Multiples adventures

Dominicans and Franciscans in Maya land - XVIth century

A trip by Las Casas to Tabasco and Chiapas

Pedro de Barrientos in Chiapa de Corzo

Las Casas against the conquistadores

Fuensalida and Orbita, explorers

Numerous studies

An ethnologist friar, Diego de Landa

Two teachers, Juan de Herrera and Juan de Coronel

Two historian friars, Cogolludo and Remesal

A multitude of buildings

A Franciscan turned architect: Friar Juan de Mérida

The Valladolid convent in the Yucatán

The Izamal convent and its miracles

In the Yucatán, a church in every village

A Dominican nurse, Matías de Paz

A difficult task: evangelization

The creation of the monastery of San Cristóbal

The Dominican province of Saint-Vincent

An authoritarian evangelization

Franciscans and the Maya religion

The failure of the Franciscans in Sacalum, the Yucatán

Domingo de Vico, Dominican martyr

The end of the adventure

Additional information

The Historia Eclesiástica Indiana of Mendieta

The road of Dominican evangelization in Guatemala

The convent of Ticul, as seen by John Lloyd Stephens

The Franciscans in the Colca valley in Peru

The convent route of the Yucatán in the XVIth century

The dominican mission of Copanaguastla, Chiapas

Available upon request: -

general information upon Maya countries, - numbered texts

on the conquest and colonization

of Maya countries

Address all correspondence to:

moines.mayas@free.fr

|

FRANCISCANS AND THE MAYA RELIGION

|

The Franciscans set up to supervise every minute of the Maya population’s life in the Yucatán in order to convert them. They had a hard time to overcome the sometimes open, but most often hidden resistance of the old religion. Diego López de Cogolludo wrote the story of such an opposition at that time. A French historian of the XXth century, Robert Ricard, confirms it in his “Spiritual conquest of Mexico”, excerpts of which follow.

Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico: An Essay on the Apostolate and the Evangelizing Methods of the Mendicant Orders in New Spain, 1523-1572, translated by Lesley Byrd Simpson. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1992.

Robert Ricard’s study of the early Mexican missions is a classical interpretation of the subject. It first appeared in French in 1933 as Volume XX of the “Travaux et Mémoires de l’Institut d’Ethnologie” of the University of Paris, with the title "La conquête spirituelle du Mexique. Essai sur l’apostolat et les méthodes missionnaires des Ordres Mendiants en Nouvelle-Espagne de 1523-24 à 1572". In 1947 it was published in a Spanish translation by Ángel María Garibay K., with a special preface by the author.

Franciscans built their churches above Maya temples

The religious, for the purpose of disorganizing and overthrowing pre-conquest paganism, installed themselves preferably in built-up areas which were at the same time political and religious centers. These religious centers necessarily included one or several teocallis, or sanctuaries on the summit of pyramids, and it seemed most opportune to build churches and convents on these same pyramids, a choice which completed the political disorganization and initiated a policy of substitution.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual conquest of Mexico, book II, chapter III, 1933)

“At the time of their paganism, the inhabitants of this land [the Yucatán] usually built the temples for their idols on high ground, as indicated in book four, and since the demon pushed the people of Israel to practice idolatry in high places rather than in the plains, it seems that he fooled the Indians in the same way by comparing them to the Jews when accomplishing such rites and ceremonies. The greater part of this country being perfectly flat, the demon seized the opportunity to demand from them many great efforts to serve him, as they had to build these elevated grounds with their own hands, by moving together soil and stones with which they made a hill on which the temple was built. There were several of them in the place where Mérida now stands, and the Adelantado (Francisco de Montero) had chosen the biggest one, near the town which it dominated, to build a castle and a fortified residence with the remains of two temples which he had destroyed when he came to conquer this region ; but the divine providence intended to use it as the spiritual fortress of the faithful where to erect a temple in honour of the Divine Majesty and in which would be sung praises to the divinity. The father commissary asked him to grant him this site in order to build a convent, and the Adelantado agreed without hesitation; taking into account his devotion, he considered that the prayers of the saintly apostolic men who were to live in it would provide the most secure place. But he lost the grace and the permanent annuity that had been granted to his successors, since he did not have another location where to build the castle and since he had not built it, as had been agreed.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book five, chapter V)

