gather, and I request that these churches should be well adorned and decorated, always clean and locked so that no animal enter them, and that all have doors and keys, and that no one should dare sleep inside them or store anything in them, or else etc.” In the name of the King, Tomás López, Representative of the Audience of Guatemala, 1552.

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book 4, chapter 17)

The friars developed an organizational form to facilitate their task, the doctrina. The doctrina was a center or school of religious instruction located in the convents of Franciscan order. The missionaries also extended their ministry to pueblos sujetos in which they induced the Indians to construct churches. The larger villages might be provided with a resident priest, but most were pueblos de visita, so called because one of the fathers visited them periodically to catechize, preach, and say mass.

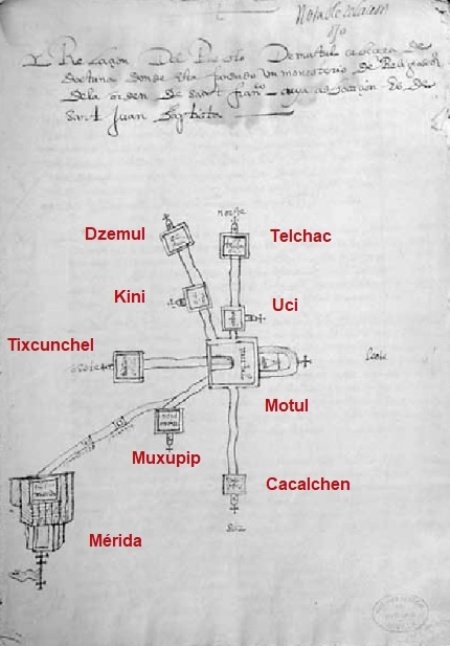

The map of Motul in the Relaciones histórico geográficas de la Gobernación de Yucatán, 1581)

"The image was drawn by either Juan Pech or Juan Cumci de Landa, both Maya scribes working for Martin de Palomar. In the map, Motul is situated at the center. Its affiliate towns are connected by five roads (or in Mayan, sacbeob, singular sacbe): one to the south, one to the north, one to the northwest, one to the west, and one to the southwest, which ends at Tihó-Mérida. The map is oriented to the east, rather then the north as generally favored by Europeans and as stipulated by royal instructions. This compositional arrangement is intriguing; despite being produced for Spanish administrative purposes, the map exhibits Maya spatial orientation. Indeed, all the extant provincial maps produced in Yucatán, including the Motul map, are oriented to the east. It seems that the Maya had a proclivity to the eastern orientation.

"However, the Motul map also confirms the omnipresence of Spanish cultural authority, as its imagery assits in fixating Mérida as a new center of power. The map conveys Spanish preeminence in several ways. First, the positional value of Motul to Mérida was a requirement of the royal instructions that informants had to fill. Instructions 11 and 12 explicitly asked scribes to indicate the distances among colonial capitals and their towns; in this instance, it specifies « Motul was seven leagues northeast of Mérida ». The communities were required to officially recognize their positional location to provincial capitals, thereby making informants aware of the allegiance to larger political and cultural networks. Second, each of the nine towns referenced on the Motul map are identified by square, bell-towered church façades, below the bell tower of each building is the name of the community."

C. Cody Barteet, Architectural Rhetoric and the Iconography of Authority in Colonial Mexico, The Casa de Montejo, Routledge, New York, 2019

Diego López de Cogolludo describes this organization and gives a precise and long list of the religious districts in the Yucatán (in the XVIIth century, after the reorganization of 1602):

Thirty-five Franciscan convents in the Yucatán

“Administering the holy sacraments and evangelical preaching to the Indians of this bishopric and Government of the Yucatán are spread out between the clerics and us, the priests of our Father Saint Francis, who belong to the province of San Jose, and where there was never any interventions by priests of a different order. The clergy has twenty-two missions and parish vicarages which are distributed according to the list established under the tutelage of royal patronage in a public adjudication. We priests have thirty-five convents, which tend to the Indians, and have guardians elected in the provincial chapters, and the preaching ministers are nominated and introduced according to the procedure established by royal authority so as to follow the royal patronage: the guardians are at times also ministers, and sometimes, other priests discharge this function, according to how well they speak the language of the Indians. There are also two other missions, in which the heads of the convents do not have the title of guardian, but that of vicar, although they are elected by the chapters, and the Dominican Fathers administer a vicarious in Tabasco. Let us now turn to the list of missions and their annexed villages or visits, which possess baptismal facilities and patron-saints; they are the following.” […]

