Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matias de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

A DOMINICAN NURSE, MATÍAS DE PAZ

|

Fray Matías de Paz

In Guatemala and New Spain, the missionaries further strove to relieve the physical miseries of the Indians, a task made particularly urgent by the ravage of epidemics. The Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians built hospitals with the labor, money, and alms of their charges, who also provided the nursing staff. These establishments had ameliorative as well as medical functions. They were places where the poor and infirm might find care and sustenance; they were free provisioning depots where, in time of need, the Indians could obtain food and clothing.

By the middle of the 16th century, the compassionate Dominican Brother Matías de Paz didn’t take long to notice the indigenous poor dying on the streets of Antigua Guatemala due to cold, bad food and lack of hygiene as they worked digging foundations for noble housing. He bought a site near the plaza of the church of Candelaria, off the northeast end of Antigua, and built a thatch roof house to shelter the sick he “carried on his shoulders when they could not walk.” He went through the streets collecting funds to feed those in what would become Hospital de los Indios, or Hospital de San Alejo, the second to be founded in Guatemala.

With increasing numbers in his care, Matías de Paz realized he needed help and moved the work to across the street north of the Santo Domingo monastery. Even then, support became so difficult that a man and his wife were named to go to the butchers and solicit a pound of meat for each patient.

Hospital San Carlos, Altamirano, Chiapas

The hospital was founded in 1969 by the Dominican Mission

The Indians are exploited and mistreated by the Spanish settlers

“The strong pressure exerted by the Spaniards did not leave them (the Indians) the choice to do their work in their usual way, particularly in Santiago de los Caballeros (Antigua Guatemala), on the buildings to be built on the new location of the town, which was chosen in 1541: every inhabitant wanted to work faster than the other in order to finish his house, and such a competition was to the disadvantage of the poor Indians who were mistreated, and since they did not have enough food, they got sick and many of them died with their back against the walls, or in the ditches they dug to extract soil used to build the adobe walls. The Fathers of Saint Dominique, whose hearts were full of kindness and love of God, could not bear it and were distraught by so much misery endured by their brothers; Father Pedro de Angulo in particular, and especially Father friar Matias de Paz who, more than any other Father, lived most of the time in the convent. Both undertook to remedy the situation. Father friar Matias de Paz gathered some alms and bought a piece of land near the convent, where stands today the hermitage of Our Lady de la Candelaria, alongside the market or Saint Dominique square, today called the Count square.”

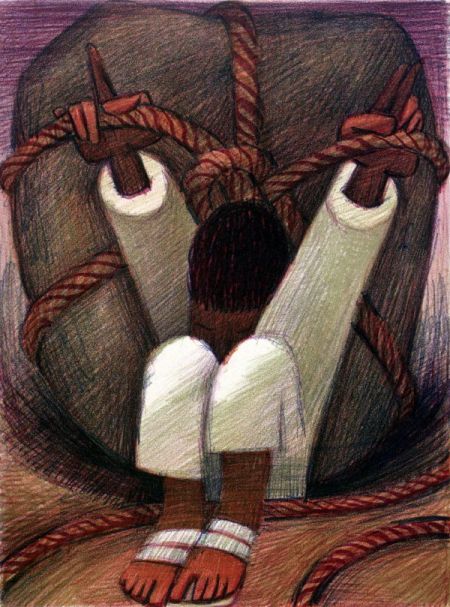

Jean Charlot, cargador, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1933

The Dominicans build the hospital of the Indians of Antigua Guatemala

“Father friar Matias de Paz finds a piece of land on which he built a house covered with straw, to the limits of his capacity, and he took in the sick Indians he met in the streets, with such love that he did not hesitate to put them on his shoulders when they were incapable of walking.”

“This hospital of the Indians got its food from the convent of Saint Dominique, where meals were cooked. And since the Fathers thought that they were too far away to bring them the food on time, and since they could not visit them very often, they bought with the money of the community another piece of land adjacent to the convent, only separated from it by a street, as their kindness instructed them to do. Father Blas de Santa Maria, a priest of great virtue and compassion for the poor, helped Father Matias de Paz a lot in this transformation of the hospital. Those coming to the new hospital were so many that they did not fit in the rooms, even if the beds were squeeze, and the convent did not have the financial resources to tend to them adequately. The Fathers decided to call on the generosity of the very Christian king of Spain (Philip II) and to inform him of their actions, and requested a permanent alms for the new hospital. His Majesty considered this request as a person who felt in his soul the misery of the poor Indians and thanked the Fathers for treating them with such kindness. He wrote to the Audience of Madrid, on 18 May 1553, through his secretary Francisco de Ledesma, and asked about the feasibility of building a hospital for the Indians and about its cost and tax amount.”