Acanceh, Yucatán, the Maya pyramid, the chapel and the parish church

The Indians must learn catechism

In the convent villages the catechism was held on Sundays and feast days. Early in the morning the monitors (merinos) of each quarter of the large towns, and the alcaldes of the villages, summoned their people. Each quarter or each village assembled at the church, bearing crosses and reciting prayers. [...] Generally, they were all assembled in the square (atrio) that surrounded the church, and groups were formed around the crosses (which can still be seen in some places), the men and women were carefully separated and obliged to repeat aloud a part of the catechism two or three times, after which the sermon was preached and Mass said.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, book I, chapter V, 1933)

“We also make sure that on Indian holy days, the whole village is assembled and recites the entire Christian doctrine and the catechism, as they present the mysteries of our saintly catholic faith and their explanation in the mother tongue of the country, so that they memorize them forever and are aware of what they must believe to be saved. The work of the first priests, accomplished with saintly zeal, was to translate them in the Indian language, and our counterparts have improved and printed it to allow the Indians to read it. On a holy day, they proceed as follows: the signal is given early by ringing the big bell, and the inhabitants, men and women, come to church. When they come inside, the men are placed on the side where the Gospel is read and the women on the side of the epistle, and after having said a prayer to the Most Saintly Sacrament, they sit down on the floor and the persons responsible sit on the benches reserved for them. Once everyone is assembled together, two sextons appear, their red habits covered with a surplice, and standing near the entrance of the main chapel at the end of the nave, they sing the four prayers in the seventh tune, and people repeat what the sextons say. The rest of the Christian catechism is sung in plainsong and when it is finished, it is already time to sing the third of the rosary and to say mass, which is celebrated at an earlier time than in Spain or in the other cold lands, as the Indians need to go back to their regular occupations and their children are left in the homes.

"As soon as singing the catechism has begun, two tupiles (policemen of the catechism) stand at the doors of the church, a whip in their hands, and warn those who are late by striking them as they enter and thus show them how lazy they have been in coming to such a saintly ceremony. Catechism is said again in the afternoon in the same manner, beginning at around two o’clock when the bell rings, and the governors, the mayors and other authorities attend. Nevertheless, at that time, more women than men come; it is not compulsory for them all to come and they are not being counted, as is done is the morning. During the week, a few Indian women from the tribes are asked to come daily, each in turn, so that their presence is ensured during the great mass. The governor of the village, the regular mayors and most of the stewards and important persons or chuntanes (ah chun than) from the tribes rarely miss an opportunity to attend.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book four, chapter XVII)

Roberto González Goyri, a friar teacher, Edificio Municipal, Ciudad de Guatemala, 1959

Children in particular are indoctrinated

Although the Franciscans did not neglect the adults, they directed their principal effort to the instruction of children, whom they usually divided into two categories. The children of the lower class (called gente baja) were assembled every morning after Mass in the atrios of the churches and separated into groups, depending on their knowledge of the catechism, which they were taught, along with the principal prayers. And that was all. At the end of the lesson in the catechism they were sent home to work with their parents. [...] The sons of the principales, or native aristocracy, were handled differently and with particular care, for they were the future leaders of the country. These boys lived in the convents as boarders.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, 1933, book I, chapter V)

“Young plants grow easily, straight and beautiful and pleasant to look at, if the person who plants them gives them enough care and attention to grow them. The children, sons of our Indians, are the young plants of our militant church. Since their biological parents do not have the required vigilance to teach them the Christian doctrine, the evangelical ministers are responsible for their spiritual education which will beautify their spirit at the same time as their body grows, and which will allow us to reap the fruit expected from real Christians, making them agreeable to God and his faithful. If they were left to the care of their biological parents who are busy with their endless tasks and careless by nature, they could be endangered, even when it comes to their temporal education. The preachers and their spiritual masters’ zeal found a solution to this shortcoming by making all boys and girls from the villages go to church every day of the week, where they are taught prayers and Christian catechism ; this way the goal is reached without too many efforts.