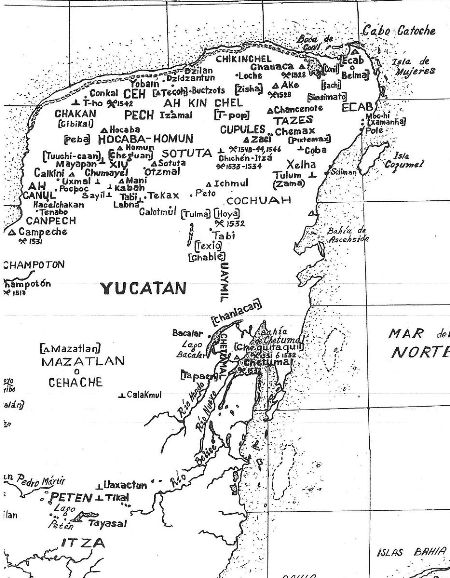

Towns of Yucatán, in Robert S. Chamberlain, Conquista y colonización de Yucatán, 1517-1550, Editorial Porrúa, México, 1982

Hocabá

“The parish of Hocabá was also one of our convents until the year 1602, with Father friar. Francisco de Piña as its last guardian. The church of Hocabá is dedicated to our Father Saint Francis; those of its villages to the Ascension of Our Lady (Tzanlahcat, of which the other villages of Huji and Tixcamahil depend), to San Juan Evangelista (Zabcabá), and San Pedro Apostol (Huji ).” […].

Yaxcabá

“The parish of Yaxcabá, administered by the convent of Zotuta, has its headquarters in Yaxcabá proper, whose patron saint is our Father San Francisco. Its villages are Mopila (dependent on Saint Mathew Apostle), Tixcacal (Saint John the Baptist) and Tacchebilchen (Exaltation of the Sacred Cross).” […]

Peto

“The parish of Petu (Peto) is itself devoted to the Assumption of Our Lady; the dependent villages are Tahdziu, dedicated to our Father Saint Bernard, Tixalatún (our Father San Francisco), Tzucácab (Saint Mary Magdalena) et Calotmul (Saint Peter Apostle).”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book4, chapter 19)

Tecoh

“The convent of Tikoh, whose church is dedicated to the Assumption of Our Lady, was built and baptized convent in 1609. It is responsible for mass in the churches of the Magi in the village of Timucuy and Saint Gregory Pope of Telchaquillo, as well as in the churches of the Nativity of Our Lady of Acanceh, of Xiol and of Chaltun that belong to the same concession.” […]

Muna

“The administration of Muna has been managed by a convent since the year 1609; the patron saint of its church is Saint John Evangelist. The visits of Saint Anthony of Padua in the village of Zaclum and of Saint John the Baptist of the Indians of Abalá and Becyá are its dependents and they all belong to the same concession.” […]

The Conkal convent during the “corte de ceiba” festival (cutting the ceiba tree) in September 2024

Conkal

“The convent of Cumkal comes in fourth place in the first custodial chapter of 1549. Our Father Saint Francis is patron of its church. Its visits are Saint James of the village of Chicxulub (Chhic Xulub), Saint Ursula of Chablé (Chable), Saint Peter Apostle of Chulul, and Saint John the Baptist of Zicipach (Zicil Pach). […]

Uayma

“The convent situated today in the village of Uayma (it was transferred from the village of Tinum where it was first built in 1681) dedicated its church to our Father Saint Dominique; its visits are the Immaculate Conception of our Lady of the village of Tinum, the Assumption of Kauva and Saint John the Baptist of Cuncunul.” […]

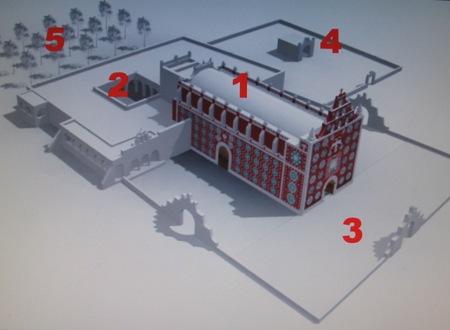

The monastery of Uayma (virtual model): 1. the church, 2. the cloister, 3. the atrio, 4. the cemetery, 5. the orchard

The temple and convent of Uayma were used for evangelization by the Franciscans. The encomendero Juan Vellido tells in his report that the church was made with stones from Mayan mounds found in the town: «Ay en este pueblo de Guayma unos cues de piedra hechos a mano, muy altos, de los quales se sacaba piedra para hazer la yglesia y aposentos délos Religiosos» [Juan Vellido, alcalde ordinario, Relación de Uayma, Relaciones histórico-geográficas de Yucatán,1579].