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, Historía de la provincial de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 9, chapter 21)

Matias de Paz built the hospital without neglecting to pray

“Father friar Matias de Paz could have been the praise of the most famous city in Spain whose son he was, and whose parents of most noble lineage gave birth to him. Little was said about this man concerning the year 1538 when he became priest, and concerning the San Alejo hospital. I have yet to describe the daily ordinary habits that were his. […] What was marvelous about this priest was that he spent his days making raw bricks (adobe), laying them down while covered with mud and dirt, telling the Indians what to do to build the house; and while he was busy doing that, he was sometimes called to say mass: he then dropped the ruler or the trowel or the pickaxe he often used to dig the soil, he cleaned himself up, went to the sacristy, washed up and went on to say a sublime mass, cried a lot and was deep in thought as if he had been praying for a long time, meditating and contemplating the divine mysteries of the death and passion of Christ Our Redeemer, and those of the day’s saint and of the commemoration by our mother church.”

He endures an earthquake

“Once, he was praying in the church and the ground started to shake with such strength – and it did not have to shake much to make itself felt – that he felt as if the church was falling down on him, as the roof was making great noise: friar Matias ran outside and in the cloister he saw an Indian coming running. He asked him: Where are you going ?. The agitated man replied “Father, the earth is shaking, it feels as if the world is going to crumble, and I am coming to take refuge inside the church to be under the protection of the Saint Sacraments. The Father thought : why is this Indian whom I myself baptized yesterday, coming to church when the earth shakes to put himself under the protection of the presence of God, while I, religious and Christian forever, go out and walk in the countryside ? He blushed at that thought and took the Indian by the hand and they both went to the church, and waited for the strongest tremors while praying without worry or fear. […] He mastered the Mexican language as well as the Guatemalan language, and when he was already old, he undertook to study the Mameyes language with great assiduity.”

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, Historía de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 11, chapter 5, translated by Chantal Burns)

An hospital founded in the XVIIth century, the Hospital San Juan de Dios, in Mérida, Yucatán (virtual reconstruction)

“Realizing that the poor Indians and Spaniards suffered from endemic diseases in these regions, the Conquistadores and the first settlers took pity on them and wanted to give them shelter in Mérida by building a hospital, eighty years ago or more, while I am writing this. My book explains how it was built, under the patronage of the King, how its upkeep was the responsibility of the town, and how it was entrusted to the priests of Saint John of God. Its church has only one nave, built by masons ; it is dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary. […] It has also been a convent since the year 1625.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, Historía de Yucatán, book IV, chapter XIV, Del Hospital de San Juan de Dios; de nuestro convento de la Mejorada, y otras hermitas.)

Merida, chapel of the former Hospital San Juan de Dios, today (2024, March)

Another testimony regarding the disastrous epidemics in the XVIth century, in Chiapas this time, in a village near Ciudad Real (San Cristobal de Las Casas):

The Dominicans come to the help of the sick Indians

“A serious pestilence [of smallpox] broke out in May of that year [1565] in Cinacantlán, and quickly spreading, claimed the lives of one half of all inhabitants. It caused more damages to women, children and young people. Many men died, although not as many; nevertheless those who died were the most important of the village. The most noble, the wealthiest, and the most skilled, and among them all the musicians of the church; and only fifty persons escaped death and remained in the village. At first, they helped one another, until they all got sick. Then, they suffered from tremendous hunger since there was no one to feed them, although most of them owned chickens, corn and had money. In the convent many dishes of mutton and chicken were prepared. Bread was brought from outside, and everything was distributed in the village. In the Fathers’ homes, a big pot of food was prepared for the neediest, and bread and canned food was distributed to them, some made there and others brought from the town, and it was not enough for the numerous sick people, since some houses sheltered eight diseased people and others even more.

Guatemala City, the Hospital General San Juan de Dios (2023)

They assist them in death

“Almost everyone in the convent of Ciudad Real came running to confession or for burials. The provincial Father friar Tomás de la Torre was called, and he came soon after with the prior and they worked day and night, going from one house to the next, and when they went back to the convent to tend to the convent’s affairs, they sent other diligent fathers and lay brothers who were very useful to the convent. They worked in pairs, sometime two sometime four, listening to confessions all day long and they ate quickly their meals in order to go back to that saintly occupation. And the fact that friar Juan Bautista and brother Alonso de San Isidro were able to carry out so much work since the beginning of the plague and until it ended, never leaving that place, was considered a miracle. Men were chosen to bring the sick to confession, others to carry the dead, leaving them at the door of the church with no song, no ringing of bells so as not to sadden the sick people, and they buried them twice a day in two big graves. Excluding the numerous sick people who quickly lost the ability to speak because of the seriousness of the disease, it is certain that not one person still able to think tired of confessing, and many of them with as much devotion and as many tears as if they had been dealing for a long time with affairs of the spirit.”