“We have already said that all the villages were divided in districts. For each district, or for two of them if they are small, a tupil or policeman is appointed, and every morning at sunrise he assembles all the boys of the district younger than fourteen years and all the girls younger than twelve years (the age when the parents think of getting them married); they gather in a procession, the boys in one rank and the girls in another rank, and the tupil before them carrying a large cross high and striking up prayers in the seventh tune in a loud voice, and they all walk in the streets leading up to the church, which they enter in the same order, kneel down to worship the Most Saintly Sacrament, and remain in that position until all of them have entered the church. Then one of these tupiles (one of them is chosen ahead of time for every day of the week) opens the session while singing the prayers on the same seventh tune and all repeat them until it is time for High Mass. When a sign is made that it is time to sing the third of the rosary, they stop, while being attentive to the saintly sacrifice of mass. Once mass has ended, the priest goes out and leads back the authorities of the village and their assistants.

Punishment of the Indians for no attending church (Samuel de Champlain's narrative of a voyage to the West Indies and Mexico in the years 1599-1602) "... being brought before the priest, he asks them the reason why they did not come to the divine service, for which they allege some excuse, if they can find any; and if the excuses are not found to be true or reasonable, the said priest orders the fiscal to give the said defaulters thirty or forty blows with a stick, outside the church, and before all the people."

"Then, he usually counts the children with the help of lists (there are different lists for married people): he thus notices if someone is missing and their tupiles say whether they are sick or whether their parents retained them for work. If such is not the case, they go fetch them; when they arrive, they are whipped two or three times so that they do not miss church again, and the tupiles are reprimanded for being careless. If they do not show up right away, they are spotted thanks to the piece of string (kept when getting out of the church) that bears their name. When the priest is not available for counting them, the fiscal does it.

“In the afternoon, they do not come to church as they must help their parents, as much as it is possible for these young people to fulfill these domestic tasks; having given God the better part of the morning, they have the rest of the day to learn the practical aspect of human life, so that they may develop the spiritual being and the physical being, thanks to the care of their evangelical ministers who make sure to tend to one and the other. On Saturdays they do not come as their mothers wash their clothes. By following them since early childhood, we are able to enhance the desire of these Indians to be devoted to divine worship and their knowledge of the rules they must follow as Christians: in the clear mirror of daily catechism they can see which virtues to follow and which vices that offend Divine Majesty that they must avoid. The enthusiasm of the spiritual fathers is so great that they cannot be held responsible for the fact that the Indians do not know all the prayers and the Christian catechism: by continuing in vain, when they are adults, to try to teach them what they were taught as children, we note either their permanent incapacity (unless it is malice) or their bad temperament; in fact, they are scatterbrain and do not pay attention to what they repeat so many times. Because in addition to what has been said, we check their knowledge when they get married. And each year, at the time of confession, which is compulsory, they are also being questioned. And having been brought up in that manner, they remain not attracted by the church, by mass and by the saintly sacraments, as I said earlier. May God give them His grace and His help so that they may serve Him.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book four, chapter XVIII)

Saint Bonaventure feast (2024, July) in the church of Homún, Yucatán

Indian managers are appointed

The Franciscans were too few in number to undertake a regular and general instruction, (so they had recourse to) the aid of trustworthy natives, who assisted the friars and the civil officers at the same time. The natives, called fiscales or mandones in Spanish, had not only the duty of assembling the people and bringing them to Mass and the catechism. [...] In the pueblos de visita, that is, villages that lacked resident priests, the mandones policed the churches, kept the baptismal records, performed baptisms themselves in case of necessity, comforted the dying, buried the dead, and announced feasts, vigils, and fasts, and so forth.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, book I, chapter V, 1933)