Friar Diego de Cogolludo in his History of Yucatan says that the church was a great place of devotion: «Y no sólo los españoles e indios de la jurisdicción de Valladolid, de donde dista dos leguas, sino el resto de esta tierra, tienen gran devoción con ella [la Candelaria de Uayma], y hay en su iglesia muchas insignias de beneficios por su invocación recibidos.»

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucatán, 1688)

Dzidzantún, convent of St Clara of Assisi

299 main churches

Thus, in this bishopric of the Yucatán, there must have been 299 churches dedicated to the glory of God our Master and honoring its saints […]. Our priests of the province built 212 of them, excluding the churches of the village administered by the convents (visits), that I was unable to count. Of this total, we have 151 churches proper, of which 145 parochial churches with baptismal facilities. Moreover, we administer 38 convents, 25 of which we built ourselves.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book 4, chapter 20, translated by Chantal Burns)

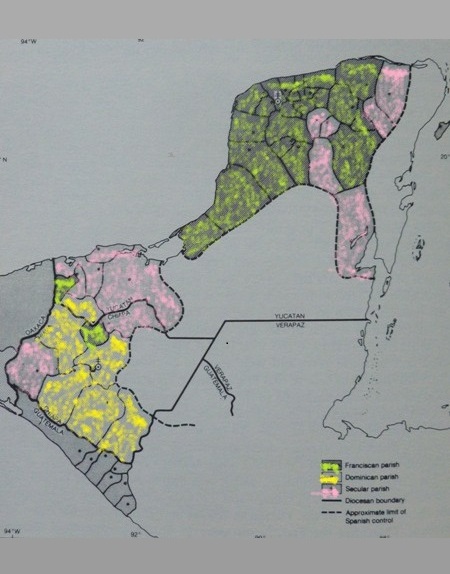

Parochial Division in 1590: green, the Franciscan parishes, in Yucatán; pink, the secular parishes; yellow, the Dominican parishes, in Chiapas; the dotted line delimits the countries supervised by the Spaniards (after Peter Gerhard, The Southeast Frontier of New Spain, Princeton University Press, 1979)

Friar Julián de Quartas, Franciscan architect and craftsman :

"Father Friar Julián de Quartas came with the priests whom the Saint Bishop Landa brought along in our Province. He was born in Almagro and became a priest in the province of Castilla. And we can say that he was one of the religious men the most useful for the good of the Indians, among all religious men present there, because he was extremely kind with the Indigenous people and knew their language so perfectly that no one could speak it better than him. He taught many of us the Mayan grammar and knew how to sum up its many complex rules into some simple ones. He liked the Indians very much and taught them the crafts of painting, gold leaf, sculpture and all other kinds of crafts; he excelled in that field and when this religious saint did not know a particular technique, he learnt it to teach it later to the Indians. And thanks to him, a great many of them are now painters, gold leaf painters, sculptors etc…, and they refined their skills with the Spanish Masters now living in the county to such an extent that they can be compared to the best craftsmen in the world. But this kind priest, when he began training them, is responsible for their calling. His pupils have filled churches with superbly sculpted altarpieces, beautiful paintings and other ornaments. In addition to this occupation, he was a confirmed architect and built two convents and their churches with their great chapels, which are the most beautiful in our Province, at least among those built recently. And not only did he supervised these constructions, but everywhere he went he built sundials, all different and trained other people, including Indians, to build more of them. There would be much more to say about his actions, which were so beneficial to our Province and to the indigenous people. He left Spain when he was nineteen and worked in the Yucatán for thirty-eight years. He died when he was fifty-eight; he deserved to be praised for his faith and his work."