(Friar Antonio de Remesal, Historía de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala, book 10, chapter 18, translated by Chantal Burns)

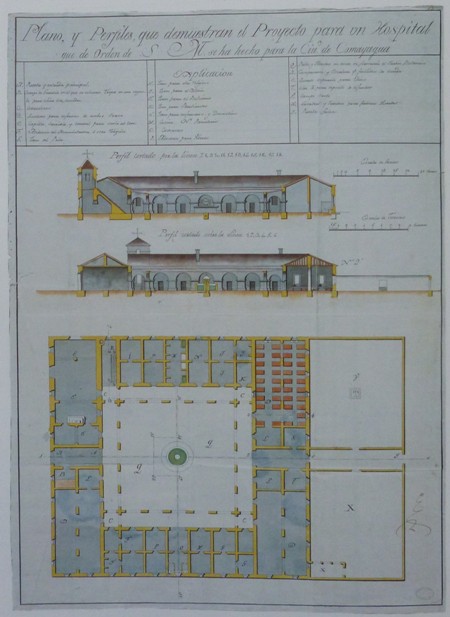

Draught of Hospital of San Juan de Dios at Comayagua, Honduras, realized by Juan de Ampudia y Valdéz, 1783, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla

Francisco Hernandez

: "On the Illness in New Spain in the Year 1576, called Cocoliztli by the Indians"

"The fevers were contagious, burning, and continuous,entirely pestilential, and in a great many cases, lethal. The tongue dried out and turned black. Intense thirst, sea-greenurine, or vegetable green and black, but from time to time the color would change from deep green to pale. Frequent and rapid pulse, but faint and weak, sometimes almost none.The eyes, and the whole body, yellow. Delirium and convulsion were reported. Behind one or both ears a hard, painful swelling appeared, accompanied by pain in the heart, chest, and stomach, shivering, distress, and dysentery; the blood, obtained by venesection, was green or very pale, dry, and completely lacking any serosity. In some people, gangrene invaded the lips, the pudenda, and other putrefied parts of the body, and blood ran from the ears; in many cases blood ran from the nose as well. Almost nobody who suffered a relapse could be saved. Many who suffered nose bleeds (provided the bleeding could be stopped) were saved, but the rest died. Those suffering from attacks of dysentery (if it happened that they were treated by medication) for the most part were normally saved, and even the abscesses behind the ears were not fatal, if they went down a bit, except when they grew spontaneously, or were drained by cauterizing with needles, and even in immature abscesses the liquid part of the blood flowed out, or the pus was eliminated, which meant also that the cause of the illness."

The entrance of the former Hospital privado Hermano Pedro, at Antigua Guatemala

Testimony of Antonio de Fuentes y Guzman regarding the organization of medicine in Antigua Guatemala in the XVIIth century

“In several places in town, there are six hospitals that were established in an exemplary and admirable way: the three hospitals managed by the keen sons of Saint-John of God, father of the poor, the Royal hospital of Saint James, the main one, that of Saint Lazarus, extra muros, where are treated those suffering from the same disease, and that of Saint Alejo, created to be exclusively dedicated to the Indians from the valley and the sick Indians from the provinces. This hospital is very useful for these people who are so destitute and poor and who, were they not given treatment or help, would die because of such poverty rather than of their serious disease and suffering.

"Of the three other hospitals, the first one is that of the famous brotherhood of the founding apostle of Saint Peter’s church, dedicated to help and treat the clerics, priests, deacons and sub-deacons who are poor, its brothers, and the two other churches are dedicated to convalescing people, one for men and the other for women, under the church of Our Lady.of Mercy: one hospital is a remarkable masterpiece, due to the simplicity of its admirable building and the extraordinary adornment of its magnificent church, refined and extravagant, as well as to the fine elegance of its lush blooming gardens and the fertility and dazzling perfection of its marvelous orchards. […]

In order to treat and ease the suffering of the sick men, our town has three public pharmacies and two other private ones established in two convents of the priests, they distribute for free a great quantity of simple and mixed products. Every year, they devote a great amount of money to them, in pesos, excluding the weekly generous alms, both in money and medications, given by the pharmacy of the convent of Our Lord Saint Dominique; both these grants are a great help to the poor.”

(Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán (1643-1700), Historía de Guatemala o recordación florida, discurso historial, demostración natural, material, militar y politica del Reyno de Goathemala, translated by Chantal Burns)

Bélen ( Bethlehem) Convalescents Hospital founded by Friar Pedro at Antigua Guatemala. Source D Fondo, 2015

A Franciscan nurse, Gaspar de Molina, in the Yucatán:

“There was another lay friar, named Friar Gaspar de Molina, who left the province of the Angels in Spain, to come to the Yucatán; he was a nurse over there and remained a nurse here during a period of more than sixty years. He was an excellent pharmacist and had such a good knowledge of diseases that he practiced medicine quite successfully. What made him so skilled in that field was the fact that he was very charitable with the sick people, so much so that he never ventured far from his infirmary, for fear of an emergency, even at night. It was very easy for him as this saintly man was naturally keen to help and treat the sick at any hour of the day. To help them better, he put a shirt on them, covered them only with a cow skin and a leather cushion and he remained near the sick person who needed him the most. And as soon as he heard a moan, he ran near the person in question. He never had his own cell; on the one hand he had no other clothes than the ones he wore and did not change, and on the other hand the pharmacy and the infirmary were his abode and he lived in one or the other according to the needs. His faith and his virtue were well known and admired by all and I can say without any flattery that he was a saint.”

(Bernardo de Lizana, Historía de Yucatán, devocionario de Nuestra Señora de Izamal y conquista espiritual, Part II, chapter XIV, of three lay friars, very saintly men of our province, translated by Chantal Burns)

Guatemala City, 2022, March, in front of the Department of Health, staff of hospitals protests for their wages

In 1648, a new disease devastated Yucatan. This was yellow fever, which had previously been absent from America

. Here is the account of the epidemic by Friar Diego López de Cogolludo:

"Pestilences are accustomed to be a common accident in other lands, which uniformly attack all, but it was not thus in Yucatan, which was the occasion of the greater confusion. It is not possible to say what was this malady, because the physicians did not recognize it.

"The most common was for the patients to be taken with a very severe and intense pain in the head and of all of the bones of the body, so violent that it appeared to dislocate them or to squeeze them as in a press. In a little while after the pain a most vehement fever, which to most occasioned delirium, although to some not. Followed some vomitings as of putrefied blood and of these very few remained alive. To others there was a flow from the bowels of a bilious humor which" (being) corrupted caused dysentery, which they call 'sin vomitos'. Others were provoked to them (vomitings) with great violence, but in vain, and many suffered the calentura and pain in the bones without other accidents.

"To the most the fever appeared to remit entirely on the third day; and they said that already they felt no pain; the delirium ceased, conversing sensibly, but they were not able to eat nor to drink anything and thus going on one or more days, speaking and saying that they were well, they died. There were many who did not pass the third day, the most died beginning the fifth, very few reached the seventh, except those who survived, and of these the most were elderly. It attacked young men, the most robust and healthy with most violence and finished their lives the quickest."

Diego López de Cogolludo, Historia de Yucathan (1688, lib. xii, cap. 12, et seq.)

The "Centro de Investigaciones Hidayo Noguchi" in Mérida. Here, in Yucatán, the Yellow fever virus was identified by Noguchi in 1919

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

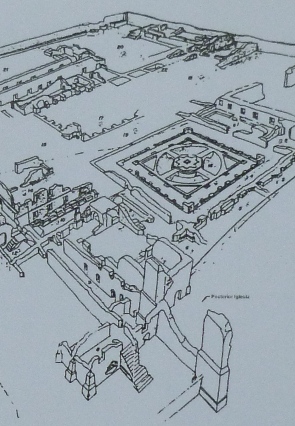

Remains of the Dominican convent in Antigua Guatemala (today Hotel Casa Santo Domingo and Centro cultural Santo Domingo)

The Santo Domingo Monastery, built in 1543 by the Dominican Friars, was totally destroyed in 1773 by an earthquake. Its rubble was used as build material throughout the XIXth century. In 1989 the ruins was dug out and the Hotel Casa Santo Domingo was built in the same area.

A courtyard of the hotel Casa Santo Domingo, in Antigua Guatemala

This beautiful hotel has been skillfully incorporated into the ruins of the dominican monastery. Several museums are housed within the same complex. In colonial days, Santo Domingo was the largest monastery in the city, center of the Dominican Province of San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala

Dominican dress ; Centro cultural Santo Domingo, Antigua (Guatemala)

Vidas Ejemplares, El hermano Pedro de Betancourt, Novaro, Mexico, 1958. Saint Brother Pedro, Fray Pedro de Betancur (1626-1667) did a great job of helping others, like lepers, prisoners, slaves and Indians. He opened Our Lady of Bethlehem, a hospital for the convalescent poor. He was a man ahead of his time, both in its methods for teaching reading and writing to illiterate and in the treatment of patients.