“On the first day of the year, in order to help the cacique administer justice and governing the villages, two ordinary alcaldes are appointed, as well as the required number of managers and the local procurer, whom the governor appoints on behalf of the king. On the same day are chosen alcaldes “of the inns” and common houses, where passengers are welcome to receive food and provisions. A fiscal person is also chosen for the church and is responsible for teaching Christian catechism to the children, and others are appointed to serve as policemen to make the children come when they are missing. Other ministers are further appointed, and holding the royal justice stick, they make sure that that the Indians clear their land, sow and grow their milpas, or seedlings: because they usually care little for that while our existence on this land depends on the care they give to the land, and if a harvest is missing, those who suffer the most from it are the miserable Indians. We know from experience that they are nonchalant and are not friends of work, and even where their food is concerned, they must be pushed to sow since most of them do not foresee what could happen to them as long as they can feed themselves at the present moment.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book four, chapter XVII).

Mayas musicians of Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo (2023, November)

Music contributes to the solemnity of offices

The ceremonies were almost always accompanied by singing and music. The Indians generally chanted plain-song, sometimes to the accompaniment of the organ, sometimes of instruments. And the choir, we are told, could bear comparison with those of Spain. The orchestral part must have been very rich, and one is struck by the great variety of instruments: flutes, clarinets, cornets, trumpets (both real and bastarda), fifes, trombones, jabelas (Moroccan flutes), chirimías (the chalumeau, or ancient chalemi of France), dulzainas (similar to the chirimías), sacabuches (a kind of trombone), orlos (a kind of oboe), rabeles (or rebec, or vihuela de arco, a kind of guitar played with a bow), and finally the atabales, or drums.

For the desired sumptuousness of masses and services, it was not enough to have a great number of different instruments, but to have good performers and singers. They were easily recruited. Native Mexicans are great lovers of music, and they came from a distance to learn it.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, book II, chapter IV, 1933)

“To celebrate the divine office, there are in all the villages a set number of sextons and singers. The sextons are responsible for decorating the church and keeping it clean, and they help at the altar. Generally, they fill the church with flowers as there is a great variety of them all year long in that region. The singers contribute to the solemnity of the divine office, which must be sung, as the church wishes. It must be stressed that there is no village in Yucatán, however small, where the divine office is not celebrated with organ music and a complete choir, as music requests it. In convents they had small bassoons, pipes, trumpets and organs, which give great fervor to the praises in honour of the divine Majesty. These prayers are frequent and occur daily; the priests sing the divine office; and during the week, in the villages administered by us, the master of the chapel and half the singers start singing the four hours of the office of Our Lady at day break; then they sing the third of the day’s saint with the required solemnity, and in the afternoon they sing vespers, never missing one, even if the priest does not live near them.

“Every Saturday afternoon, we sing the Salve Regina for the mother of God with much solemnity and the participation of many people: women especially are present during this devotion as well as in the morning for the solemn mass said in song. All the Departments have fraternities of Our Lady and celebrate her holy days with solemnity. Every month (and sometimes every week) we sing mass for the members of the fraternity. Fraternities are present not only in Departments but in many visited villages, and they all celebrate the days of the very pure Conception of the Very Saintly Virgin Mary with particular devotion. There is an organ in each of our convents, a feat difficult to achieve since most of them were brought from the kingdoms of Spain and paid with the alms given to us for our subsistence and our clothes, when possible, in order to sublimate the divine worship. In the visited villages or annexes where it was impossible to set up an organ, they use instead flutes to accompany bass voices, contraltos, tenors and sopranos, and they alternate with verses of the psalms. Many others even have trumpets and pipes. It is a remarkable feat (on the part of these people who are considered barbarians and known for their simplicity), since when we compare them to the villages of our land of Spain, we note that only the churches receiving a large allowance possess an equivalent setup and that the churches of this region that do not get any income are served with such decency and ceremonial thanks to the vigilance of the priests. To ensure a continuity, there are schools near the churches, in their yard, where the chapel masters teach reading, writing and singing to some children; this way we train not only servants of the divine worship but also secretaries useful to the villages.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book four, chapter XVIII)