(Bernardo de Lizana, Historía of the Yucatán, devocionario de Nuestra Señora de Izamal y conquista spiritual, 1633, part II, chapter XV, translated by Chantal Burns)

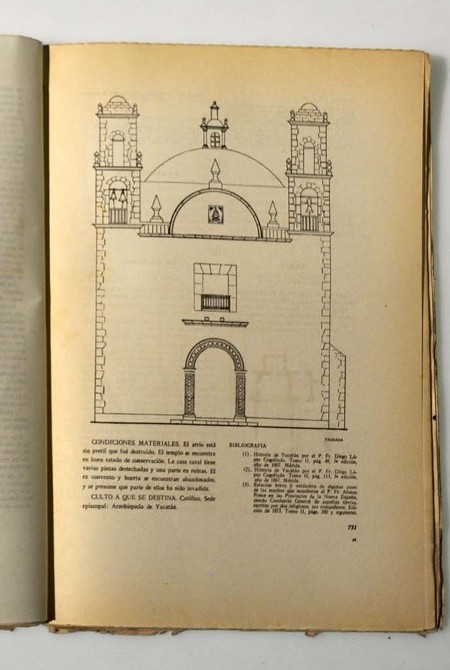

Tixkokob church (Catálogo de construcciones religiosas del estado de Yucatán, Recopilación de Justino Fernández, Talleres gráficos de la nación, México, 1945)

Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar, letter to the Council of the Indies, 1556

:

«The excessive costs and expenditures and personal services and the sumptuous and superfluous works which the religious are erecting in the Indian villages at the Indians’ expense, should be remedied. With respect to the monasteries, in some places they are so grandiose that, although they are designed to accommodate no more than two or three friars, they would more than suffice for Valladolid. When a house is completed and another friar moves it and takes a notion to demolish it and remove it elsewhere, he does so. It is nothing for a religious to begin a new work costing ten or twelve thousand ducas […] and bring Indians to work on it in gangs of five hundred, six hundred, or a thousand, from a distance of four, six, or twelve leagues, without paying them any wages, or even giving them a crust of bread. […]

The personal service of the Indians in the monasteries is very excessive: gardeners, doorkeepers, cleaners, cooks, sacristans, messengers, all without a cent of wages. There is a very large number of cantors in the service of the Church; in one monastery we found a hundred and twenty Indians serving as cantors, without counting the sacristans and acolytes and players [of musical instruments] […] and, since the cost of such works and the rich and superfluous ornaments is met by assessing these poor people, the caciques and head men, who are suppose to take out a hundred ducas from the community strongbox, take out a thousand for themselves. No one knows this better than the friars, who have told me that the caciques and head men wish the friars to ask them for money, so that they may with this pretext make an assesment for themselves.»

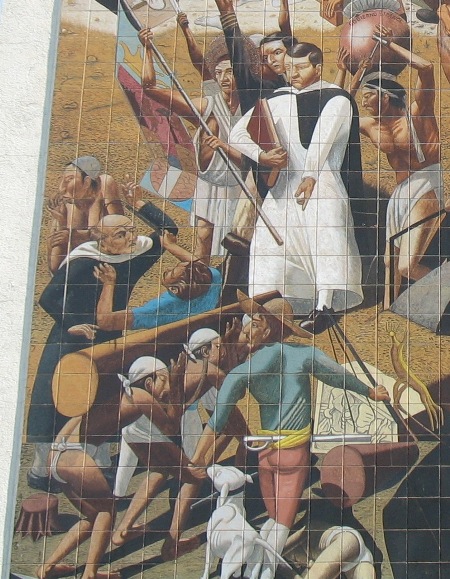

The Indians built the churches -in Chiapas, Dominican land- (fresco by César Corzo, 1994, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Tuxtla Gutierrez)

Alonso de Zorita (ca. 1511-1585), Brief and Summary Relation of the Lords of New Spain, completed in 1585

:

"In the old days [the Indians] performed their communal labor in their own towns. Their labor was lighter, and they were well treated. They did not have to leave their homes and families, and they ate food they were accustomed to eat and at the usual hours. They did their work together and with much merriment, for they are people who do little work alone, but together they accomplish something.... The building of the temples and houses of the lords [principales] and public was always a common undertaking, and many people worked together with much merriment. They left their houses after the morning chill had passed, and after they had eaten what sufficed them, according to their habits and means. Each worked a little and did what he could, and no one hurried or mistreated him for it. They stopped work early, before the chill of the afternoon, both winter and summer, for they all went about naked or with so few clothes it was like wearing none. At the slightest rainfall they took cover, because they tremble with cold when the first drops fall. Thus they went about their work, cheerfully and harmoniously. They returned to their houses, which, being very small, were cozy and took the place of clothing. Their wives had a fire ready and laid out food; and they took pleasure in the company of their wives and children. There was never any question of payment for this communal labor. In this same way, with much rejoicing and merriment and without undue exertion, they built the churches and monasteries of their towns. These are not as sumptuous as some have said, but accord with what is necessary and proper, with moderation in everything…