Friars standing around the Cruz de Evangelización, at the Calzada de los Misterios, Mexico city (monument built in 1999)

A delicate problem : translate Christian terms

In Mexico, as in every mission, there was the delicate problem of translating Christian terms in the various native tongues, terms representing things or concepts radically new to the converts. [...] Besides, would it not have been imprudent, in fact, to use for baptism, confession, and communion, native terms which were superficially analogous, but which were entirely different in meaning and scope? The precaution of Zumárraga, bishop of Mexico, is understandable, when he prohibited the use of any term that might cause confusion in the minds of the Indians, and it is understandable why religious texts in native languages are sprinkled with Spanish and Latin words, such as Dios, Apóstoles, Yglesia, Misa, Sanctus Spiritus, and so on. The Mexican mission adopted this approach for another reason, namely, the very low opinion that most religious seen to have formed of the spiritual capacities of the Indians.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, book III, chapter III, 1933)

“[Friar Luis de Villalpando] had told them [in 1547], during his sermons and among other spiritual notions that God our Lord has great love for men, and that His Divine Majesty can be compared to a hen that, when her chicks ask her to protect them, shelters them under her wings to defend them from the hawk that always tries to kidnap them and turn them into a prey he can devour. That on the spiritual plane, priests had the same role to play with men and should shelter and protect them against their enemies, the demons who by all means tried to kill them; and that consequently, they had to appeal to the priests in case of harm and misfortune in order to find real peace and the relief they needed. The Indians, who were not very smart and who at that time hardly knew the divine mysteries, took to the letter the idea of finding shelter under the protection of the priest and one of them, who had been threatened with punishment by a higher up, came to Father Villalpando and, crawling under his habit, settled there without a word. The Father did not understand why the Indian acted that way but let him do so as he did not want to hurt him by pushing him away, and thought he had a good reason for such a behavior. This happened several times and the Father wanted to know why, when once, a child happened to stand behind him and covered himself with his habit. The Father asked him why he behaved in such a way and the child answered: they want to whip me and I am putting myself under your protection since you are a forgiving father and I heard you talk about protection eight days ago. He recalled what he had preached to them and thanked the Divine Majesty when he realized how well they took to his preaching and how sweet and docile they were. Since then, when a similar event occurred, he told them not to bother the one who came to seek his protection, for it was just for him, the father of their soul and the priest of Christ to be a refuge for the sinners and those who made mistakes, so much so that the love of the Indians and their respect for their spiritual father grew and they did whatever he requested them to do without any reluctance.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book five, chapter V)

Rebeliones indígenas de la época colonial, recopiladas por María Teresa Huerta y Patricia Palacios, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México, 1976

A rebellion against Catholicism in the Yucatan

Evangelization encountered many obstacles among the natives. The peoples of the coast, the Anahuac plateau, and Michoacán did not violently oppose the coming of the missionaries or the preaching of the Christian faith. […] In other regions, the rebellion of the Indians had a very different meaning and extent, because it was a general movement and brought in a large number of tribes. It barely failed to put an end to the European occupation. There is no doubt whatever of the religious nature of this uprising. The insurgents were fighting, not merely for their liberty, but for their religion; they were fighting, not merely against Spain, but against Catholicism.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, Book V, chapter II, 1933)

“They hid their bad intention until the day when, on the ninth of November 1546, the revolt erupted in several places, as they had planned it in order to succeed in their endeavours. The first ones to be caught in such an avalanche of misfortunes were two Spanish brothers, Juan Cansino and Diego Cansino, legitimate sons of Diego Cansino who was one of the conquerors of New Spain, and of Magdalena de Cabrera. Both were in the village of Chemax, having no clue that the Indians were preparing a big surprise for them. A great many of them assaulted them and they had no arms to defend themselves, they had to surrender immediately. The hatred they had for the Spaniards can be measured by the slow death they inflicted on these two young men (a forbearer of their vengeance); they did not kill them immediately as they would have done in a fit of rage, but tortured them terribly all day, which undoubtedly proves their cruelty. They had set up two crosses on which they attached them; and moving further away from them they used their bows and arrows on the two crucified young men, the object of their revolt, covering them with arrows. The victims realized that the main hatred of the Indians came from the change of religion and customs that had been imposed on them and by forbidding them to publicly worship their idols, and from the crosses they told them to come back to the promise they had made to submit to the king and the church. The only answer they heard was blasphemy and hatred for the king and total disdain for the church.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book five, chapter II)

Mayas continue to practice their religion

The survival of paganism in Mexico seems to be undeniable. Certain native groups, protected by their isolation, have not yet given it up and still venerate their ancient idols and hardly have the idea of a supreme God, whom they represent, moreover, as a material being. [...] They have many sorcerers, who are greatly feared, among whom the parish priest occupies only an inferior rank. They receive the sacraments, but still celebrate rites that are pagan in form and substance. They do not recognize baptism, they do not attend Mass, and they continue to worship their idols, which rest in their hearths in the company of a few images of Christian saints. [...] The Indians had seemingly renounced to idolatry, but continued to practice secretly at night, worshiping their gods and offering sacrifices. […] Sometimes, the idolaters gathered in caves of difficult access, there to continue their cult; at other times, with a refinement of dissimulation and an excess of caution, they hid their idols behind the crosses, or below the altars of the churches.

(Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, 1933, book III, chapter II)

Franciscans opposed to human sacrifices (palacio de gobierno, Valladolid)

“Reaching a village today called Zitaz [Dzit Haaz] located on the land of the Cupúles, [Diego de Landa] got tired after walking on foot in such a hot region and he thought of finding lodging in the house of the cacique of the village. The house opened on the plaza and when he reached it, he saw that it was entirely decorated and ornate in the traditional way, very well prepared for a solemn sacrifice in favour of their idols. There were several big vases filled with a drink that made them drunk during the sacrifice, and another vase full of a drink that made the victim lose consciousness and fall asleep, so much so that he did not fight when his chest was cut open and his heart torn out and used to sprinkle with blood their idols in honour of which such an inhuman act was being performed. They were getting ready to perform the sacrifice on a young man of about eighteen years of age, who was covered with flowers and tied to a pole. Father Landa, showing no fear and saying nothing to the Indians, went near the pole where the miserable young man was tied and freed him, and stood beside him. He pushed the idols to the ground, broke the vases containing this idolatrous drink and, inspired by God, told them to listen to what he had to teach them for the good of their souls.

“There were more than 300 Indians present at this ceremony, and in the circumstances, pushed by the demon, they usually would become as furious as lions; this time, they did nothing except look at each other, astonished but calm, which was unusual, and listened to what the apostolic saintly man had to say. Seeing they were quiet, he gave them a big speech and told them that they had to entirely know, love, fear and worship only one true God, infinite and all powerful, creator of all things, and rewarding the good people and punishing the idol worshippers and the sinners. He said that His Divine Justice would be a great threat for them in case this innocent young man whom they unfairly wanted to kill died. They had to know that his majesty had sent him to them so that they do not commit such an evil act and to make sure that this young man, while dying a temporal death because of them, would not die an eternal death without being a Christian. He showed them the goodness of God our Lord, who grants his friendship to the repented sinner, and the cruelty of the demon which they adored through the idols. That only God was the master of life and that it could be proven only in situations allowed by the saintly faith: that it was glorious to offer one’s life in favour of one’s faith and totally disgraceful to offer it to the demon. That the Eternal Father had sent His only son to the world as a man, pushed by infinite charity, so that he would redeem us by dying, thus giving us eternal life. That only the god he talked about could grant life in the other world and the temporal life we had at present in this world. That their fake gods could not give it or take it and that the demon pushed them to suppress each other’s life to take them faster to hell, so that they would endure eternal torments in his company.