"Neither drunkenness nor their well-organized communal labor is killing [the Indians] off. The cause is their labor on Spanish public works and their personal service to the Spaniards, which they fulfill in a manner contrary to their own ways and tempo of work. To make this clear, I shall relate some things that have been and are being done to the Indians... What has destroyed and continues to destroy the Indians is their forced labor in the construction of large stone masonry buildings in the Spaniards' towns. For this they are forced to leave their native climates, to come from tierra fria to tierra caliente, and vice versa, 20, 30, 40, and more leagues away. Their whole tempo of life, the time and mode of work, of eating and sleeping, are disrupted. They are forced to work many days and weeks, from dawn until after dusk, without any rest."

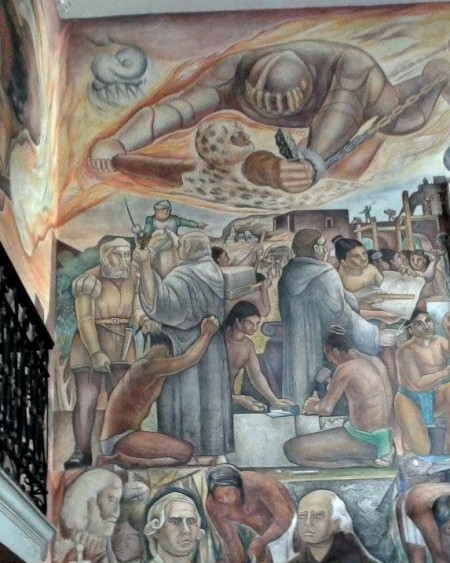

Friars controlling a building site, Colima, Government Palace, mural by Jorge Chávez Carrillo, 1954

Gerónimo de Mendieta:

"The acquaintance with Spanish techniques also led to a perfection of skills the natives had cultivated before the conquest. Stonemasons and sculptors had worked without iron producing masterpieces, but now, in control of pickaxes, stonecutter hammers and other iron implements and acquainted with the works created by Spanish artits, they made enormous advances. They now produced proper arches of all types, portals and windows, sculptured masks, and they built many fine churches and residences for the Spaniards.

"What they have not learnt was to make vaults. When the first one was built by a Spanish craftsman and stonemason for the chapel of the old church of San Francisco in Mexico, many of the Indians were amazed when they saw the vault and simply could not imagine how it possibly stayed in place without scaffolding. They did not venture to walk beneath the vault, but they lost their fear when they realized how firm the ceiling was. Shortly afterwards the Indians constructed the vaults of two small chapels which still form part of the cathedral of Tlaxcala. Since then they have built the roofs of numerous fine churches, also in the tropical parts.

"Their carpenters used to cover the palaces of their kings whith fine wood, they also produced much else, but today their work has changed, for they have acquired proper carpentry and joinery, as well as workshop practices, enabling them to produce anything Spanish tradesmen create, as well as works of masonry and architecture."

Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta, Historia Eclesiástica Indiana, Book IV, Chapter 13, 1595

Indians building a church (mural by Pedro Cruz Castillo -1912-2004-, Santuario de la Guadalupe, Acámbaro)

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

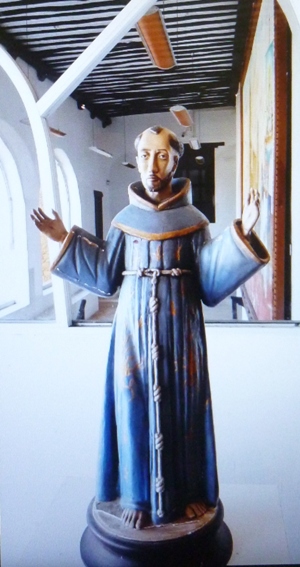

A Franciscan friar, in the Museo de Arte Sacro located in the convent of Conkal

Hocabá

Yaxcabá, May, 2021, a political demonstration in front of the church. This triple-towered church was finished in 1753.

Peto

Tecoh

Muna