"After all these truths were spread around, God shook the hearts of these idol worshippers who became distressed and asked him to take the time to teach them what they had just heard, as they wished to learn, and to prove it they themselves smashed the idols in his presence. Acquiescing to the wish of the Indians and in his desire to see them become Christians, he remained with them to teach them catechism and to train them, going all over the territory until he was called by obedience at the beginning of the year fifty-one. The Indians later said that the reason why they had remained so quiet when he had set the young man free and smashed the idols was because of the terror they had felt when seeing the great bright light shining on his face while he was talking to them.”

(Diego López de Cogolludo, History of the Yucatán, book five, chapter XIV, translated by Chantal Burns)

Dzitas, Yucatan, turkey dance, Kots kaal tso fiesta, January 16 through January 22. This prehispanic fiesta is now in honor of Santa Inés (2024, January).

2025 "Friars and Mayas"

|

San Luis Obispo church, in Calkini (Campeche). The convent was built on top of a Maya platform.

"The convent is finished, with its upper and lower cloister, dormitory and cells, [...] and all of it is situated on a ku or mul of the ancients." Antonio de Ciudad Real, Tratado curioso y docto de la grandezas de la Nueva España, capítulo CXLIX, De cómo el padre comisario prosiguió la visita y llegó a Calkini, 1588

Procesion at Tehuacan, Mural in Museo de Peñafiel y la Fuente de El Chorrito, paint by Desiderio Hdz. Xochitiotzin

Catechism by father Jerónimo Martínez de Ripalda. It was used for many centuries to teach Christian doctrine, Spanish language, good citizenship and reading. It was translated into náhuatl, otomí, tarasc, zapotec and maya.

C-YUM

Our Father

C-YUM YANECH TEJ CAANO

Our Father who art in heaven,

QUILIICHCUNTAAC A KABÁ,

hallowed be thy name.

TALAC TOON A AJAWIL

Thy kingdom come.

BETAAC A WOLAJ JE BISH TEJ CAANÓ

Thy will be done

BEY SHAN TI LE LUUMÁ

on earth as it is in heaven.

DZA TOON BEJELAE' U WAJIL SAN SAMAL

Give us this day our daily bread,

SAATES TOON C-P'ASHOOB JEBISH SHAN

and forgive us our trespasses,

TOON C-SAASIC LE C-AJ-P'ASHOOB

as we forgive those who trespass

against us,

YETEL MA A P'ATIC C-LUBUL TI TONTAJ-OL,

and lead us not into temptation,

BAALÉ TOCOON TI TULACAL KAS;

but deliver us from evil.

TUMEN ATI'AL LE AJAWILÓ YETEL LE PAJTALILÓ

For thine is the kingdom,

YETEL LE NOJBEENILO UTIAL JAABOOB

and the power, and the glory,

MINAAN U SHUL.

for ever and ever.

CA BEYAC.

Amen.

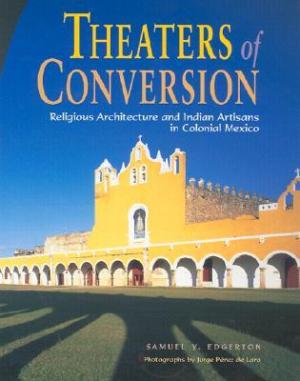

Samuel Y. Edgerton, Theaters of conversion, Religious architecture and Indians artisans in colonial Mexico, University of New Mexico Press, 2001

Indian cantors (Oaxaca, mural at palacio de gobierno, painted in 1980 by Arturo García Bustos)

An ambiguous symbol for the Indians: the Holy Trinity (cathedral of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala)

The church of Saint Anthony of Padua in Chemax, Yucatán, built in XVIIth century